In January, 1424, Zizka was again dealing with his major enemy -- the Royalists. He moved north to oppose the troops of Lord John Mestecky and Lord Puta of Castolovice. A battle was fought near Skalice on 6 January, with the Royalists again being defeated and losing many prisoners. Two months passed before there was a major engagement. With the end of the Hussite truce in March, Zizka attacked John Krusina's castle of Hostinne in retaliation for aiding the Catholic lords of the north in January. The attack, though spirited, failed.

Frustrated, Zizka decided to settle another score -- against a Royalist. He attacked the castle of John Cernin at Mlazovice to avenge Cernin's killing of Lupak in 1423 at Tynec. The castle was demolished, and Cernin was executed.

During the period of the Prague/Orebite turmoil the city of Tabor, under Bohuslav of Svamberg,s military leadership remained neutral. In April and May, 1424, the Pilseners once more began operations against Zizka, while the Taborites did not oppose them. Without allies, Zizka reacted by planning to hit the Pilseners in their home region one hundred and fifty miles distant. A difficult operation to accomplish with an army coming from the Orebite region with its severely limited resources, the ever-clever Zizka managed to assemble an army of 500 cavalry, 7,000 infantry, and 300 wagons. The march began.

By May he was operating in Pilsener country between Klatovy and Pilsen. A force of 300 sympathetic troops from Klatovy and some soldiers from Susice joined the Orebite army. Moving north, Ziska carefully avoided major Pilsener forces near Kralovice, while rallying additional support from Zatec and Louny. However, when in late May Prague decided to join the Pilseners, Zizka's future appeared bleak. He marched east to the Elbe valley at Roudnice, then moved south in an attempt to reach Caslav. At the small town of Kostelec northeast of Prague the combined Pilsener/Praguer army hit Zizka on 31 May. He barely had enough time to assemble his wagon fortress on a slight rise before the troops of Hasek of Waldstein were upon him. Zizka was besieged for three days before he was able to send word to allies of his plight.

Hynek Bocek from Podebrady castle slipped near Zizka's position with some river ferries and evacuated the troops in the middle of the night of 4 June. At dawn the besiegers were astonished to discover that Zizka the magician had made good another escape.

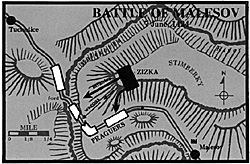

Out of the trap, Zizka again set his troops marching toward Caslav, with the Praguer army in fast pursuit. On 7 June, Zizka decided to make a stand at Malesov. He placed his forces on a hill overlooking the road running through the river valley. He ordered his supply wagons loaded with rocks and positioned at the edge of the slope, then waited for the Praguers to advance along the road. After half of the enemy force had passed his position, Zizka ordered the rock-laden wagons released down the slope.

Out of the trap, Zizka again set his troops marching toward Caslav, with the Praguer army in fast pursuit. On 7 June, Zizka decided to make a stand at Malesov. He placed his forces on a hill overlooking the road running through the river valley. He ordered his supply wagons loaded with rocks and positioned at the edge of the slope, then waited for the Praguers to advance along the road. After half of the enemy force had passed his position, Zizka ordered the rock-laden wagons released down the slope.

Their column torn asunder, the Praguers milled about in total confusion. After blasting the muddled Praguers with a sharp artillery salvo, the Orebite infantry hurtled down on the remnants. A disproportionate slaughter ensued; the Praguers lost 1,400 killed, Zizka lost 200. As a result of this victory Zizka was able to proceed unmolested. He marched triumphantly on Kutna Hora, which promptly surrendered without a fight. That act set the trend for the towns of Kourim, Cesky Brod, and Nymburk to follow when the Orebite army approached. After the battle of Malesov Praguer military power collapsed, and Jan Zizka had re-asserted himself as the premier military commander in Bohemia.

In mid-June, 1424, Zizka was active in northeast Bohemia, conquering Turnov. By July his troops had fought their way to Ostromec castle south of Prague. The successful occupation of the castle blocked the lines of communication to the capital. Throughout the month of August, the Orebite troopers were inactive as Zizka reorganized and refitted them for a new campaign. By September he was ready to march on Prague and encamped at Liben within sight of the Vitkov. Intermediaries stepped in to try to prevent a pitched battle and siege. Finally one of the negotiators, John Rokycana, mediated an agreement resulting in Zizka's military brotherhood and federation being recognized by the leaders of Prague.

The success of this agreement was soon evidenced by the fact that Zizka led a combined Hussite army on a campaign into Moravia beginning on 3 October. Prior to crossing the border they laid siege to Lord Cenek of Ronov's Pribyslav castle. Tragedy struck as Zizka (nearly 64) fell ill with the plague and died on 11 October. His grieving army renamed themselves the "Orphans" and overran the castle in one massive charge. Zizka's body was carried back to Caslav where he was buried as a great Bohemian national hero.

The decade following Zizka's death saw the leadership of the military brotherhood passing to Prokop the Bald of the Taborite community. With the Orphans army he embarked on campaigns into Austria, Hungary, and Germany, and sent an expedition under John Capek to Poland to defeat the Prussian Order. The Hussite soldiers became as respected and feared in Europe as the Swiss mercenary pikemen. The wagon forts would eventually be copied and integrated into some foreign armies that fought the Turks in the latter half of the 15th Century.

Prince Korybut had been eclipsed by Prokop as the actual leader of Bohemia. Although regent, Korybut fled for Poland after his plot to return the Hussites back into the Church in return for the Bohemian crown was exposed. This marked an end to foreign influence into Hussite internal affairs.

Two more anti-Hussite crusades were attempted; both failed disasterously and the Church finally entered into serious negotiations with the Hussites in 1433 at Basel. While these lengthy negotiations were in progress, Prokop led an 18,000-man army against the 25,000 troops of the Catholic league under Divis Borek at Lipany. On 30 May, 1434, Borek attacked with his infantry and was repulsed. The Royalists deliberately retreated to give the appearance of having been defeated. When the Hussites swarmed out of their wagon fortresses to pursue, Royalist cavalry that had been lurking concealed in nearby woods rushed forward to disperse the Hussite infantry and overrun the wagon forts. Some 13,000 Hussites were slain, another thousand incinerated after surrendering, and Prokop was fatally wounded. After fifteen years of fighting, the Hussite field armies were destroyed.

Elated at the news of this Hussite calamity, Church negotiators at Basel believed that the Bohemian menace had finally been eliminated. It had not. The Hussite revolution was a popular, well-established nationalistic movement which one defeat in battle could not erase. It took the Roman Church some time to accept this fact, but eventually they compromised with the Bohemian heretics, signing an agreement at Basel in July, 1436, ratified a year later. The era of the Hussite wars was over, but Zizka's legacy -- the concept of a Czech nation -- would endure to the present time. Although theologians may formulate the concepts of religious reform, Ziaka demonstrated that new religions, like nations, must at times be forged in iron and blood.

Postscript

Admittedly, the Hussite wars (1419-1434) are not one of the most familiar periods of human history. The number of English-language texts devoted to the wars could easily be counted on one hand. This publication is one of the first attempts to bring the story of this period to the English-speaking public. There is simply nothing available on the subject in any but the most comprehensive municipal libraries; the information utilized in this writing was painstakingly extracted in university libraries from academic texts written in the convoluted prose so dear to professors and doctoral candidates.

General reference works, such as encyclopedias, contain rather brief entries describing this period of turmoil as a religious conflict fought in Bohemia during the 15th Century. Unfortunately, such cursory accounts do justice to this critical era of Czech history about as accurately as saying that World War Two was nothing more than a conflict of short duration fought in Europe and Asia during the 20th Century. The Hussite wars were the culmination of one of the most significant phases in the long evolutionary struggle of Christianity and of the Roman Church in particular.

The 15th Century religious reformation centered in Bohemia was the true birthplace of Protestantism a hundred years before the emergence of Luther or Calvin; and the resultant nationalistic resistance of the Czech people occurred long before Jeanne d'Arc called upon Frenchmen to rise up in defense of their fatherland.

Even the combat of the Hussite wars left an indelible mark on the nature of man's wars. The fundamental changes in tactics, strategy, and military organization wrought in that era have had a profound impact on succeeding conflicts around the globe. Jan Zizka, author. of that military revolution, was an innovator and battlefield leader to rival the likes of Napoleon or Rommel. The influence of German scholars on English-speaking writings has had a pemicious effect on Zizka's niche in history.

Reflecting their anti-Hussite hias, German scholars have portrayed Zizka as a latter-day Attila the Hun in bestiality, ignoring his contributions to the military art and Czech nationalism. Obscured for centuries by a German anti-Czech conspiracy, it is time Jan Zizka assumed his rightful place in the pantheon of great military leaders.

We sadly live in a time of "relevancy;" aside from a handful of academicians, the chroniclers of our history are singlemindedly engrossed in the microscopic dissection of our contemporary existence. Pre-19th Century history has been all but condemned as passe and really not worth the time of the modern historian. The Hussite wars might reasonably be called old, but that does not mean they have to occupy a dry, nondescript place in history. The saga of the wars can be interesting, informative, and "relevant." At a time when historians seem interested only in popular history, the author has endeavored to make a small fragment of history popular.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frankenberger, O. Nase velika armada (Our Great Army). Prague, 1921.

Heymann, Frederick G. John Ziaka and the Hussite Revolution. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1955.

George of Bohemia. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1965.

Hoch, K. Husite a ualka (The Hussites and War). "Ceska Mysl," 1907.

Kaminsky, Howard. A History of the Hussite Revolution. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1967.

Kuffner, H. Nusitske-vojny u obrazech (Hussite Campaigns in Pictures). Vinahrady, 1908.

Lutzow, Franz H. Lectures on the Historians of Bohemia (Being the Ilchester Lectures for the Year 1904). London: Henry Frowde, 1905.

Lutzow, Franz H. Bohemia. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1909.

Lutzow, Franz H. The Hussite Wars. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1914.

Macek, Josef. The Hussite Movement in Bohemia. Prague: Orbis, 1958.

Mladonovice, Petr. John Huss at the Council of Constance. (Matthew Spinka, translator). New York: Columbia University Press, 1965.

Neumann, A. K ualecnictui za doby husitske (Warfare in Hussite nmes). "IBaika, XXXVII," 1920.

Odlazilik, Otakar. The Hussite King. New Brunswick, New, Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1965.

Schaff, David S. John Huss. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1915.

Seton-Watson, Robert W. A History of the Czechs and Slovaks. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1965.

Tierney, Brian. Foundations of the Conciliar Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1955.

Toman, H. Husitske ualecnictvi za doby Ziekovy a Prokopovy (Hussite Warfare in the Times of Zizka and Prokop). Prague, 1898.

Urbanek, R. Lipany a konec polaich vejsk (Lipany and the End of the Field Armies). Prague, 1934.

Vickers, Robert H. History of Bohemia. Chicago: Charles H. Sergel Company, 1894.

Wagner, E. Jak ualcili Husite (How the Hussites Waged War). Prague, 1946.

More Hussite Wars

-

Hussite Wars: Introduction

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Man

Hussite Wars: Papal Schism and John Huss

Hussite Wars: The Land

Hussite Wars: Operations to February 1421 Armistice

Hussite Wars: Operations 1421

Hussite Wars: Operations 1422

Hussite Wars: Operations 1423

Hussite Wars: Operations 1424 and After

Hussite Wars: Hussite Wagon Fort Tactics

Hussite Wars: Medieval Weapons

Hussite Wars: Soldiers

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Military Leader

Hussite Wars: Large Map of Bohemia/Moravia (slow: 175K)

Hussite Wars: Jumbo Map of Bohemia/Moravia (extremely slow: 504K)

Hussite Wars: Time Line

Back to Conflict Historical Study 1 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com