The following article first appeared in English Civil War Notes and Queries Nos 40-43 and is reprinted here, in full, to commemorate the anniversary of the execution. We have chosen to reuse this article instead of commissioning a new one as we consider this the best we have seen to date on the subject and wanted to give it the polish it deserves. He has recently written a book on the subject Published by Rubicon Press "Oh Horrible Murder".

INTRODUCTION

Many scholarly books have been written on the burial and

execution of King Charles I, and on the Civil Wars in general.

Many scholarly books have been written on the burial and

execution of King Charles I, and on the Civil Wars in general.

The reasons for, and the story of the Civil Wars will not be found here; nor will a detailed account of the burial of Charles I be given, or a full manuscript of his last speech on the scaffold. Such information is already well recorded elsewhere, and space does not permit its inclusion in this article.

The story here begins on January 27th, 1649, and continues into the Nineteenth Century: from the sentencing of Charles to death, to the exhumation and examination of his body in 1813. The story does not in fact end until 1888.

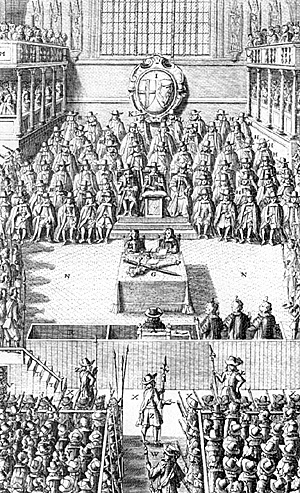

At right: print from "True copy of the Journal of the High Court of Justice for the Tryal of King Charles I." Often reproduced as a "contemporary," the style of dress indicates post 1649, but before 1684 (the only other date ascribed to the print).

The preparations for the king's execution is covered, the execution and the burial of his body. The 1813 account of the exhumation is often quoted in part, but is here reproduced in full. This account helps us to determine what happened to the King's body, following his execution, and before burial, and to ascertain how Charles' burial differs from what we would expect of a Royal burial of this period.

PREPARATIONS

It was well past one o'clock in the afternoon of Tuesday January 30th, when Charles anointed King of England, Ireland, Scotland and France, Defender of the Faith, stepped through a window of the Banqueting House in Whitehall, on to the scaffold .... The time had come.

Charles had risen early that morning, between five and six o'clock. He woke Thomas Herbert, who was sleeping on a pallet at his bedside. "I will get up," said Charles, "I have a great work to do this day."

Three days before this, on January 27th, Charles had received the sentence of the court:

"For all which treasons and crimes this Court doth adjudge that the said Charles Stuart as a tyrant, traytor, murtherer and publique enimy to the good people of this Nation, shall be put to death by the severing of his heade from his body."

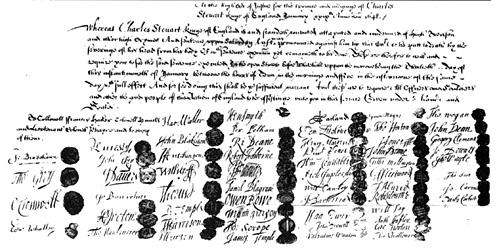

The Commissioners had agreed amongst themselves to sentence the King to death, on January 26th. The Warrant had already been drawn up, and by the end of that day had received some twenty- eight signatures. A few more signatures were added on the 27th, and eventually on Monday the 29th, the Warrant was taken to the Painted Chamber at Westminster. There, possibly after Oliver Cromwell and others had uttered a certain number of threats, most of the remaining Commissioners added their signatures. Ultimately, fifty-nine out of the sixty-seven Commissioners who had pronounced judgement on the King, signed and sealed the Warrant.

By the 29th, however, the Warrant was out of date. It was probably considered hazardous to attempt to draw up a second document, and have to obtain a further signature from each of the Commissioners, many of whom may well have already left London by this time. Alterations were therefore made to the date of the Warrant, and the names of Hacker and Phayre were substituted for the names of the two officers whose names had originally appeared. We can only assume that at the last moment, the original officers had refused to have any thing to do with the King's execution.

The actual Warrant still survives, and the alterations can clearly be seen. Strictly speaking, any such obvious alterations to a legal document, should be confirmed by all those sealing it, but this was not considered necessary, or was otherwise a deliberate oversight.

The Warrant, in its final form, was directed to three officers of the Army; Colonels Hacker, Huncks and Phayre, and it required that they, "See the said sentence executed in the open streete before Whitehall upon the morrowe, being the thirtieth day of this instate moneth of January, betweene the houres of Tem in the morninge and Five in the afternoone of the same day with full effect And for soe doing this shall be yor sufficient warrant..."

The Warrant also required..."All Officers and Souldiers and other the good people of this Nation of England to be assistinge you in this scrvix..."

The Commissioners also issued a further directive on the 29th

- "That the officers of the ordinance within the Towre of London, or any other officer of officer of the store within the Towre of London, or any other officers within the said towre in whose hands or custody the bright execucion ax for the executing malifactors is, doe forthwith deliver unto Edward Dendy Esqr, Serient at Armes attending this court, or his deputy or deputies, the said axe, and for theire or either of theire soe doeing, this shall be theire warrant."

Clearly any axe would not do, and there was one, special axe, kept at the Tower of London, for the express purpose of judicial decapitation. The Tower of London does not have any pre Civil War inventories which distinguish an execution axe. One of the first inventories listing a "heading axe", is dated 1675. The heading axe now on display at the Tower, has been identified as the axe of this inventory. Axes are particularly difficult to date, but this axe has been dated as 16th Century.

Clearly any axe would not do, and there was one, special axe, kept at the Tower of London, for the express purpose of judicial decapitation. The Tower of London does not have any pre Civil War inventories which distinguish an execution axe. One of the first inventories listing a "heading axe", is dated 1675. The heading axe now on display at the Tower, has been identified as the axe of this inventory. Axes are particularly difficult to date, but this axe has been dated as 16th Century.

The Earl of Holland and Lord Capell, were executed shortly after Charles, and, after enquiry, Lord Capell was assured by the executioner that it was the same axe as had been used to execute the King.

Tower Hill was the usual site for public executions. Many well known public figures had met their end there, where special stands were often erected to accommodate the vast crowds that turned out for such special events.

For the execution of the King, Tower Hill was no doubt considered, but the site chosen was at Whitehall, in the area outside the Banqueting House. This was a smaller, more enclosed space than Tower Hill. For this reason it could be guarded more easily Parliament did not want a last minute rescue attempt, therefore security was of the utmost priority.

Later, on the 29th, one of the many newssheets of the time, "The Moderate", reported that.. "Scaffolds are this day building and will be all night, in order to the King's execution". The same report stated that the Commissioners had "voted that the place of execution should be over against the Banqueting House of Whitehall".

The news spread fast.

- "The Kingdoms Weekly Intelligencer of the same date reported of the King that... "his children are now with him, howsoever it is believed on tomorrow he will suffer, and to that purpose, the way is now railed in from Whitehall to the Great Gate as you go to King's Street about the middle whereof it is said the scaffold will be erected".

The "Perfect Weekly Account" confirms this... "there are rails making at Whitehall (kite, and something else which it is thought will amount to a scaffold .... and it is probable that this is the place designed for execution".

A contemporary engraving by Hollar, helps to explain the meaning of these passages. It shows both Banqueting House, and the Whitehall Gate. The view is drawn from the north. A line of posts, or bollards as we would know them, runs from the north corner of the Banqueting House, turning at a right-angle to join the Whitehall Gate. It is reasonable to suppose that the "rails" erected, followed the line of these posts, and that within that area, against the facade of the Banqueting House, the scaffold was built.

A contemporary engraving by Hollar, helps to explain the meaning of these passages. It shows both Banqueting House, and the Whitehall Gate. The view is drawn from the north. A line of posts, or bollards as we would know them, runs from the north corner of the Banqueting House, turning at a right-angle to join the Whitehall Gate. It is reasonable to suppose that the "rails" erected, followed the line of these posts, and that within that area, against the facade of the Banqueting House, the scaffold was built.

Window to a Scaffolding

There has been much dispute, as to which window of the Banqueting House gave access to the scaffold. Many writers have been misled by errors in contemporary engravings, which show some of the windows blocked. It is commonly held that the window used was the second from the north Accounts state that the window was specially enlarged for this purpose. This window would have been at the north end of the scaffold, which ran from this window to the sixth window. We know that the scaffold was fairly large, for it was to accommodate at least fifteen people the next day.

Above the entrance to the Banqueting House today, is a bronze bust of King Charles I, and a plaque marking the place where Charles was executed. The inscription states that a window almost directly above the modern entrance, was used. This window no longer exists, it having been blocked up, and the wall plastered The faint outline of a window can, however, be seen beneath the plaster surface, which has some fine surface cracks, which follow the original window's outer edge When viewed from the pavement, this win dow is above and slightly to the left of the main door. This particular wall is set back some fifteen feet or so, from the main facade of the building. If we assume that the main por tion of the scaffold was built directly in front of the facade, and that this window was used, the scaffold's shape must have been "L" -shaped.

Looking at the main facade, and in particular at the stonework around the windows, there is no visible evi dence of any of the windows being enlarged; although of course it is possible that any repairs may have been expertly done, and with the passing of time, now be indistinguishable from the original stonework. It is diffi cult to see, however, how any of the windows could have been easily enlarged, without causing great damage to the stonework. It may be worth considering that the Banqueting House was at that time one of Westminster's newest and most prestigious buildings, built in the new Classical style by Inigo Jones. It would seem odd that such a building might be damaged in such a way, unless of course it was considered that it represented, with its extravagant style, all that was thought to be wrong with the Monarchy at this time.

One other possibility is perhaps a slightly different interpretation on the meaning of "enlarged". The large windows of the Banqueting House were not designed with openings at the level of the scaffold; "enlarged" may refer to the removal of part or whole of the wooden window frame, and the panes of glass, sufficient to make a doorway. Whilst this may not have been necessarily an easy task, it would have involved less actual damage, and replacement would have been relatively easy. There would have been a number of able carpenters already on site, involved in the work of building the scaffold.

Clearly, unless or until further documentary evidence is discovered, this particular debate will continue.

Hammond, the Master Carpenter at Whitehall was ordered to provide the scaffold. He employed one Robert Lockier to erect the scaffold. Lockier was paid at the rate of 2s. 6d. a day for his work. There would have been a fairly large number of workmen also employed, to fetch and carry, and to saw and nail together the large timbers used to make the scaffold.

At about five o'clock on the 29th, the King was carried back to St. James's Palace, to spend his last night. It is thought that this was done so that he should not be disturbed by the constant hammering of the workmen at Whitehall. The building of the scaffold would continue throughout the night.

As Charles had anticipated, many people called to see him, including his nephew, the Prince Elector, the Duke of Richmond, the Marquis of Hertford and the Earls Southampton and Lindsay, but Charles refused to receive them.

At St. James's Palace, Charles was allowed a final, brief meeting with two of his youngest children, who were being kept in London; Princess Elizabeth, aged thirteen, and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, aged eight. Charles impressed on them both that they should no longer look upon the Prince of Wales as their eldest brother, but as their Sovereign. It must have been a distressing meeting for all, but Charles spoke plainly to his children. He was anxious that they should know exactly what would happen to him the next day. "They will cut off my head", Charles said to Prince Henry, and he then told him that he must not allow Parliament to make him a king, "As long as your brothers Charles and James do live".

"I will be torn in pieces first", was the reply, which greatly pleased Charles.

Charles then gave his children the few remaining pieces of jewellery still in his possession, "save the George he wore". The George being the insignia of the order of the Garter, which Charles was to wear to the scaffold. Charles asked Princess Elizabeth to tell her mother, Queen Henrietta "that his love should be the same to the last..."

He then kissed the Prince and Princess, gave them his blessing and bad them farewell. Charles turned away from them as they left the room with Bishop Juxon. He walked quickly into his bedchamber, and lay down on the bed; his legs were trembling.

What was left of the evening was spent in prayer and quiet meditation with Bishop Juxon. Some hours after darkness fell, the Bishop left; Charles had requested that he return early the next morning. Charles sat up reading and praying until nearly midnight, and then retired to bed, sleeping peacefully for several hours. As usual his bedchamber was lit by a burning wax candle, placed in a silver basin.

More Execution of Charles I

-

Introduction

Execution

Embalming

Cromwell

Charles I Coffin Opened (1813)

1813 to 1888

The Confession of Richard Brandon

Rainsborowe's Standard

Back to English Civil War Times No. 55 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com