The King's death created a power vacuum in Bohemia for several critical months. By August, Prague had sent a list of demands to Sigismund, King of the Germans; although the demands had been mainly authored by the Hussite reformers, the ultimatum had been endorsed by many nobles. Sigismund was uncertain of conditions in Bohemia and delayed his rejection of the demands for four months. During that time the Hussites were busily expanding their fledgling movement, while the dead King's supporters found it increasingly difficult to maintain law and order.

Typical of the rapid growth of the Hussite movement at this time was the religious community at Tabor. The Taborites were a radical faction within the overall Hussite congregation; their extreme puritanical adherence to the precise wording of the Scriptures and spartan lifestyles contrasted markedly with the more moderate reformist movement in Prague. But all Hussites were united in their desire for religious freedom. Mass religious meetings became common.

Such gatherings were held at Tabor on 22 July, near Pilsen on 17 &ptember, and near Benesov on 30 September. Nicholas of Hus and Jan Zizka provided political and military leadership but the dominating religious force was Wenceslas Koranda, a priest from the Taborite community.

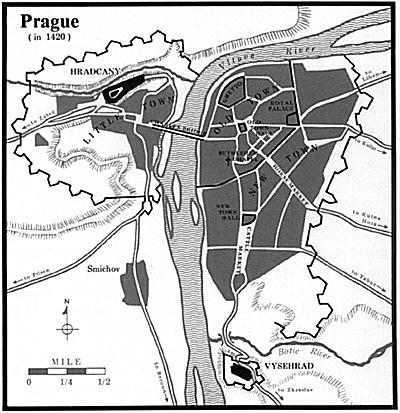

A mass meeting was scheduled in Prague itself for 10 November, 1419. Aware that the Hussites had already taken over the New Town section of the city, Queen Sophia outlawed the meeting for fear it might result in a complete occupation of the capital. On 17 October, the garrisons at Hradcany castle, in Little Town and on the Charles Bridge were strengthened. Orders were to

prevent any Taborite pilgrims from entering the town from the west. Zizka, now a Hussite captain of New Town, grew concerned that a Royalist occupation of the Vysehrad castle with a large body of troops would block all roads into the city and surround the Hussites. On 25 October, with a few Hussite soldiers, he seized the castle with no resistance from the small garrison.

A mass meeting was scheduled in Prague itself for 10 November, 1419. Aware that the Hussites had already taken over the New Town section of the city, Queen Sophia outlawed the meeting for fear it might result in a complete occupation of the capital. On 17 October, the garrisons at Hradcany castle, in Little Town and on the Charles Bridge were strengthened. Orders were to

prevent any Taborite pilgrims from entering the town from the west. Zizka, now a Hussite captain of New Town, grew concerned that a Royalist occupation of the Vysehrad castle with a large body of troops would block all roads into the city and surround the Hussites. On 25 October, with a few Hussite soldiers, he seized the castle with no resistance from the small garrison.

Hostilities

Meanwhile hostilities commenced against the approaching pilgrims. Early in November, near Zivchoust, a Hussite band was butchered by a force of Lord Peter of Sternberg who was in Sigismund's pay. On 4 November, when news of this slaughter reached Prague, the entire population was outraged; demonstrations breaking out not only in New Town, but in more conservative Old Town as well. Ziska and Nicholas of Hus swiftly formulated a military response. On that same day, Hussite troops stormed the garrison on the Charles Bridge, forcing the Royalists to retreat. A Royalist counter-attack failed to dislodge fanatical Hussite soldiers. For the next four days fierce fighting engulfed the bridge and Little Town section of Prague. Finally, on 9 November, with much of Little Town in rubble, a truce was declared. The Hussites were guaranteed freedom of worship in Prague in return for the departure of the pilgrims and restoration of Vysehrad castle to the Royalists.

Incensed by what he considered a monumental blunder by the Hussite leaders in surrendering strategic Vysehrad to the Royalists, Zizka angrily left Prague and went to Pilsen where he had been offered the position of captain of the city by Nicholas Koranda. Pilsen was a critical center of western Bohemia because all major roads from the west passed through it. The Hussites began to turn the town into a bulwark against Sigismund and the armies he was certain to send to restore order.

Royalist forces under Lord Bohuslav of Svamberg had already begun small-scale operations against the outskirts of Pilsen by December. During that month Zizka sortied out of the city to attack the fort of Nekmer to the north. While thus engaged, his troops were set upon by a larger Royalist force; according to one source the Pilseners were outnumbered 2,000 to 300.

Yet, the fanatical religious dedication of the Hussites, combined with seven wagons equipped with siege guns, stunned the Royalists and allowed Zizka's force to escape after inflicting heavy casualties. By itself the battle of Nekmer has no major historical significance, but it did mark the first primitive application of the hradba vozaw (war wagons) that was to be the hallmark of Zizka throughout his military career.

Quickly Svamberg turned on Pilsen and by March his troops had completely besieged the city. Tension was high among the citizens as they were moderate in their practice of Hussitism and they objected to having a radical like Koranda deciding their fate. Additionally they feared what might happen if the Royalist troops succeeded in capturing the city. After considerable debate Zizka agreed to negotiate with Svamberg for a surrender of the city and safe passage for those wishing to leave. The proposal was quickly accepted and on 23 March, 1420, Zizka and Koranda led a small group of Hussites out of Pilsen heading for Tabor under a flag of truce.

Battle of Sudomer

Never intending to honor the truce, a Royalist force of 2,000 knights known as the "Iron Lords" moved to intercept Ziska's pitiful column of 400 poorly-armed foot troops and twelve gun-equipped wagons. On 25 March, near Sudomer, Zizka spotted the knights making their approach march deployed in two columns. Utilizing a pond to cover one flank, Zizka moved the wagons to guard the other flank and rear, placing the infantry on a narrow front in the center. When the Lords attacked in the afternoon, the Hussite alignment forced the knights to dismount and advance on foot. This deprived them of their shock advantage and enabled the Hussites to hold their position despite heavy casualties on both sides and damage to three of Zizka's wagons. As darkness fell the Royalists lapsed into confusion and broke off the engagement. The next morning Zizka reorganized his force and continued to Tabor unmolested.

The battle of Sudomer is significant for two reasons. First, it is the beginning of Zizka's career as a tactrcal leader, with his use of war wagons as an integral element in the defensive fommations of his troops. Second, it made Zizka, now in his fifties, a Bohemian national hero. When he arrived in Tabor on 27 March, he was accorded a triumphal reception by the population. At Sudomer, the myth of the invincible Jan Zizka was born.

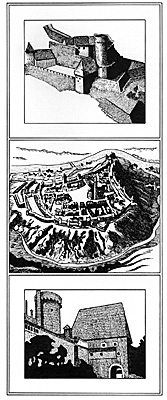

In April, 1420, Zizka was elected one of the four captains of Tabor, and he assumed control over the city's military forces. He rapidly began to mold an effective field army out of the available peasant recruits. To equip the infantry, he ordered new and improved war wagons built, as well as flails, crossbows, and pikes. Cannon, still a novelty, were cast and integrated into the mobile forces. Even though Tabor was located on a steep hill, Zizka ordered a hexagon-shaped double wall anchored by six massive tower bastions to be built around the city to improve its defenses; at the most vulnerable spots the wall was built to three thicknesses, an awesome barrier to any enemy.

Not content just to drill his troops in Tabor, Zizka considered it crucial to train them in actual combat. A raid against Vozice, northeast of Tabor, on 5 April yielded enough horses and weapons to equip a small Taborite cavalry squadron. Later in the month raids were made against Sedlec, Prachatice, and Rabi castle. Although Zizka's avenging troops killed many people in these raids, their puritanical religious beliefs constrained them to seize only military supplies for their own use.

The improvement of the Taborite forces was incredible. In a matter of weeks with limited resources and few men Zizka had created a small, effective army that displayed a sense of organization and discipline unheard of in the medieval armies of the time. When on 16 May Prague sent for help against a Royalist threat, Zizka was ready two days later to march.

These drawings show the architecture of the fortified city of Tabor. Zizka had its defenses strengthened to a greater extent than most towns in Bohemia, although all cities had similar walls surrounding them. A castle was often located nearby or was a part of medieval towns' defensive walls.

These drawings show the architecture of the fortified city of Tabor. Zizka had its defenses strengthened to a greater extent than most towns in Bohemia, although all cities had similar walls surrounding them. A castle was often located nearby or was a part of medieval towns' defensive walls.

During Zizka's time in Pilsen and Tabor events had been unfolding in Prague which were to affect all Bohemia. By early 1420, Sigismund's forces had contained the Hussite movement in Prague. Sigismund appointed Cenek of Wartenberg as regent to replace Queen Sophia. Had it not been for the strong Taborite community, the Hussite revolution might have expired in early 1420.

First Crusade

In March, as the Royalists were successfully besieging Pilsen, a Papal Bull declared the First Crusade against the Hussites. According to one source as many as 150,000 men would eventually take part on the Royalist side. But it took time for the crusaders to organize and move. In the interim the Praguers consolidated their position. Cenek, strongly influenced by Hussite sympathizers, reacted to the announcement of the crusade by declaring himself for the Hussites. His move rallied support from many Bohemian nobles who had previously been undecided in their loyalties. Diplomatic moves were undertaken to gain foreign support and locate a proper king to assume the vacant Bohemian throne; a delegation was sent to Poland to attempt to persuade King Wladyslaw to accept the crown.

The military situation in Prague was mixed. Hradcany castle was held by the Praguers, but Vysehrad was still held by the Royalists as a result of the November, 1419, truce. In early May, 1420, with the assistance of troops from the Orebite faction of Hussites from eastern Bohemia under the command of Lord Hynek Krusina, the Praguers besieged Vysehrad.

However, Cenek of Wartenberg had become outraged by Zizka's raids and changed his allegiance back to Sigismund. On 7 May he arbitrarily turned Hradcany castle over to a 4,000-man Royalist force that had flipped into the city, infuriating the Praguers. Considering it imperative to eliminate the two Royalist bastions in the city, the local militia foolishly tried to simultaneously attack both castles on 8-9 May. Although spirited, both assaults lacked the power to succeed and merely resulted in heavy Praguer casualties. Exhausted, Prague contacted Sigismund and asked for a truce. The King replied by demanding total surrender. Startled by this blatant act of egotism, the city reaffirmed its will to resist. A call went out to the countryside for reinforcements on 16 May.

Responding to the Pope's crusading call, King Sigismund assembled his main army at the Royalist stronghold of Kutna Hora. Meanwhile, Zizka was on the move from Tabor with a 9,000-man army consisting of about 5,000 infantry, a few hundred cavalry, and a large number of war and supply wagons. In the 15th Century it was normal for a medieval army to move at a slow pace of 12-18 miles per day. But Zizka's was no ordinary army; in one day it traversed fifty miles, half the distance to Prague, and arrived at the village of Benesov. There a 400-horse Royalist cavalry unit attempted to halt the advance. A ranking maneuver forced the Royalists to retreat to a nearby monastery and Zizka's force continued its march.

Sigismund ordered his forces to intercept and prevent Zizka from entering Prague. Three columns converged on the Hussites. The main body of 10,000 troops under the command of the Italian Field Marshal Philip de Scolari, Count of Ozora (also known as "Pipo Spano"), marched out of Kutna Hora. A second column of 1,600 cavalry under Wenceslas of Duba sortied out of Hradcany castle, moving south. A third smaller column of 700 troops under Peter of Stemberg moved against Zizka from the southwest. This combined force of nearly 13,000 troops greatly outnumbered the Hussites.

South of Prague, near the village of Porici, Ziska deployed his forces to await the Royalist assault. The war wagons were drawn up into a circle at the top of a hill, with a small moat dug in front of the wagons. Early in the evening of 19 May the Royalists opened their attack. After suffering about fifty casualties Scolari and the other captains recognized the futility of their attack and dusengaged. The next morning Zizka continued his march without further fighting and arrived in Prague later in the day.

Once in Prague, Zizka assumed control over military operations. His first decision was to concentrate available forces against the Royalist castles one at a time instead of trying to maintain two separate but simultaneous sieges. Choosing Hradcany as the first target, he prepared to starve out its occupants while strengthening a moat on the south side of the city to prevent any action from the Vysehrad.

On 22 May Zizka led an ambush of a supply convoy bound for Hradcany, capturing nineteen heavy supply wagons. The next day more Hussites arrived, and siege preparations reached their final stages. At Kutna Hora Sigismund seemed unable to decide on a course of action; with his army he approached to within ten miles of Prague on 24 May, but then quickly returned to Kutna Hora without taking any action to relieve the Royalists in Hradcany.

Ziska opened the main siege against Hradcany on 28 May. In the castle, the lack of supplies was becoming critical. Sigismund responded with more feints by his army; although he was unwilling to do battle, he hoped he could force Zizka into making a tactical mistake. On 12 June Sigismund moved his forces close enough to Prague to prompt Zizka to reform his besiegers into assault formations. As soon as this happened, Sigismund ran a supply convoy into Hradcany castle, then withdrew his army before a battle could be joined. By 14 June it was obvious to Zizka that the siege would not achieve its objective, and he called it off. He then reorganized for the best possible defense of Prague.

But Sigismund was hesitant to attack Prague directly. Instead, he conducted peripheral actions in other parts of Bohemia. On 31 May he persuaded an ally in southern Bohemia, Lord Ulrich of Rosenberg, to move on Tabor. On 16 June the city was besieged. A call went out to Prague for Hussite reinforcements, Zizka responded by sending a 350-man cavalry detachment under the command of Nicholas of Hus. On 30 June the defenders of Tabor and the cavalry reinforcements executed a coordinated two-front counter-attack against the besiegers. The attack caught the Royalists completely by surprise and routed them after inflicting heavy casualties and the JOBS of a large quantity of supplies and siege guns.

Sigismund's army was active in eastern Bohemia. The town of Hradec Kralove was captured in May. This threat did not concern the forces occupied in the combat at Prague, but caused distress among the former inhabitants of the region. Ambrose of Hradec, unable to obtain support from the Praguers, marched alone to the east to gather aid in the countryside to liberate Royalist dominated areas. On 25 June he led an improvised army in a surprise attack which captured the German garrison of Hradec Kralove. Sigismund reacted by besieging the town; unable to force Ambrose to surrender, the Royalists withdrew in mid-July, leaving the city to become a permanent Humite beation.

Siege

Jan Zizka and the Praguers prepared for the anticipated siege of the capital. Zizka's primary concern was to prevent the city from being completely cut-off. As the east side of the city was almost devoid of effective fortifications, he decided to strongly reinforce the Vitkov hill area on the northeast approaches to keep open the vital supply lines to the north and east, and to prevent Sigismund's army from making any surprise marches on the stronghold.

Zizka's anticipation of Sigismund's moves was excellent. On 14 July, 1420, the combined crusading armies of thirty-three nations, numbering perhaps 70,000 horses and a total of 150,000 men, prepared to assault the Vitkov. The Royalist plan was to capture the hill, seal off Prague, then launch a massive all-out three-pronged attack to overrun the capital's walls.

The Vitkov's defenses, even when strengthened, amounted to little more than a moat in front of a reinforced earthen wall. On 14 July, a 9,000-man Royalist cavalry force attacked, approaching from the eastern slopes of the hill. Within minutes the assailants had reached the walls of the last fortifications and reduced the garrison to a mere handful of thirty hard-pressed men.

Unhesitatingly, Zizka ordered the main reserves to counter-attack the Royalists from the south while he personally led a small force to rally the Vitkov. His arrival inspired the defenders to conduct a tenacious defense that halted the Royalist advance. Simultaneously, the main Hussite force threw in its counter-attack deployed in standard Taborite battle formation -- a priest in front carrying the host, followed in order by the archers and the flail- and pike-armed peasants. Thrown off balance by the ferocity of the Hussite onslaught, the crusaders broke and fled. To celebrate the victory the Hussites renamed the hill "Zizkov" to honor their commander.

Large Map of Battle of Prague (slow: 113K)

Although the Royalists had suffered only 500 casualties at the Vitkov battle, Sigismund withdrew his forces, abandoning all further attacks. The crusaders moved into siege positions around the city but Sigismund quickly prohibited the use of siege guns against Prague. At first glance his action seems the height of military incompetence. Yet, Sigismund had sound political reasons for his decision. First, as Prague was a major cultural and commercial center of Europe,the use of artillery would have reduced the city to rubble. Second, if he allowed German crusaders to overrun Prague, no Bohemian city would ever feel safe and Sigismund's already small base of loyal followers in Bohemia would have eroded even further. As he officially assumed the Bohemian crown on 28 July, the sacking of Prague would have been an inauspicious start for his reign.

Two days later, with the crusaders restless and angered by inactivity, Sigismund cancelled the siege. Most of the German soldiers left, only Sigismund's Hungarian troops remained to support the Royalist forces in the country. The combination of Hussite military prowess and Sigismund's vacillating leadership led to the collapse of the First Crusade.

Despite their desire for reform and the Church's declaration of a crusade, most moderate Hussites, primarily in Prague, never gave up attempting a reconciliation with Rome. Unfortunately, the Pope was not so accomodating: Rome's conditions for reconciliation required all but the total dissolution of the movement. Nor was the split with the Church the only rift affecting the Hussites. As the threat of the crusade diminished, the relationship between the extremists of Tabor and the moderates led by the university of Prague became progressively more strained, until the friction created confrontations in the city, resulting in some violence.

Factional Rift

The Praguers resented the zealous Taborites attempting to force their brand of Hussitism on the capital. In mid-August the demands of agriculture slowed a rapidly deteriorating situation. Taborite troops departed Prague to harvest their crops and prepare for the winter. But the rift that had sprouted up between the two factions was very real, and it was destined to become a major element in future wars.

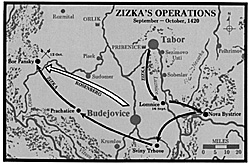

Zizka returned to Tabor with the troops. He was impatient to harass Rosenberg in the south. On 16 September Zizka's force laid a short siege to the strongly fortified town of Lomnice which was captured with surprising ease. For the remainder of the month Zizka attacked Prachatice, Nova Bystrice, and Sviny Trhove.

On 2 October he moved his troops into the Otava valley and besieged the major town of Bor Pansky. To oppose Zizka, Ulrich of Rosenberg, Bohuslav of Svamberg and Henry of Plauen hastily assembled a force of German mercenaries. After the Taborites had occupied Bor Pansky on 12 October, the Royalists arrived. True to form, Zizka retired his forces to a nearby hill and set up a wagon fortress. And true to their form, the Royalists charged up the hill only to be repeatedly repulsed by the defenders. After suffering heavy casualties the Royalties broke

off the action and withdrew. Zizka not only won a battle; the Royalist force attacking him had been diverted from participating in the defense of Vysehrad castle in Prague which was again under siege by the Praguers.

On 2 October he moved his troops into the Otava valley and besieged the major town of Bor Pansky. To oppose Zizka, Ulrich of Rosenberg, Bohuslav of Svamberg and Henry of Plauen hastily assembled a force of German mercenaries. After the Taborites had occupied Bor Pansky on 12 October, the Royalists arrived. True to form, Zizka retired his forces to a nearby hill and set up a wagon fortress. And true to their form, the Royalists charged up the hill only to be repeatedly repulsed by the defenders. After suffering heavy casualties the Royalties broke

off the action and withdrew. Zizka not only won a battle; the Royalist force attacking him had been diverted from participating in the defense of Vysehrad castle in Prague which was again under siege by the Praguers.

Beginning in mid-September, Hynek Krusina led a Praguer army of 12,000 in a siege of Vysehrad. This action should have forced Sigismund to take decisive action to save this critical Royalist stronghold immediately. But again he vacillated, making a series of wholly ineffective feints with his reduced army of 20,000. Lord Vsembera, commander of the Vysehrad garrison, asked to meet with Krusina on 28 October. At that meeting Vsembera agreed to surrender the castle on 31 October if help had not arrived by then. Sigismund still hesitated; it was 31 October before his army arrived at Prague to break the siege. Faced with opponents on two different fronts, the Hussites could have been hard pressed if Vsembera had not scrupulously kept his word.

Sigismund's army attacked, the Vysehrad garrison watched, and the Hussites repulsed the Royalist assault, inflicting 500 casualties. This prompted Sigismund to withdraw his entire army, leaving the battlefield to the Praguers. The jubilant victors quickly tore down the Vysehrad to insure that it would never again be a Royalist stronghold.

There were several interesting aspects to the siege of the Vysehrad. First, it signalled the emergence of the troops of Prague as an effective, independent military force; the victory had been won without the direct aid of Zizka or the Taborites, apparently because Zizka was still very angry over the return of Vysehrad castle to the Royalists in 1419. Second was the impact on Sigismund. Following this defeat he faced the difficult task of keeping his nobles in line and preventing them from deserting to the "winning" side. Not only did Sigismund have to be a military leader, but he also had to conduct delicate political negotiations in the background.

Zizka continued his campaign against Rosenberg into November. Prachatice, which had been previously attacked, was finally seized and resettled by Taborites after all male inhabitants were executed to prevent the town immediately reverting to Royalist control. Zizka's forces cut a wide swath through the region.Wenceslas Koranda escaped from Pabenice castle near Tabor, raised an army, then stormed the fortress that had been his prison since September when he had been captured by Rosenberg's forces. This blow deprived Rosenberg of his most important base camp near Tabor. The cumulative effect of all these Taborite operations brought Rosenberg to his knees. Totally unable to cope with the rapidly moving, hard-hitting troops of Zizka, Rosenberg asked for a truce. An armistice granting the Taborites complete freedom of movement in southern Bohemia until February, 1421, was signed by both sides.

More Hussite Wars

-

Hussite Wars: Introduction

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Man

Hussite Wars: Papal Schism and John Huss

Hussite Wars: The Land

Hussite Wars: Operations to February 1421 Armistice

Hussite Wars: Operations 1421

Hussite Wars: Operations 1422

Hussite Wars: Operations 1423

Hussite Wars: Operations 1424 and After

Hussite Wars: Hussite Wagon Fort Tactics

Hussite Wars: Medieval Weapons

Hussite Wars: Soldiers

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Military Leader

Hussite Wars: Large Map of Bohemia/Moravia (slow: 175K)

Hussite Wars: Jumbo Map of Bohemia/Moravia (extremely slow: 504K)

Hussite Wars: Time Line

Back to Conflict Historical Study 1 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com