It is often stated that Oliver Cromwell viewed the body of the King. This may well have been so, but like so many other areas, has been greatly discussed. As C.V Wedgwood states in her book on the burial of Charles I "..when history fails to supply the moment of drama, human invention will often fill the gap".

A "death-mask" of Charles I, is today on display in the armoury at Hatfield House, home of Lord Salisbury. It appears to have been shaped out of a thin sheet of metal, and it is painted a bronze colour. The features certainly resemble those of the King, but it is uncertain exactly how old the mask is. It would seem to have been omitted from all the inventories of the contents of the house, although it is certain that it has been at Hatfield since 1840, when the armoury was re-arranged. The mask peers out from inside a helmet.

If this mask is genuine, it is certainly unusual, for most surviving death-masks are of plaster or wax. Death-masks were often made, to be used for the funeral effigy of the deceased. No such effigy was made for Charles. There would appear to be no record of any impression being taken, for a death mask, although the practice was common. Oliver Cromwell's death mask, for instance, still survives.

Some days passed before the House of Commons gave the order for the King's burial. It would seem odd. The nearest suitable place was a royal vault in Henry VII's Chapel, in Westminster Abbey. Both parents of Charles are buried in this vault. Objections were made in the House, to such a famous, and readily accessible site. Parliament did not want to see Charles' tomb, a place of pilgrimage, or a place for demonstrations, on their very doorstep.

Opening the vault in Westminster Abbey, would have been a relatively easy task. As already mentioned, the internal organs were usually buried immediately after the embalming had been completed. We know that a separate canopic chest was not buried at Windsor; were they buried in Westminster Abbey, or elsewhere! Sadly, the archives of Westminster Abbey give no answer, and there are no records of any openings of a royal vault. In fact the Abbey's records have a complete gap; nothing survives covering the years 1643 to 1659 inclusive.

Parliament eventually decided that St. George's Chapel at Windsor, would be a suitable burial place for the King, and preparations were put in hand for the burial.

News of the execution spread quickly, and was reported in all the newssheets. Sadly it took the longest time to reach those who were most deeply concerned. Rumours were rife, but the Prince of Wales, in the Hague, did not receive definite news until February 4th, and Queen Henrietta Maria, in France, did not hear until February 9th.

BURIAL

As Charles had wished, the Duke of Richmond was put in charge of the funeral arrangement, the cost of which, Parliament dictated, should not amount to more than five hundred pounds. This sum was adequate, but certainly not excessive by the standards of the time. The King's body had to be moved to Windsor, and suits of mourning provided for all his servants, who still numbered nearly twenty.

The funeral was to be small and quiet, and certainly not the full state occasion which would be expected under "normal" circumstances. Charles was to be given a decent burial, but on more suited to an ordinary member of the nobility, rather than of a ruling monarch.

On February 7th, Herbert and Anthony Mildmay, with the assistance of John Joiner, conveyed the body to Windsor. The journey took place at night. Few people would have seen the procession either leave Whitehall, or arrive at Windsor. The King's coach, containing the coffin, was hung with black material, as were the four other coaches, which contained the Royal servants. Two troops of horse accompanied the coaches.

Upon arrival at Windsor, the coffin was carried from the coach to the hall of the Dean's house, also draped with black hangings, where it lay briefly before it was carried to the King's bedchamber. Richmond arrived at Windsor on the 8th, accompanied by three other noblemen, who had attended the King through the last years of the wars; Hertford, Lindsay and Southampton.

They visited St. George's Chapel, to decide on the exact place for the burial, and to make the necessary arrangements, only to discover that Colonel Whichcot, the Governor of the Castle, had already prepared a grave in the Chapel, near the tomb of Edward IV on the north side of the High Altar. This grave was rejected by the peers, who wished to lay Charles in a more prominent position, in one of the Royal Vaults, where the bones of earlier Kings were known to rest.

It had, however, been over one hundred years since any Royal burials had been made in the Chapel, and some doubts as to the whereabouts of the vaults existed. Walking up the choir, they managed to locate a vault by stamping on the pavement, and tapping it with their walking sticks, until they heard a hollow sound.

They "...caused the place to be opened, it being near to the seats, and opposite the eleventh stall on the Sovereign's side, in which were two coffins, one very large of King Henry VIII , the other of Queen Jane, his third wife, bothe covered with velvet". There was space in this vault for one more burial; originally intended for Henry's sixth wife, and surviving widow, Katherine Parr. Katherine had, however, married again, and had been buried elsewhere. Richmond checked the space in the vault, and found that it was large enough for Charles' coffin.

Whilst the vault lay open, and when the chapel lay empty, it is reported that a soldier entered the vault. He broke a hole in Henry's coffin, presumably he was looking for any items of value; he found nothing, but removed a piece of the velvet pall (a small piece which he did not think would be missed), and a piece of bone, which he stated (when caught) that he intended to make into a handle for a knife. It is not known what punishment, if any, he received.

The lead coffin of Charles, was never given an outer wooden, velvet covered coffin, as would have been expected, and it still bore no inscription. Richmond obtained a strip of soft lead, some two feet long and two inches broad, and traced out the words "KING CHARLES 1648". This strip was then soldered to the lid of the coffin. It is said that one of the noblemen present, wished to look once more, on the face of his master, and that the coffin was briefly opened before being soldered down for the last time. This story must be considered doubtful, as the opening and re-sealing of the coffin would not have been easy, or recommended, after eight days had passed since the execution.

Richmond then saw Colonel Whichcot about the funeral arrangements. Parliament had given Richmond permission to use whatever service he chose, and he intended that Bishop Juxon should read the Service For the Dead, from the Book of Common Prayer. Use of this book had been prohibited by Parliament, and Whichcot absolutely refused to allow it to be used on this occasion, despite protesta tions from Richmond. Whichcot stated that if Bishop Juxon "..had any exhortation without the book- he should have leave ......

The King's body, had, meanwhile been moved from his bedchamber, into St. George's Hall. The rough lead coffin covered by a black velvet pall, possibly the same one which was used on the scaffold.

Shortly before three in the afternoon of February 9th, a small procession set out for St. George's Chapel. The coffin was carried on the shoulders of soldiers from the Windsor garrison. The black velvet pall covered the coffin, and reached nearly to the ground on either side. The front end of the pall was turned back over the coffin, to enable the bearers at the front to see the way, and the corners of the pall were held clear of the ground by the four Lords, Richmond, Hertford, Southampton and Lindsay. Bishop Juxon followed the coffin, and carried the Book of Common Prayer, which remained closed. Then followed the rest of the King's servants, and finally Colonel Whichcot, to see that his orders were obeyed.

The King's children, Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth, although they had been allowed by Parliament to see their father before his execution, were not present at the funeral.

The cold weather had still not yet broken. As the coffin was carried from St. George's Hall, it began to snow, and it fell so fast, that by the time the short journey to the west end of the Chapel had been completed, the black velvet pall was covered by a thick layer. Much was made of this at the time; Charles had worn white satin at his Coronation in 1625, rather than the traditional purple robes, and his coffin was covered in pure white snow, the colour of innocence, when his body entered St. George's Chapel, his final rest ing place.

Bishop Juxon refused to extemporise a service at the graveside, in the Puritan manner, as Whichcot had suggested. No service was heard, no prayers were said aloud.

Bishop Juxon refused to extemporise a service at the graveside, in the Puritan manner, as Whichcot had suggested. No service was heard, no prayers were said aloud.

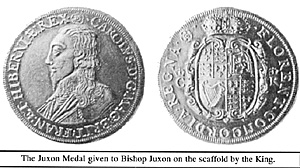

The Juxon medal the King gave Bishop Juxon while on the scaffold.

The heavy coffin was lowered in silence into the vault, a silence which would have been broken only by the muffled movements of the small group surrounding the vault entrance in the floor of the choir.

There was a moment of hesitation over the velvet pall, which Richmond indicated should remain covering the coffin, now in the darkness of the vault. The Bishop, the King's friends and Servants left the Chapel, while Whichcot remained to supervise the re-sealing of the vault, and the replacing of the paving slabs.

As Herbert was later to recall.. "So went the white King to his grave, in the forty eighth year of his age and the twenty-second year and tenth month of his reign".

RE-BURIAL

After the restoration of King Charles II, in 1660, consideration was given to the reburial of the body of Charles I, and the raising of a suitable monument. For the early years of the reign of Charles II, his fathers grave still remained unmarked. It was even asserted by some, that Charles I had been buried in secret, and in private at Whitehall, and that the coffin carried to, and buried at Windsor, was filled with bricks and rubbish.

Lord Clarendon, in his "History of the Great Rebellion", states that Charles 11 fully intended to re-bury Charles I, and "..spoke often of it, as if it were only deferred till some circumstances and ceremonies in the doing it might be adjusted". No positive action was taken, and Clarendon continues... "by degrees the discourse of it was diminished, as if it were totally laid aside upon some reason of state". He goes on to explain the reasons for no action; simply that Charles' body could not be found. He added weight to his argument, and states that after the restoration of Charles II, two of the Lords who were present at the burial of Charles I (Southampton and Lindsey), went to Windsor with their servants, who had also been with them at the time of the burial .... .. but were unable to find the spot where the King had been buried". Clarendon explains that "..the confusion they had at the time observed to be in that church, all things pulled down which distinguished between the body of the church and the quire, and the small alterations which were begun to be made towards decancy, so totally perplexed their memories that they could not satisfy themselves in what place or part of the church the Royal body was interred'. Upon their directions the ground was opened up in several places, but without success, and in the end, the project of the re-burial of Charles I, was, for the moment, abandoned. There is no reason to give any credit at all to this story, for the site of the burial was perfectly well known. Samuel Pepys, for example, was shown the spot on February 26th, 1666, when he visited St. George's Chapel.

The Chapel was damaged during the period of the Civil Wars, but in fact, it is surprising how little it did suffer. There is no evidence at all that the screen between the choir and the nave had been removed, or that the stalls in the choir had been damaged or replaced.

The real reason why plans for a re-burial were not taken up in earnest, at least during Clarendon's lifetime (he died in 1674) was Charles II's chronic lack of money, following his Parliament's failure to provide him with the income it had promised. Not being able to find the dead king's body was no doubt, a politically more sensible reason to give to the nation. The matter was not forgotten, however, and on January 30th (a significant date) 1678, the House of Commons sat in committee, with Sir Philip Warwick in the chair. This committee had been formed, to take in hand the re-burial of Charles I. Charles II had himself calculated the cost of such an exercise to be £ 80,OOO, although Secretary Williamson added, "If there be a monument, the charge will not presently begin, it will be four years in building". Secretary Coventry proposed a procession and a monument, and stated that.. "the great charge, and the wars, we have been in almost ever since the King's restoration, have hindered the King from doing it".

A long discussion followed about the most suitable site for the re-burial. St. Paul's was suggest (at that time being re-built, following the Great Fire of London in 1666); others suggested the Henry VII chapel in Westminster Abbey, but in the end it was decided to leave the final choice to "the King's pleasure". It was also decided at this meeting, that two months tax should be raised, at the rate of £ 34,000 each month. A Bill to this effect was ordered to be brought before the whole House of Commons. On February 12th, the Bill received its first and second readings in the Commons, and on March 20th, was considered in a Grand Committee.

The only speech recorded at this meeting, was that of a Mr. Waller, who stated that, "The other day I was at Windsor, and an old Sexton showed me the place where the late King was buried in St Georges Chapel". Clearly the location of the King's burial place was known (assuming of course, that the Sexton indicated the correct spot). Any remaining doubts, however, were quickly settled by Herbert, who was still alive, and in a position to identify the exact spot. He was also able to state that he had witnessed the King's body being encoffined, and laid to rest.

It may be worth noting here, that it was at this time that Herbert was persuaded to write his memoirs. These form an excellent account of the last days of Charles I, although they are, perhaps, a little too concerned with Herbert's own services to the King, and contain many errors of facts and dates. To be fair to Herbert, it must be said, that he was at this time, over seventy years of age, and he was being asked to recall events which occurred thirty years before. It is also doubtful if he had access to any Parliamentary newsheets, which would have enabled him to check details of his account.

NEW MAUSOLEUM

Charles II decided that his father's body should remain at Windsor, but that it should be re-interred in a new mausoleum, which was to be designed by Sir Christopher Wren. This mausoleum was to be built on the site of Cardinal Wolsey's Chapel, which adjoined, and formed part of St. George's Chapel. This part of St. George's Chapel did suffer badly during the Civil Wars, by order of the Long Parliament, in 1646, mainly because of the large number of statues, with which it was decorated. This chapel which was an empty shell only, never having been completed, would have been completely demolished, to make way for the new structure.

The plans were for a circular, domed building. The lantern of the dome was to be surmounted by a colossal statue of "Fame", with twenty large allegorical statues around the base of the drum. Wren also produced designs for the tomb itself; one to be made in bronze, another design for marble. In both designs the tomb was to be decorated with emblematical figures. Wren estimated the total cost of the tomb and mausoleum, to be over £ 43,000.

If it had been completed, the new mausoleum would have been a very impressive structure but it would, perhaps have been, to our eyes at least, an incongruous addition to the Gothic architecture of St. George's Chapel. Before the Bill in the Commons was passed, on July 15th, 1678, parliament was prorouged, and was not to meet again until October 21st. In the intervening period, the "Popish Plot" was discovered, and all thoughts of a tomb and mausoleum for Charles I, were forgotten. Parliament and the King struggled over the renewed persecution of Catholics, and the Bill of Exclusion, which was an attempt to prevent the Catholic Duke of York from succeeding Charles II. Charles assembled and dissolved

Parliament several times in the following years; the last Parliament of his reign meeting in March, 1681. For the last four years of his reign, Charles managed without Parliament. This perhaps shows, that Charles II was perhaps better able to deal with a rebellious Parliament, than his father, but because of this, the Bill was never passed, the monies were not available, and the monument to Charles I was never built. There are no records of James II, the second son of Charles I, ever considering the re-burial of his father, during his own, short, but troubled reign (1685-1688). It is doubtful if the following Stuart monarchs, Mary 11 and Queen Anne, ever con sidered any re-burial of their grandfather, who still lay, in an unmarked grave, in St. George's Chapel Windsor.

1649 to 1813

Whilst all the debates and discussions about re-burial were taking place, the small vault in St. George's Chapel remained undisturbed, but only for a short time.

During the short reign of James II, 1685-1688, the floor of the choir was re-paved. Presumably the existing floor had become worn through centuries of use. New paving stones of black and white marble were laid, which is the floor we see today. The work involved in laying this floor, must to some extent have disturbed the vault which lay immediately beneath the paving stones. The opportunity was not taken to mark the site of the vault.

In 1696 the vault was re-opened for another royal burial. This time a still-born daughter of the Princess George of Denmark. (The princess was later to become Queen Anne, after the death of William III). The birth must have occurred at Windsor, and this royal vault was probably considered to be the most convenient place of burial. Space in the vault was limited, and rather than placing the tiny coffin on the floor, it was laid on King Charles' coffn.

It is interesting that this particular vault be used, bearing in mind the discussions on the exact location of the vault, when the re-burial of Charles I was being considered. The exact site of the vault may well have been re-discovered with the re-paving of the choir, only a few years before.

By the reign of George III, 1760-1820, Windsor had become one of the royal families favourite palaces. George III decided to build a new burial vault in St. George's Chapel, for the use of his family. He chose a site for the new vault, beneath the floor of the large chapel, known then as "Wolsey's Chapel". This chapel was begun by Henry VII in 1494, but remained unfinished. Cardinal Wolsey resolved that this chapel should be his last resting place, but events overtook him, and this was not to be. Henry VIII also had plans to be buried in this chapel, but was in fact buried in a vault beneath the choir. The chapel remained unused, although as we have already mentioned, its future hung very much in the balance, when the site was considered for a mausoleum for Charles I.

At the start of the Nineteenth Century, the chapel was still an empty shell. It became known as the "Tomb House", and is known to us today as the Albert Memorial Chapel. The new vault was designed to accommodate forty-eight coffins, and was later to hold a number of important royal burials, including George III, George IV, and William IV Access to this vault is behind the High Altar, although when first constructed, an entrance was made through the floor of the choir, with a passage leading to the vault.

There is a large amount of space available beneath the floor of St. George's Chapel, with many burial vaults, made during the past centuries. Early in 1813, the Duchess of Brunswick (mother of the Princess of Wales) died, and preparations were made for her burial in a vault beneath the floor of the choir; a vault which must be adjacent to the old royal vault. This work, together with the construction of the entrance passage to the new royal vault, meant that there was a great deal of building and excavating activity in the choir area. During the course of this activity, the work men accidentally broke through a wall of the old vault. The builders may well have been aware that this vault was located somewhere in this area, but its exact Location and dimensions had probably been forgotten. Looking through the hole, three coffins were visible. The largest coffin was (rightly) assumed to belong to Henry VIII; a second coffin belonged to Queen Jane Seymour. From known accounts of the burial of Charles I, the third coffin, covered by a black velvet pall, was identified as his.

More Execution of Charles I

-

Introduction

Execution

Embalming

Cromwell

Charles I Coffin Opened (1813)

1813 to 1888

The Confession of Richard Brandon

Rainsborowe's Standard

Back to English Civil War Times No. 55 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com