THE KHALIFA TAKES CONTROL

The fall of Khartoum, the death of Gordon, and the failure of the Gordon Relief Expedition soon caused the British public to lose interest in the Sudan . . . and the Gladstone government.

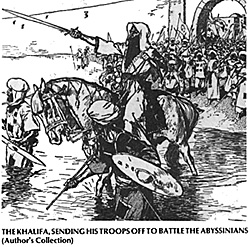

THE KHALIFA, SENDING HIS TROOPS OFF TO BATTLE THE ABYSSINIANS (Author's Collection)

THE KHALIFA, SENDING HIS TROOPS OFF TO BATTLE THE ABYSSINIANS (Author's Collection)

The change in government meant a change in policy and, at least initially, the new policy was one of revenge. By the time the state of the army in Egypt was evaluated, however, it was found that at least a year would be needed for regrouping, re-equipping and reinforcing Wolseley's troops for a major expedition into the Sudan. Rather than spend all that time (and money) on an expedition of questionable value, the decision was made to forget about the Sudan and withdraw to the Egyptian frontier (except for a strong garrison at Suakin on the Red Sea). The Sudan would be left to the Mahdists to run as they wished.

The sudden death of Muhammad Ahmad, likewise fouled-up the plans of the Mahdists. It was hoped to follow the Khartoum operation with a large-scale invasion of Egypt. The death of the Mahdi and the ascension to power of the Khalifa caused the postponement of the Egyptian invasion. The Khalifa had expected at least a minor power struggle between the Mahdi's supporters, the Ashraf, and his own factions. Surprisingly, all the powerful amirs, the members of the Mahdi's family and the Ashraf all swore allegiance to Abdallahi as the "khalifat al-Mahdi" (the Mahdi's successor).

Despite his ease of ascension to power, the Khalifa spent the better part of a year solidifying his position as the leader of the Sudanese people. Consequently, the Mahdist military machine was not very active during the period of the change of power. The Khalifa was rewarded with two victories in the summer of 1885, the capture of Kassala and Sennar, the last two Egyptian outposts in the interior of the Sudan. As these operations were begun under the Mahdi's reign, however, they cannot be totally attributed to the Khalifa. The first major military operation undertaken by the Kahlifa was the intermittent war with Abyssinia, which lasted from 1887 to 1889.

THE ABYSSINIAN WAR AND THE RELIEF OF EMIN PASHA

The reasons behind the Abyssinian war are very vague. It seems most likely that both the Khalifa and King John wanted to prove between themselves who was the best man. For two years the armies of these two African nations threw themselves at each other with no real advantage ever going to either side. The Abyssinians attacked first, capturing Gallabat, then burning the village and retiring.

The Khalifa sent the Emir Yunis al-Dikaim to retaliate. Instead, Yunis re-established peaceful relations with the Abyssinians. After a period of regular trade, Yunis and his troops descended upon the Abyssinians and sent nearly 1,000 of them to Omdurman as prisoners. The Khalifa sent a message to King John demanding the return of Sudanese prisoners and inviting him to denounce Christianity and join the Mahdist movement.

King John did not reply to Abdallahi's message, but the massing of an Abyssinian army on the Sudanese border pretty much served as a reply to the Khal ifa. Hamdan Abu Anja, the best Mahdist general was quickly summoned to Omdurman. In June of 1887, an army of 30,000 ansar followed Abu Anja to do battle with the Abyssinians. By the time the Mahdists reached Gallabat, their numbers had doubled. King John's troops were nowhere to be seen, so Abu Ania did not hesitate to invade Abyssinia.

The Abyssinians, under the command of King John's best general, Ras Adal, had withdrawn to the plain of Debra Sin, where they awaited the Mahdists. Heroic charge followed heroic charge as the Abyssianians threw themselves against the Mahdists. Again and again, Abu Anja's jihadiyya riflemen broke up the Abyssinian charges and threw them back in disorder. Finally, the ansar spear and swordsmen were released and the destruction of Ras Adal's army was complete. The Mahdists advanced to Gondar (30 miles away) and sacked and burned the town. They then returned to Gallabat with many prisoners and much booty.

Though the defeat of the Abyssinians at Debra Sin did not mark an end to the fighting on this front, hostilities did not resume for over a year. Meanwhile, in the south and northeast (around Suakin) other events of interest were happening. In the southern provinces of Equatoria, he Egyptian government was still in control, under the military governor, Emin Pasha. At Suakin, Uthman Diqna was preparing to besiege the British and Egyptian garrison.

The story of Emin Pasha and his subsequent "rescue" is, perhaps, one of the most fascinating side-lights to the whole era of the Sudan Wars. When the British public heard that Emin Pasha, hopelessly cut-off in Equatoria, was still holding on, an immediate call for a rescue mission was sounded. The memory of Gordon's death and the fall of Khartoum was still fresh in the minds of the English people and they let it be known that they would not allow another Western Christian (Emin was born Eduard Schnitzer in Germany) to be abandoned to his fate at the hands of the Mahdists. The government, not wishing to get involved in any sort of official relief attempt, "allowed" a private relief expedition to be organized. To lead the expedition, the greatest African explorer of the era was chosen, Henry M. Stanley (of "Dr. Livingstone, I presume" fame).

Expedition

Despite the shorter distance and easier approach to Equatoria through East Africa, Stanley lobbied hard for, and won approval of a route from West Africa, up the Congo and Aruwami Rivers and through hundreds of miles of unexplored territory. Loaded with trade goods, guns, ammunition, a Maxim gun and a collapsable metal boat, the expedition left Zanzibar on February 25, 1887. Fourteen months later, the tattered "Advance Guard" of Stanley's expedition met with Emin on the shores of Lake Albert. It was not until the end of December, 1888, that all of the relief expedition made it to Equatoria. Only 233 of the 807 who left Zanzibar remained.

When Stanley informed Emin that he had to leave, Emin was dumbfounded. Stanley's expedition seemed to be more in need of "rescuing" than the Egyptian garrison and its leaders. Finally, virtually at the point of a gun, Emin marched out of Equatoria with Stanley and his men. In September of 1889, they arrived back at Zanzibar. The relief expedition took 2 1/2 years and cost nearly 600 lives, and Emin didn't really want to be rescued!

At Suakin, Uthman Diqna closed in a tight siege after receiving reinforcements from Omdurman in September. The Egyptians, fearing the loss of the important Red Sea port, reinforced the garrison up to nearly 5,000 men. In mid-December, 1888, a surprise sortie caught the Mahdists napping in their trenches and the siege was broken. For the time being, Suakin was safe and Uthman Diqna's military advances were checked.

Meanwhile, on the Abyssinian front, things were once again heating up. During 1888, King John had sent spies under the cover of peace negotiators to Omdurman. The Khalifa, suspicious as always, rejected the emissaries and again urged the Abyssinians to join the Mahdist cause if they truly wanted peace.

King John, tired of the Khalifa's one-track mind, replied that he would personally lead an army to Gallabat and avenge the defeat of Ras Adal. Both sides began building up their armies for the resumption of hostilities in early 1889. The Khalifa again turned to Abu Anja as his commander, but, early in 1889, this ablest of Mahdist generals died while attempting to cure himself of indigestion with some local herbs.

Zaki Tamal replaced Abu Anja and quickly set about entrenching his army at Gallabat. He had a deep ditch and two concentric thornbush zeribas constructed around his position. The second zeriba was designed as a final defense and did not enclose the village. Satisfied with his defense, Zaki Tamal sat back and awaited the arrival of King John and the Abyssinian army.

At dawn on the 9th of March, 1889, the Abyssinians advanced and began throwing themselves with reckless abandon against the Mahdist positions. After five hours, the ditch had been crossed and the first zeriba breached. The Abyssinians poured into the village and began burning and killing everything in sight. Zaki Tamal and the remains of his army withdrew to the inner zeriba and prepared to die for Allah and the Khalifa.

Just as things looked darkest for the Mahdists, a stray bullet struck and killed King John. As the news of the death of their King spread through their ranks, the Abyssinians lost heart and withdrew from the field carrying what loot and prisoners they could. The astonished Mahdists watched, in amazement, as the army that was about to overwhelm them, disappeared into the hills. Once they heard what had happened, a pursuit was ordered.

Three days later, the King's bodyguard was defeated at the river Atbara. The King's head was sent in triumph to Omdurman. The Abyssinian war was over. Little was gained by either side. Both sides paid heavily in lives, and both sides lost able generals. The death of Abu Anja was perhaps the more serious as the Mahdists never again had a military leader of his qualifications. Possibly the most significant event to emerge from the Abyssinian campaign was the final battle of Gallabat. It was the last time that large armies clashed with predominantly melee weapons-the last time where masses of men looked each other in the eyes as they hacked and stabbed with swords and spears. Classic warfare was now truly dead!

More Sudan Part II

- The Khalifa Takes Control, 1885

The Invasion of Egypt, 1889

The Dongala Expedition, 1896

Advance to Omdurman, 1897

Battle of Omdurman, 1898

More Sudan

-

The Sudan Part I: Introduction: The Mahdi

The Sudan: First British Involvement 1884-85

The Sudan: Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Map

The Sudan: Illustration: Troop Types of Hicks' Expedition (slow: 139K)

Sudan War Bibliography

Lynn Bodin: Bio of Theme Editor for Sudan

Whalers on the Nile: Sudan Transport Boats

Wargame Figures for the Sudan

Colonial Era Wargame Rules Overview

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com