"It is only necessary to remember the solitary main rule:-- 'Nothing is to be done contrary to what could or would be done in real war.'" (Jane, 14)

This admonition of Fred T. Jane in his 1912 edition of "How to Play the Naval War Game" always makes me smile. I can't imagine many games finishing without argument if that was really the only rule players had to work with! Of course, Jane does provide a lot more material in his book for the beginning naval wargamer to work with. And, as we'll see, this book, published shortly before Wells' "Little Wars," began a pattern in Seekriegspiel's publication history similar to what the latter did for land based wargaming.

Jane's introductory remarks are as interesting as the rules themselves, at least from the wargaming historian's point-of-view. He reflects on the development of the rules over a 13 year period, and one can see that he struggled with many of the same questions we continue to deal with in 21st century wargaming. Since he was dealing with contemporary warfare, he had to continually adjust to technological changes, but the most critical development was a movement towards simplicity. He'd found that a collection of detailed rules and regulations led to a "general standard of uniformity" (7), but came to realize that this uniformity had little to do with real war. By creating a result set known to the players, the wargamers had much more information than they would in the real world. A way had to be found to reintroduce the fog of war.

Two methods served to simplify the game for the players and to partially blind them to what was going on at the other end of their ammunitions' trajectories: Heavy use of umpires and a Striker and Target system for producing hits on enemy vessels. The umpire's role is critical in Jane's game, reminding me a bit of the gamemaster's place in role-playing scenarios, whose godlike perspective and decisions have much to do with the flavor of a particular game. Of course, Jane's umpires were restricted by the "main rule" cited above and the specific mechanics defined in the rules (though they could even change those before a game began!), but their decisions were law and they had wide latitude within that prime directive and its corollaries to punish inappropriate or unrealistic acts by the players. For example, communication between Admiral and Captain, other than by signaling as defined in the rules, regarding tactics and damage was forbidden with a complete machinery breakdown as the penalty for any conversation! During the game, the Umpire could not be questioned, but was expected to describe his decisions afterwards, particularly in cases that were controversial.

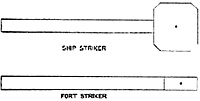

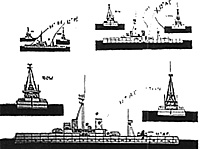

The Striker and Target system took over from result charts and dice by giving players a physical tool which actually produced "hits" on targets representing the target vessels. Designed with off-center pins, in different locations on each, the striker gave the attacker a best guess opportunity to hit a specific ship's target which also varied in size according to the range. This system introduced a bit of chance and luck into the firing process which Jane felt was critical to a realistic simulation of naval warfare. This element was enhanced further for the players since the actual damage produced by their hits was determined by the umpires. Obviously the game depended on umpires with a certain level of knowledge to judge "realistic" outcomes, but the latitude they possessed added to the lifelike effect Jane was searching for.

The Striker and Target system took over from result charts and dice by giving players a physical tool which actually produced "hits" on targets representing the target vessels. Designed with off-center pins, in different locations on each, the striker gave the attacker a best guess opportunity to hit a specific ship's target which also varied in size according to the range. This system introduced a bit of chance and luck into the firing process which Jane felt was critical to a realistic simulation of naval warfare. This element was enhanced further for the players since the actual damage produced by their hits was determined by the umpires. Obviously the game depended on umpires with a certain level of knowledge to judge "realistic" outcomes, but the latitude they possessed added to the lifelike effect Jane was searching for.

These two factors allow for an otherwise fairly simple game system: Fire and movement are quickly learned by beginning players, and the broader elements need for campaigns and wars are clearly set out. Provision is made for resupplying ships -- no endless supplies of coal, or infinite ammunition in the armory here-- as well as signaling, mines, night fighting, operations against land fortifications, submarines and aerial operations. Appendices include specification tables to aid umpires in determining results of shooting, and turning circles to aid players in accurately moving their ships.

Jane's rules are a bit closer to military training tools in their intent than the other games this series has reviewed, but the next rule set brings us back to our main focus of wargaming as a hobby. Fletcher Pratt's "Naval War Game" first appeared in 1940 and proved a popular pastime during World War II for many in his circle who remained in the States. It was realistic enough to predict the outcome of the Graf Spee's fight off the South American coast, though the players in the game which anticipated the event had supposed that their result was a freak occurrence!

Jane's rules are a bit closer to military training tools in their intent than the other games this series has reviewed, but the next rule set brings us back to our main focus of wargaming as a hobby. Fletcher Pratt's "Naval War Game" first appeared in 1940 and proved a popular pastime during World War II for many in his circle who remained in the States. It was realistic enough to predict the outcome of the Graf Spee's fight off the South American coast, though the players in the game which anticipated the event had supposed that their result was a freak occurrence!

Like Jane, Pratt depends on referees to carry out some of the actions in the game, and to punish "captains" who stray from its rules and spirit. On the other hand, Pratt uses a point system, something Jane had rejected, for defining the initial value of each vessel and determining the effects of battle activity. The formula for this value is (9):

- Value=(Gc(squared) X GN + Gc'(squared) X Gn' + 10TT + 10A(Squared) +

10A'(squared) + 10A" + 25Ap + M)Sf; + T

Ugh! At least that was my first reaction! Of course it isn't all that difficult an equation once you know that Gc and Gc' represent the caliber's of the main and secondary batteries, and Gn and Gn' their respective numbers; TT, the number of torpedo tubes; A, A' and A", belt, turret and deck armor thickness; AP, number of airplanes; M, number of mines on board; Sf, speed factor; T, standard displacement. Actually, once you've found the data and done the calculation, the game is pretty straight forward! As damage is assessed, points are deducted which gradually cuts back the combat effectiveness of the ship. Accumulated damage reduces the speed of the vessel, cuts back her firepower, and, finally, sinks her.

Other than ship models and ship-cards listing the point scales, a couple of other tools are necessary to play Pratt's game. Speed-scales are marked in knots to provide a measuring device for movement, and must be flexible to ease turning movements. Their size varies depending on the scale of the space available. In Pratt's own situation, the normal playing space was an eighteen foot square dining room floor, but ballrooms were rented to permit dozens of people to play and gymnasiums are mentioned as an option, so there seems to be no upward limit to the amount of space that could be used. At the other end of the scale, ping pong tables are suggested as possible playing surfaces, so it's easy to see why a variety of measuring devices would be handy to have around.

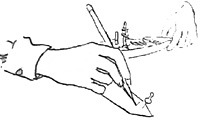

The final tool for the basic naval game is the Firing Arrow. These are used to aim shell fire and provide a place for the firing player to estimate the distance to the target. Since this estimate is actually used in determining the fire's effect, we see that this is Pratt's equivalent of the Striker and Target system used by Jane. It introduces a chance and skill factor which, especially in larger scale affairs could produce varying results. Because the movement and targeting sequences also operate under fairly strict time controls, these estimates have to be made in a "real time" situation, adding more room for error, and realism. It's interesting that artists were considered prime recruits for the game as their skills often gave them a good eye for judging distances. I'm afraid that my own performance would be less than adequate, as my ability to estimate distances on the gaming table is about as successful as my ability to roll a "6" in DBA.

The final tool for the basic naval game is the Firing Arrow. These are used to aim shell fire and provide a place for the firing player to estimate the distance to the target. Since this estimate is actually used in determining the fire's effect, we see that this is Pratt's equivalent of the Striker and Target system used by Jane. It introduces a chance and skill factor which, especially in larger scale affairs could produce varying results. Because the movement and targeting sequences also operate under fairly strict time controls, these estimates have to be made in a "real time" situation, adding more room for error, and realism. It's interesting that artists were considered prime recruits for the game as their skills often gave them a good eye for judging distances. I'm afraid that my own performance would be less than adequate, as my ability to estimate distances on the gaming table is about as successful as my ability to roll a "6" in DBA.

While referees are somewhat less important here than the umpires in Jane's game, we are constantly reminded of their role in the Notes to each Rule. Pratt notes, for instance, that movement is the most likely occasion for "rule-beating efforts that can be halted only by stiff penalties." (16) He's fairly specific in the penalties to be assigned by the referees, but allows them some latitude for improvisation. One case involves turning movements where the rules limit turning to ninety degrees. The "penalty for turning too sharply -- a steering-gear breakdown ... with a requirement that the ship continue to turn circles for at least three moves more." (16)

Movement is quite simple, determined by the speed-scales and damage adjusted ship-cards. Shooting is also simple enough, as already described. After the direction and range are noted on the firing arrows, and the players have left the playing area, or the room (it seems that arguing the point was as entertaining 60 years ago as it is today), the referees lay out the actual points where shells landed. The first impact point is the one noted by the firing arrow; the rest of a salvo normally falls at one inch intervals closer to the firing vessel, though the firing player may define this more specifically if desired. Damage is assessed for each target vessel using a penetration table provided in the rules, and the ship-cards are updated to reflect this. Markers note the impact points, so players can see how well their estimates worked out. And play moves on.

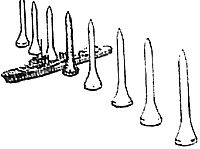

Pratt also makes provision for torpedoes, and submarines, and, coming along 30 years after Jane wrote, aircraft play a much larger role in this game. Another tool is necessary for using aircraft. For each squadron, or individual plane, if one wishes, a dowel marked in elevations and based so that it will stand vertically must be prepared. Strings of appropriate length are attached to the base of the dowel to measure horizontal movement. (Rulers are not used here in order to inhibit measurement for purposes where estimates are the rule.) Movement is affected by climbing and provision is made for rearming of planes. There are rules for airplanes against ships and vice versa and for airplanes against airplanes. The basic firing mechanisms reflect the ship to ship fire that players are already familiar with. The mechanics are simple enough but, "Handling airplanes in the game is a complex and difficult business, a headache all the way. The only comfort players can take is that it seems to be just as much of a headache in actual warfare, whether for the people that handle them or have to fight against them."

Pratt also makes provision for torpedoes, and submarines, and, coming along 30 years after Jane wrote, aircraft play a much larger role in this game. Another tool is necessary for using aircraft. For each squadron, or individual plane, if one wishes, a dowel marked in elevations and based so that it will stand vertically must be prepared. Strings of appropriate length are attached to the base of the dowel to measure horizontal movement. (Rulers are not used here in order to inhibit measurement for purposes where estimates are the rule.) Movement is affected by climbing and provision is made for rearming of planes. There are rules for airplanes against ships and vice versa and for airplanes against airplanes. The basic firing mechanisms reflect the ship to ship fire that players are already familiar with. The mechanics are simple enough but, "Handling airplanes in the game is a complex and difficult business, a headache all the way. The only comfort players can take is that it seems to be just as much of a headache in actual warfare, whether for the people that handle them or have to fight against them."

While there are differences in detail and approach, Pratt's rules differ from Jane's mostly in their goals. The later rules are definitely a hobbyist's game, though care was obviously taken to reflect real world sea warfare. Jane's rules appear to make an entertaining game, especially when used for smaller actions, but are designed for training for larger scale conflicts. Indeed, one of its objectives is "To afford a means of working out any strategical problems or theories with realism and excitement substituted for 'dry bones'." (Jane, 8) It's interesting that both found that using a neutral party, whether referee or umpire, added significantly to the realism and the fun of the game. Perhaps the "human element" is the critical factor in achieving a balance between realism and playability, our eternal dichotomy.

Bibliography

Jane, Fred T. How to Play the "Naval War Game." [London: Sampson, Low, Marston], 1912. Reprinted by Hemel Hempstead, UK: Bill Leeson, 1990.

"The Jane Naval War Game." Engineer. 85: 24 June 1898, 581+. Reprinted in: Featherstone, Donald. Naval War Games. London: Stanley Paul, 1965.

Pratt, Fletcher. Fletcher Pratt's Naval War Game. N.p.: Harrison-Hilton,

1943. Reprinted by Daniel J. Dorcy. Sheboygan, WI: Lakeshore Press, 1978.

More Roots of Wargaming

-

Robert Louis Stevenson

H.G. Wells

Shambattle

Children and Toy Soldiers

Links Between Military Miniature Collecting and Gaming

Jack Scruby

1962

Table Top Talk Magazine

Naval Wargames Part 1

Naval Wargames Part 2

Air Wargames

Horse and Musket I

Napoleon Rides Again

Featherstone Again

Back to The Herald 43 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com