The next morning Charles appeared calm, composed and prepared to face death. "Herbert," he said, "this is my second marriage day; I would be as trim today as may be, for before night I hope to be espoused to my blessed Jesus". Herbert helped Charles to dress, and combed his long hair.

The January weather was severe, it being so cold that the river Thames had frozen over. The King put on an extra shirt to keep the cold at bay. (The two shirts, reputedly worn by Charles on this day, still survive. One is in the possession of Her Majesty the Queen, and is kept at Windsor Castle; the second, of knitted blue silk, is in the Museum of London). Charles was concerned that the cold might make him shiver, and that any onlookers would see him shaking, and would think that he was afraid. "I fear not Death" said the King "Death is not terrible to me; I bless my God I am prepared".

Bishop Juxon arrived early, as Charles had requested, and he was allowed to be alone with the King for about an hour. Then Herbert was called into the room, and the Bishop said morning prayers. Shortly after this Colonel Hacker knocked at the door, entered, and told the King, "in trembling fashion", that the time had come to leave for Whitehall.

Bishop Juxon arrived early, as Charles had requested, and he was allowed to be alone with the King for about an hour. Then Herbert was called into the room, and the Bishop said morning prayers. Shortly after this Colonel Hacker knocked at the door, entered, and told the King, "in trembling fashion", that the time had come to leave for Whitehall.

At right, marble bust of Juxon, Bishop of London (1582-1663).

Charles put on his cloak, bearing the silver star of the Order of the Garter, in readiness for the journey from St. James's Palace to Whitehall. Colonel Tomlinson met the King at St. James's Palace, and walked, with his hat in his hand, on one side of Charles, with Bishop Juxon on the other, and Herbert following. This small group was immediately surrounded by two companies of Infantry which had been drawn up in readiness.

The procession marched off across the park, with drums beating loudly, and with colours flying. It was a dull, cold morning, and the ground was hard with frost. Charles reputedly asked the troops to set a quicker pace, he was himself a fast walker.

With the constant noise of the drums, conversation was difficult on the journey, but Charles exchanged some words with Colonel Tomlinson, expressing the hope that the Duke of Richmond would be allowed to take care of his burial.

The party ascended a wooden staircase, which led from the Park into the buildings of Whitehall. Walking along the gallery above the Tilt Yard, the King would have passed many family portraits, and many of the paintings from his great collection. Charles crossed over the main street by the upper floor of the Holbein Gate, from which he may well have been able to see the scaffold, and the waiting crowd.

Several of the newssheets state that the king arrived at Whitehall at about ten o'clock. At Whitehall, Charles received the Sacrament from Bishop Juxon. The Commissioners had met again, earlier this morning, and had issued another directive, that "..the scaffold upon which the Kinge is to be executed bee covered with blacke..", which was duly done.

The day wore on ... Charles had probably expected to be led to the scaffold early in the day, but he was cruelly kept waiting. This wait must have been extremely trying for Charles, but all those around him remarked how calm he was. Midday arrived, and a meal was prepared for the King. This offer of food was, however, refused, as Charles had resolved to touch no food or drink after receiving the Sacrament. Bishop Juxon, remonstrated with Charles, and persuaded him that he should eat something, as the weather was so sharp, that if he ate nothing, he might faint upon the scaffold. This argument convinced Charles, and he eventually ate about half of a small loaf of white bread, and drank a glass of claret. One account states that he initially asked for beer, as he had not expected there to be any wine left in the cellars of Whitehall.

EXECUTIONER

The Commissioners were at this time facing an unforeseen problem, as difficulty had been experienced in finding anyone to behead the King. Brandon, the official executioner, had been expected to perform the task, but when faced with the prospect, had refused in horror, stating that he would rather be I shot or otherwise killed, rather than do it".

There has been much debate, concerning the actual identity of the two executioners, and in particular, the man who wielded the axe. A written warrant would have been required, probably issued by either Hacker, Huncks or Phayre, but no documentary evidence has survived, and in its absence, the debate will no doubt, continue.

It would appear that the two headsmen were not finally selected until the day of the execution. Eventually, two men were found; both stipulated that they must be given a "disguise", so that their identity should not be known. The fact that Charles was not called to the scaffold until between one and two o'clock, can be attributed to the delay in finding the men, and in procuring their disguises.

It is often stated that the delay was caused by a last-minute sitting of Parliament, to pass an Act, prohibiting the proclamation of the Prince of Wales, as King. This may well not have been the case, for the previous Saturday, the House had passed an Act, which prohibited anyone being proclaimed King. On the actual day of the execution, many members of the House, may have deemed it prudent to be absent from the city of Westminster.

It is often stated that the delay was caused by a last-minute sitting of Parliament, to pass an Act, prohibiting the proclamation of the Prince of Wales, as King. This may well not have been the case, for the previous Saturday, the House had passed an Act, which prohibited anyone being proclaimed King. On the actual day of the execution, many members of the House, may have deemed it prudent to be absent from the city of Westminster.

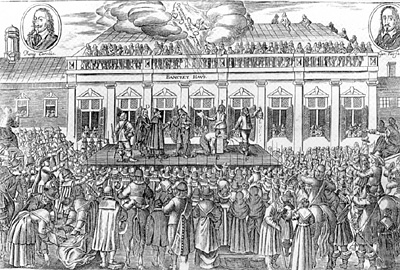

When, at last, the King appeared on the scaffold, the sun had broken through the clouds, and was shining brightly. The brightness must have seemed all the more intense to Charles, who had just come from the relative gloom of the Banqueting House. Several windows had been blocked during the wars, and what was once a light and airy room, had become a dark and empty shell.

The area outside the Banqueting House, was packed full of people. The space between the scaffold and the "rails", fixed to the bollards, was filled with soldiers. Outside the rails, troops of horses filled the street. Every possible precaution had been taken to prevent any rescue attempt, and also to ensure that any speech, or appeal made by the King, would be unheard by the public, who, beyond the ranks of soldiers and horse, would be able to see little, and hear less. Many people crowded the roof-tops of the adjacent buildings, and approached as close as they were allowed.

THE BLOCK

In the centre of the scaffold, opposite the middle window of the Banqueting House, stood the block ... a billet of wood about eighteen inches long six inches in height, flat a the bottom and rounded a the top. Near the block lay the axe.

In the centre of the scaffold, opposite the middle window of the Banqueting House, stood the block ... a billet of wood about eighteen inches long six inches in height, flat a the bottom and rounded a the top. Near the block lay the axe.

Contemporary Dutch engraving of the execution. The King is visible passing his George, (the insignia of the Order of the Garter), to Bishop Juxon. See enlargement elsewhere.

Four iron staples had been driven into the wooden floor of the scaffold which was littered with rope. The rope and the staples were there to be used to forcibly drag the King down to the block, if he offered resistance; this also accounted for the unusual lowness of the block.

A cheap deal coffin, which cost "but six shillings", lay to one side.

The small platform was quite crowded with people. Colonel Tomlinson and Bishop Juxon had come on to the scaffold with the King. (Herbert remained in the Palace of Whitehall, at the King's request). Colonel Hacker was there to see the sentence of the court carried out, along with several soldiers on guard, and two or three shorthand writers with notebooks and ink horns, to record the King's last words.

The two headsmen awaited the King, both wearing their disguises. One (who was later to hold up the King's severed head,) wore a large hat, "cocked up" the second (who struck the fatal blow), had on a "grey grisled periwig which hung down very low", and a "grey beard'. Both wore "visards", masks, covering the whole face, and they were dressed in close woollen "fro&", like those worn at the time by butchers or sailors.

The author of "The Perfect Weekly Account", wrote of Charles that, "No man could have come with more confidence and appearance of resolution", upon the scaffold, than did the King; "..viewing the block, with the axe lying upon it, and iron staples in the scaffold to bind him down upon the block in case he had refused to submit himself freely, without being any way daunted, Yea, when the deputies of that Grim Serjeant Death, appeared with a terrifying disguise, the King with a pleasant countenance said he freely forgave them".

Charles had been denied the right to speak fully at his trial, after the sentence had been passed. He was allowed to speak at some length on the scaffold. John Dillingham wrote in his "Moderate Intelligencer ... .... at his first coming he lookt upon the people who were numerous, as also the soldiers. Little appeared in the faces of any, either of joy or sorrow, those who had most cause to mourn, as greatest losers, being absent".

Charles's last words were, therefore, spoken to the fifteen or so people, present with him on the scaffold. During the course of his speech, he became concerned that the axe might be damaged; with all the obstacles on the floor of the scaffold that "one standing so neer the axe that his cloke touch'd it, which he seeing said, 'Do not hurt the axe, though it may me"'.

His speech ended, the King prepared for death. He spoke to the two headsmen. There is no account of the exact words, but he explained to them he would pray briefly, and then make a sign for the blow to be struck. He asked how he should arrange his long hair, so as not to impede the axe. With the help of Bishop Juxon, he put on a cap, and pushed his hair underneath it.

'THERE IS BUT ONE STAGE MORE'

"There is but one stage more" said Juxon, "which though turbulent and troublesome, yet it is a very short one; you may consider it will carry you a very great way; it will carry you from Earth to Heaven, and there you shall find to your great joy, the prize you hasten to; a Crown of Glory". Charles replied, "I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown here 0 disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world".

Charles then gave away the last of his few remaining possessions: He gave his "George" to Bishop Juxon, with the words "Remember..". It is thought that the Bishop had been instructed by Charles to give this to the Prince of Wales. His cane, he gave to the Bishop himself. His silver watch, and his gold watch, was left to the Duke of Richmond, (the gold watch being meant for the Duchess). His striking clock, he bequeathed to Herbert.

Charles then removed his doublet, and temporarily replaced his cloak against the cold. He looked again at the block, asking if it was set fast, and regretting that it was no higher. The executioner, probably being unwilling to explain the reason for its being so low, replied, "It can be no higher, Sir".

Charles stood for a moment, praying in silence. He then slipped off his cloak, and lay down with his neck on the block. The headman bent down to ensure that Charles' hair was not in the way; thinking that he was about to strike, Charles said, "Stay for the sign". "I will, an'it please Your Majesty", was the reply.

After a few seconds, the King stretched out his hands, the "bright ax" flashed, and at one blow, Charles' head was severed from his body.

After a few seconds, the King stretched out his hands, the "bright ax" flashed, and at one blow, Charles' head was severed from his body.

Few people would have actually seen the axe sever the King's head; when Charles lay down on the block, he would have probably been visible only to those who surrounded him on the scaffold, and to those perched on the surrounding buildings. It is also possible that the rails of the scaffold were draped with black cloth, which would have restricted visibility still further.

The second headsman held up Charles' severed head to the crowd. As the head was held high, the crowd gave, in the words of one eyewitness, "..such a groan as I have never heard before, and I desire I may never hear again".

It was customary practice at public executions, for the severed head to be held up to the crowd with the cry of "Behold, the head of a traitor". Many writers have asserted that this cry was given, but one specific account by an eyewitness, states that the executioner "said nothing", and none of the other many publications of the time contradict this. That this cry was not given, can be considered evidence that either headsman was not accustomed to his task, or, more probably, that he was afraid to call out, for fear that his voice be recognised.

The time when the fatal blow was struck, according to Sir William Sanderson, was within one minute of two o'clock.

THE KING IS DEAD

Before we look at the preparations made for Charles' burial, it may be useful at this point, to digress slightly, to see how we would expect to see a Seventeenth Century monarch buried, and to ascertain if, and/or how the burial of Charles I differs.

Upon the death of a monarch, the funeral arrangements would usually be made by contractors from the College of Arms. After the funeral of Queen Mary in 1694, the role of the College gradually fades from view, as the royal burials became private, rather than public events.

The first duty of the contractors, was the preparation of the body for burial, and then the arrangements for the funeral.

Since the Thirteenth Century, the bodies of monarchs were embalmed. The practise was markedly different from what most people today imagine embalming to be, as performed by the Ancient Egyptians, or by modern embalmers. The motivation was sanitation, not preservation. There was no attempt here to preserve the body because of any religious convictions, it was simply a question of trying to stop, albeit temporarily, the decomposition of the body.

Embalming seems to have been limited to royal burials, and in particular to deceased monarchs. There may well be specific reasons why this was so: When any ruling monarch died, it would have been considered essential that he be seen to be dead. News would travel slowly, and the more people who were able to see the body, and verify that the sovereign was dead, the faster the news would travel, and, most importantly, the news would be believed. This would help to ensure a smooth transition of power to the new monarch, for any doubt that the old king was dead, might disrupt the important early days of the new reign. It may also have been considered necessary that the body be seen, in order that it could be established, as far as possible, that death was as a result of natural causes, and not by any more sinister means.

These motives may not have been considered so essential by the Seventeenth Century, but by this time, embalming had become an established practice for the bodies of monarchs, and occasionally close members of the royal family. As a body will decay very rapidly, any attempt to limit the decay, even for a short while, would be practical if not essential. The body would probably be on view for one or two days after death, possibly slightly longer than this if death had occurred during the cooler months of the year. After this short period it would begin to discolour and smell. Even when placed in a coffin, an unburied body could still be decidedly unpleasant, especially as there could be a long delay between the date of death and the funeral: For example; Queen Mary II died in December 1694, but was not actually buried in her vault in Westminster Abbey, until March 1695. This long delay was probably not unusual. During this period, the elaborate plans and preparations for the funeral were put into effect, which would no doubt include the making of special suits of mourning for the officials, and the installation of stands and extra seating in the Abbey, the accommodate the large number of funeral guests.

These motives may not have been considered so essential by the Seventeenth Century, but by this time, embalming had become an established practice for the bodies of monarchs, and occasionally close members of the royal family. As a body will decay very rapidly, any attempt to limit the decay, even for a short while, would be practical if not essential. The body would probably be on view for one or two days after death, possibly slightly longer than this if death had occurred during the cooler months of the year. After this short period it would begin to discolour and smell. Even when placed in a coffin, an unburied body could still be decidedly unpleasant, especially as there could be a long delay between the date of death and the funeral: For example; Queen Mary II died in December 1694, but was not actually buried in her vault in Westminster Abbey, until March 1695. This long delay was probably not unusual. During this period, the elaborate plans and preparations for the funeral were put into effect, which would no doubt include the making of special suits of mourning for the officials, and the installation of stands and extra seating in the Abbey, the accommodate the large number of funeral guests.

This delay between the date of death and the funeral, also determined to so extent, the construction of the royal coffins, as we shall see later, but firstly the body had to be prepared.

More Execution of Charles I

-

Introduction

Execution

Embalming

Cromwell

Charles I Coffin Opened (1813)

1813 to 1888

The Confession of Richard Brandon

Rainsborowe's Standard

Back to English Civil War Times No. 55 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com