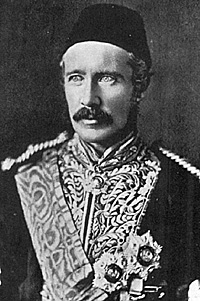

Just the mention of names such as Gordon (at right: photo from author's collection),

Kitchener, the Mahdi and the Khalifa brings to mind such

epic battles as the Siege of Khartoum, Tamai, El Teb, Abu

Klea, Atbara and Omdurman.

Just the mention of names such as Gordon (at right: photo from author's collection),

Kitchener, the Mahdi and the Khalifa brings to mind such

epic battles as the Siege of Khartoum, Tamai, El Teb, Abu

Klea, Atbara and Omdurman.

Ah, the British Empire at its peak! The Camel Corps marching across the burning desert, the rattle of the Gatling guns, the smell of black powder and the bugle calls to "Form Square!" all make us think of the Sudan. The Sudan campaigns were far more, however, than just the Siege of Khartoum, the not-quite-in-the-nick-of-time Gordon Relief Expedition, and the reconquest culminating in the Battle of Omdurman.

For nearly two decades, the British Empire was involved, either directly or indirectly, in the military affairs of the Sudan.

The history of the Sudan can be divided into roughly four distinct eras during the time period 1881-98;

- 1) the rise of the Mahdi and the defeat of the

Egyptian Army, roughly 1881-83,

2) the era of the first British involvement, 1884-85,

3) the rebuilding of the Egyptian Army, 1886-95, and

4) the reconquest of the Sudan, 1896-98.

This article, the first of two, will provide an overview of the first two eras.

THE RISE OF THE MAHDI, 1881-83

The Sudan was ripe for revolution in 1881. Memories of the brutal Egyptian conquest still lingered in the minds of the people. The Khedive Ismail's suppression of the slave trade had stirred up many ill-feelings towards the government in Cairo. Excessive taxes had drained the region of much of its economy. Favoritism shown by the government towards certain tribal and religious groups had reached unreasonable limits. The fuel for a revolt was spread across the Sudan and awaited only the proper match to set it ablaze.

At right, Muhammad Ahmad, photo from author's collection.

At right, Muhammad Ahmad, photo from author's collection.

That match came in the form of a 37-year-old son of a boat-builder from Dongala, Muhammad Ahmad. The young Muhammad, unlike his three brothers who followed their father's trade, chose to study religion. By the year 1868, the then 24-year-old Muhammad had been made a shaykh of the Sammaniya order of Islam and was travelling throughout the region on religious missions. For more than 10 years Muhammad preached among his people and witnessed their oppression at the hands of the "Turks" (as he referred to the Egyptians).

Finally, in 1881 after a very prophetic encounter with Abdallahi b. Muhammad (later to become the Khalifa Abdallahi, the Mahdi's successor) Muhammad Ahmad realized that he may very well be the Mahdi, the "Expected One", of Islamic teachings.

The Governor General of the Sudan, Rauf Pasha, had not been ignoring the rise of the Mahdi. When Muhammad Ahmad called a hiria (the flight for the Faith from among the infidels to the Mahdi) in the summer of 1881, Rauf Pasha acted. Rauf sent his assistant, Muhammad Bey, to invite the Mahdi to come to Khartoum (where Rauf intended to arrest Muhammad Ahmad) on 7 August 1881. The Mahdi, needless to say, rejected the summons. The Governor General wasted no time in responding. He sent Aby Su'ud with two companies of regulars to Abba on 12 August to take the Mahdi by force.

Though he had only 313 men (the same number which the Prophet had in his first battle), Muhammad Ahmad was confident of victory over the infidels. Abu Su'ud's plan of attack was sound, but it was executed poorly by over-zealous officers who were anxious to receive the promised promotion forthe first man to bring in the Mahdi.

During a night march in which the Egyptian forces were split, the Mahdists ambushed and routed the Egyptian regulars. Abu and the survivors streamed back to Khartoum while the Mahdi's troops buried their 12 casualties. The victory was seen as a miracle by the Sudanese. Thousands now flocked to the Mahdi where previously only handfuls had come.

More Defeats

More Egyptian expeditions followed, and they too were defeated. In October of 1881 Rashid Bey and 1200 men were wiped out at Khur Maraj. In May of 1882 al Shallali and another Egyptian column were annihilated at Jebel Jarrada. The Mahdi was now ready to assert his control over the entire province of Kordofan. He led his army, now swollen to over 50,000, to besiege the provincial capital of El-Obeid.

El-Obeid proved to be a tough nut to crack. Defended by 6,000 well-armed Egyptian regulars behind 20-foot thick walls, EI-Obeid could hold out for months. On 1 September 1882, the Mahdi offered surrender to the governor of Kordofan, Muhammad Said. Said hung the Mahdi's emissaries. A week later the Mahdi's army attempted to storm the city. They were thrown back by the disciplined fire of the Egyptian regulars' Remington rifles. Muhammad Ahmad's losses were in the thousands. A quick reassessment of his tactics was made and he decided to allow his troops to use some of the rifles captured from the Egyptians--up to this time the Mahdi had restricted his troops to using "traditional" weapons such as swords and spears. The siege tightened and EI-Obeid fell on 17 January, 1883, only days after the garrison at Bara had also surrendered. Muhammad Said and all the high-ranking officers were executed and all surviving troops were pressed into the service of the Mahdiyya. EI-Obeid and Kordofan were sacked and Darfur province (further to the west) was hopelessly cut-off.

The Government was now in a tough spot. A decisive victory over the Mahdi was needed quickly or the entire situation in the Sudan would decay beyond the point of no return.

Hicks

In late January the new Governor General of the Sudan, Abd el Kader, appointed Colonel William Hicks (late of the Indian Army) to the post of Chief of Staff. Hicks, at times hindered by Egyptian meddling, went about the task of organizing the troops available to him in the Sudan.

Colonial William Hicks. Photo from author's collection.

Colonial William Hicks. Photo from author's collection.

On 29 April, Hick's forces defeated a sizeable Mahdist force at Jebel Ain. The Egyptians suffered only seven casualties while the Mahdists lost over 500, including 12 high-ranking amirs. Hicks, elated, began planning the reconquest of Kordofan.

The Egyptian Army in the Sudan had always consisted of the rejects and cast-offs from the Army in Cairo. Service in the Sudan usually meant punishment for some crime or military mistake. Hicks, wishing to improve the quality of his troops, requested some of the newly reorganized and retrained Egyptian Army, which was now being formed under the watchful eyes of the British authorities. Cairo rejected Hicks' request and, instead, sent him 3,000 questionable troops which included 1,800 of Arabi-Pasha's former mutineers and several hundred men rejected as "unfit for service" by the new Egyptian Army.

Hicks, after several threats to resign, finally decided to do the best he could with what he had. On 9 September, 1883, 8000 troops with 14 guns, 6 Nordenfeldt machine guns, 5500 camels, 500 horses and 2000 camp followers marched out of Khartoum with the re-capture of El Obeid as their objective.

For two months the Hicks Pasha expedition fought heat, thirst and Mahdists on their way to EI-Obeid. The Mahdi spent the time training his army (now estimated at 60,000) for one decisive battle at a location of his choosing. On 5 November 1883, in the thorn forests of Shaykan, Hicks and his 8,000 men were overwhelmed and annihilated by Muhammad Ahmad's army. All of the Sudan south of Khartoum was now the Mahdi's for the taking.

As if the Hicks disaster was not enough, the Egyptian army was doomed to yet another major defeat before things got better. After the fall of EI-Obeid, a very influential and powerful Sudanese leader joined forces with the Mahdi. Uthman Digna (spelled Osman Digna by westerners) declared his allegience, and that of his Hadenclowa followers, to the Mahdiyya (the Mahdist state). The Hadenclowa tribe of the Beja were the famous "Fuzzy-Wuzzies" of Kipling's poem. The eastern Sudan, that is the area between the Nile and the Red Sea, now became hostile to Egypt.

The major caravan route between Suakin (on the Red Sea) and Berber (on the Nile) was no longer safe. The Egyptian garrisons of Tokar and Sinkat were besieged by Uthman's Hadenclowa tribesmen at about the same time as the destruction of Hicks' expedition. Small Egyptian relief columns were wiped out on 26 October, 5 November and 2 December 1883.

By this time, the authorities in Cairo recognized the severity of the situation around Suakin. The British, however, refused to allow the newly reorganized Egyptian Army to be used in this "side show" campaign. Instead, a special force of gendarmes and black volunteers was organized under Valentine Baker Pasha and sent to Suakin. This relief column was of about the same quality as Hicks Pasha's force. The gendarmes, who had joined the police force to avoid military service, resented being sent out of Egypt on a purely military expedition. The black troops were to be commanded by al-Zubayr Pasha, but when Britain protested the appointment of an ex- slavetrader to a military post, Zubayr was removed. The value of the black troops without Zubayr was quite limited.

On 4 February, 1884, Baker and 3,656 troops marched out of Trinkitat towards Tokar. They were met by Uthman's natives and routed. Over 2,000 Egyptians were killed and Baker and the remnants of his force returned to Suakin. The situation at Sinkat was now desperate. The commander, Muhammad Tawfiq, realized his situation and decided to attempt a fighting withdrawal on 8 February. The guns were spiked and the garrison marched out, accompanied by their women and children, in a large square. Within a mile of Sinkat they were met and defeated by Uthman's forces. Fifteen days later, Tokar surrendered.

More Sudan

-

The Sudan: Introduction: The Mahdi

The Sudan: First British Involvement 1884-85

The Sudan: Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Map

The Sudan: Illustration: Troop Types of Hicks' Expedition (slow: 139K)

Sudan War Bibliography

Lynn Bodin: Bio of Theme Editor for Sudan

Whalers on the Nile: Sudan Transport Boats

Wargame Figures for the Sudan

Colonial Era Wargame Rules Overview

Sudan Part II: The Khalifa Takes Control, 1885

Sudan Part II: The Invasion of Egypt, 1889

Sudan Part II: The Dongala Expedition, 1896

Sudan Part II: Advance to Omdurman, 1897

Sudan Part II: Battle of Omdurman, 1898

Mahdist Armies: Introduction

Mahdist Armies: Early Battles and Uniforms 1883-1885

Mahdist Armies: Later Battles and Uniforms 1889-1898

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com