To the north, Nicholas of Hus was attempting to improve relations between Tabor and Prague. He joined forces with the Prague troops laying siege to Ricany castle on 24 November. The liaison was effective, compelling Davis of Ricany to surrender on 4 December. But even the victory won by that brief moment of cooperation could not erase the existing tensions between the two communities.

At the end of 1420 the Hussites stood victorious. The Praguers were content with the leveling of Vysehrad and their newly triumphant army. But of greater significance were the accomplishments of Jan Zizka. In a mere eight months he had assembled a mob of peasants, equipped and trained them, then led them as an army on a long series of dramatic victories. There are few other instances in history of a commander accomplishing so very much in so very little time after beginning with so few resources of men and materiel. This improvisational quality was a hallmark of Zizka. If not for him, Sigismund's men would have carried the day at the Vitkov, seized Prague, and crushed the Bohemian Hussites.

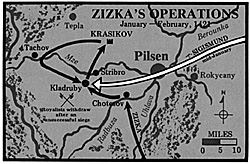

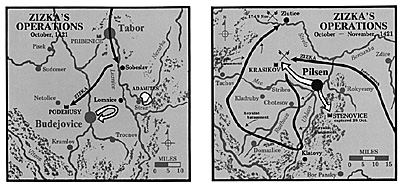

Map at right: The first major Hussite offensive began in early 1421 when Zizka led his army into the Pilsen region. After capturing towns and establishing Hussite communities, Zizka threatened Pilsen itself. Through shrewd diplomacy the Catholics saved their town and became a major impediment to the young Hussite movement.

Map at right: The first major Hussite offensive began in early 1421 when Zizka led his army into the Pilsen region. After capturing towns and establishing Hussite communities, Zizka threatened Pilsen itself. Through shrewd diplomacy the Catholics saved their town and became a major impediment to the young Hussite movement.

Early in 1421 Zizka launched a new offensive in the western end of the Pilsen region. Quickly his troops captured Chotesov, Kladruby, and laid siege to Stribro. Expecting a major fight from Bohuslav of Svamberg, Zizka swiftly besieged his castle of Krasikov before Svamberg could react. When the c astle fell, Svamberg was taken prisoner. The conditions of his nine-month captivity were remarkably pleasant, with the dramatic result that late in 1421, Bohuslav of Svamberg (who had fought for Sigismund and Rosenberg) became one of Zizka's most loyal and reliable allies.

Zizka's brief siege of Tachov, near the Upper Palatinate border aroused Sigismund. Fearing that this new Hussite campaign might cause the loss of the vital Royalist center of Pilsen, Sigismund attacked Kladruby in mid-January. Remarkably, the siege guns of the 12,000 German attackers proved almost ineffectual against the fortifications of the town, while the artillery of the 1,000 Taborite defenders had a deadly effect on the besieging army. His forces extended and exhausted, Zizka sent to Prague for reinforcements to relieve Kladruby. In the face of the common enemy Hussite differences were put aside and William Kostka of Postupice set out with 7,000 men and 320 wagons. The stage was set for a great battle between the Hussites and Sigismund. Sigismund, however, was unwilling to play his part, for on 8 February he ended the siege and withdrew from the region.

Sigismund's fears for Pilsen were not groundless, for Zizka next laid siege to that great city. For four weeks his heavy cannon pounded the fortifications. The gloomy defenders called for a truce. During the negotiations, they astutely offered the Hussites religious freedom in Pilsen, and promised to have Sigismund plead the moderates, case in Rome in retum for the Hussite forces withdrawing. With Zizka's tacit approval, the Hussites accepted these terms and departed, leaving behind them a dangerous center of Royalist power in the heart of western Bohemia. It was a miscalculation caused by a total misunderstanding of the enemy's intentions; a blunder ranking with the return of the Vysehrad to the Royalists in late 1419.

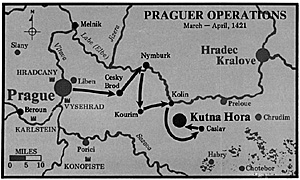

Map at right: Zizka had prevented the capture of the capital in 1420, and this enabled the Praguers to launch an offense in the spring of 1521 that conquered most of the area around the city. This perfad marked the emergence of Prague as an independent military force, surpassing Tabor's army in numbers, but never equalling it in skill or fanaticism.

Map at right: Zizka had prevented the capture of the capital in 1420, and this enabled the Praguers to launch an offense in the spring of 1521 that conquered most of the area around the city. This perfad marked the emergence of Prague as an independent military force, surpassing Tabor's army in numbers, but never equalling it in skill or fanaticism.

While Zizka was active at Pilsen, a force of 1,000 Taborites under Hromadka of Jistebnice occupied the towns of Prelouc and Chotebor in late January. These attacks prompted an immediate response from Royalist Kutna Hora. Mint Master Nicholas led a force which quickly retook Prelouc and then besieged Chotebor. After several days the Taborites asked for terms, agreeing to surrender in return for a safe conduct.

Burned

The Royalists agreed, then promptly burned 700 Hussites on the spot, and carried the rest off to work as slaves in the Kutna Hora silver mines. This Royalist massacre infuriated the Hussites who immediately laid siege to the town of Chomutov in northwest Bohemia. After a three-day siege the village fell and an indiscriminate massacre ensued. 2,400 people were slaughtered in a single retributive act. The murder in Chomutov had a different effect on the Royalists than their treachery in Chotebor had had on the Hussites. Terror swept the Germans and Sigismund's other allies; The Hussites acquired a reputation as harsh, merciless conquerors -- an attribution unfair to the majority of Hussite troops.

On 22 March the combined Hussite armies resumed to Prague after operations in western and northwestern Bohemia eliminated most of the Royalist strongholds posing any threat to the capital and other Hussite centers. Near Prague, only Beroun and Meloik remained in Royalist control. Beroun was besieged on 26 March and surrendered on 1 April. Melnik, seeing the fate of Beroun, quickly surrendered without a fight, thereby clearing the Prague region of Royalist forces.

In April, Zizka left Prague, returning briefly to Tabor to deal with growing political and religious problems. Confident the problems were settled, he resumed to Prague a few weeks later to lead the Hussite armies on a new campaign into eastern Bohemia. However, in his absence a Praguer army had assembled and left the city on 13 April for the Elbe valley region. On 16-17 April, Cesky Brod was assaulted and, despite its numerous fortifications, taken. Following this single impressive victory towns such as Kourim, Nymburk, Kolin, and Caslav chose to peacefully surrender, rather than be razed by conquering Hussite forces.

Next, the Praguers surrounded the major Royalist stronghold at Kutna Hora. Initially, the garrison planned to resist, but as time passed and no reinforcements appeared, the Royalists realized they had no hope of holding out. On 25 April, Kutna Hora surrendered without having fired a shot.

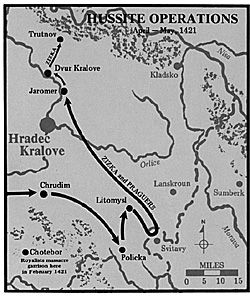

On 26 April, Zizka arrived at Chrudim with his forces to join other Hussites in a successful two-day siege, following quickly with the capture of Policka and Litomysl. In early May the Hussites made a brief foray into western Moravia, rapidly returning to Bohemian soil.

Striking north, Jaromer was overrun and Lord Hynek Cervenohorsky, one of Sigismund's staunch supporters, was captured. Having successfully occupied most of eastern and northeastern Bohemia, the Praguer army prepared to triumphantly return to the capital in mid-May. The campaign had been so impressive that the vacillating Cenek of Wartenberg was persuaded to change loyalties once more and rejoin the Hussite cause; other nobles who were equally impressed, joined him in this conversion.

Zizka and the Taborite army were not through campaigning. Heading north, they captured Dvur Kralove and Trutnov. Wheeling west, Zizka force-marched his troops 100 miles and laid siege to Litomerice, the most important town in northern Bohemia. Near a successful conclusion, Zizka called off the siege so that the Praguers could negotiate a settlement, believing that continued amicable relations with Prague were more important than one captured city. He returned to Prague and sent the army home to rest and refit in Tabor.

During the siege of Litomerice, Zizka forayed with a small detachment and captured a wooden fort near Trebusin, later rebuilding it and naming it Kalich ("Chalice"). At this time he changed his own name to Jan Zizka of the Chalice, and the rebuilt fort would serve as his castle. A utilitarian, unostentatious structure, it well reflected the nature of its master.

Even before the main Praguer army had returned from the spring campaign, a siege had been established against the Royalist bastion of Hradcany castle. Once more, Sigismund was not forthcoming with reinforcements, so in early dune the garrison surrendered. The fall of the castle had major repercussions; it persuaded Konrad of Vechta, Archbishop of Prague, to recognize and accept the Hussite movement.

Diplomacy

Hussite diplomacy was active in the summer of 1421 as the Hussites looked beyond their borders for allies. Silesia and Lusatia, even though they had large Czech populations, made it clear that they rejected the new Bohemian movement. To the east, the situation in Moravia was much different. The Czechs of that country were very sympathetic, but the proximity of Sigismund in neighboring Hungary forced them to maintain silence. The Hussites also continued efforts to locate a suitable replacement for Sigismund; negotiations continued in Poland and Lithuania, with Grand Duke Witold of Lithuania displaying the most favorable interest.

Fortunately for the Hussites, Sigismund at this time was occupied with other troubles. The Turks were invading Transylvania, the Republic of Venice was on the rampage in Dalmatia, and the nobility of the Empire and the Roman Papacy were unhappy with Sigismund's efforts to exterminate the Hussites. Far from being crushed, the Hussites were prospering and multiplying, posing an increasing threat to the Church's authority.

In June, 1421, the Hussites held a Diet at Caslav to decide on a course of action for the new Bohemian leadership. The first act was a vote rejecting Sigismund as the monarch of Bohemia. Next, it was suggested that a regency council be created to replace Sigismund until a new king could be selected and crowned. Jan Zizka attended the Diet. Although a valued member, he did not have a leading role for he was a soldier, not a politician.

A Silesian invasion prompted the Diet to rush Hussite forces under Cenek of Wartenberg to the Nachod area during mid-June. In the face of this response the Silesians retreated across the border without a fight. Wartenberg demanded that no pursuit be made into Silesia. Subordinate commanders who wanted to chase the Silesians dissented vigorously. Many Hussite troops dispersed in protest of the holdfast order. Debate raged in Prague for days before a final decision was made against any border crossing; that policy remained in effect until 1426, although unofficially violated from time to time. Wartenberg, angered by the opposition to his orders, once more turned coat for the fourth time (in fifteen months) and rejoined the Royalists.

At this time, Zizka was active in the west. The rapid conquest of the Royalist castle of Bor resulted in the capture of an important Royalist leader, Meinhard of Jindrichuv Hradec. The Taborites then moved on to besiege the castle of Rabi near Tachov.

Zizka Wounded

While leading his troops in the first assault, Zizka was struck in his remaining good eye by an arrow, and was quickly taken to Prague for medical treatment. As his troops furiously stormed and leveled Rabi, Zizka hung near death for some time.

Gradually his condition improved. However, he was now totally blind and it would be months before he would be able to lead in the same vigorous style that had characterized his earlier campaigns.

In July the continuing political discussion in Bohemia resulted in a synod in Prague to vote on the religious direction of the country. In a series of crucial votes the moderates were victorious, and the extremist Taborite view soundly rejected.

On 10 July, Prague sent out an army under the command of John Zelivsky to aid the menaced cities of Zatec and Louny in the north. The castle of Bilina was quickly overwhelmed in a bloody assault, and the Praguers moved on to the village of Most, investing the town and besieging the castle. More Hussite reinforcements arrived on 22 July. Across the German border, the Meissen margraves viewed this new Hussite campaign with alarm and sent forces to relieve Most. The besieged castle offered Zelivsky a surrender proposal, but he refused to accept anything but total capitulation.

Zelivsky badly misjudged his position: he was remembering the easy victories he had participated in earlier in eastern Bohemia, and failed to realize the radical difference of the present situation. Eastern Bohemia was populated with sympathetic Czechs, the north was peopled with unfriendly natives of German extraction. Further, the Bohemian army in the east was much larger than Zelivsky's, and unlike Zelivsky's Prauger army it did not contain as many mercenary troops who were more difficult to control and inferior to the native Hussite soldiers. Finally, Zelivsky failed to appreciate the critical situation he could face if opposed by the Meissen forces while stil1 tied down in a siege.

There were no "typical" sieges during the Hussite wars. A castle might fall to the first

assault, while some towns held out for days and even weeks as at Zatec in 1421.

There were no "typical" sieges during the Hussite wars. A castle might fall to the first

assault, while some towns held out for days and even weeks as at Zatec in 1421.

Disaster

Disaster struck the Hussites on 5 August. While preoccupied with their siege they were assailed by the Meissen heavy cavalry. Caught in the open, the Hussite infantry was butchered. Zelivsky suffered 400 casualties before he moved the troops back into the wagons where an improvised defense could be established. Night fell and it appeared that the Praguer army might be able to regroup successfully, when inexplicably panic swept through the Hussite force and the entire army disintegrated as frightened men fled into the dark night. It was the worst Hussite defeat up to that point; as in the battle of the Vitkov, psychological factors proved as important as military factors in combat.

By late August the Praguers had recovered sufficiently from their defeat to field another army to oppose the Meissens. This time they chose to put their fortunes with the master -- Jan Zizka. When the margraves heard who they would be fighting they fled back across the border without doing battle. Actually, they ran from a name; Zizka was still recovering from his eye wound.

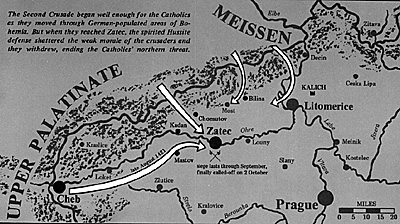

The Second Crusade began well enough for the Catholics as they moved through German-populated areas of Bohemia. But when they reached Zatec, the spirited Hussite defense shattered the weak morale of the crusaders and they withdrew, ending the Catholics' northern threat.

The Second Crusade began well enough for the Catholics as they moved through German-populated areas of Bohemia. But when they reached Zatec, the spirited Hussite defense shattered the weak morale of the crusaders and they withdrew, ending the Catholics' northern threat.

Cardinal Branda, the new papal legate to the Empire, advocated a Second Crusade. It was discussed with increasing urgency at the Imperial Diet in Nurnberg in April, at the meeting of princes in Wesel in May, and at Gorlitz and Mainz in June. At Boppard on the Rhine in July final plans were detailed and fixed. The invasion was set for a border crossing near Cheb on 24 August. The crusading army was even larger than the first; some sources reported its strength at over 200,000, although a figure of 150,000 would probably be more accurate. The crusaders were to be led by the archbishops of Treves, Magdeburg and Cologne, as well as Louis, Count Palatine and Erich, Duke of Saxony. The magnitude of this impending threat forced the Hussites to call a new Diet at Kutna Hora on 21 August to discuss defense plans.

On 28 August the crusaders set out with orders to kill all Czechs except small children. Initially they met little resistance. Within a few days they had reached the town of Mastov, twelve miles from Zatec. In cooperation with the crusaders the Meissens attacked from the north. They conquered Kadan and Chomutov, invested Bilina and laid siege to Ziaka's Kalich castle. But hearing of the approach of a relief army from Prague, the Meissens withdrew and joined the main crusader army near Zatec.

The total Hussite force at Zatec was a mere 6,000 men. Yet, after a week of siege and six full-scale assaults by the crusaders the town stood unconquered. The German forces in the area were angered that Sigismund had not launched a coordinated attack from the east to draw off some of the Hussites. On 30 September, Zatec's defenders made a surprise sortie, inflicting heavy casualties and mortally wounding the already crumbling morale of the crusaders. By 2 October word was received that Zizka was moving on the town with a relief army from Slany. That was all the Germans needed to convince them to pack up and retreat. The withdrawal was hampered by a large fire in the crusaders' tent city. The defenders of Zatec took this opportunity to sortie again and inflict additional heavy casualties in pursuit. The siege of Zatec had cost the crusaders a total of 2,000 dead; but more importantly, the failure of the western attack, before Sigismund had even moved, doomed the Second Crusade.

On 10 October, the Royalists of Leopold Krajir combined with troops of Rosenberg in the south to go on the offensive. The town of Lomnice, under Lord Rohac of Duba, one of Zizka's closest lieutenants, was besieged. Zizka, trying to recruit troops in Caslav (by late 1421 the romance had worn off and recruiting was becoming more difficult for both sides), quickly set out with a relief column. Krajir withdrew but Zizka pushed on across the Vltava River to sieze Rosenberg's Podehusy castle near Netolice, and his castle at Sobeslav.

By the time of these October battles Zizka had largely recovered from his wound, so that he could turn his attention to a local problem in the south. The Adamites, a group of anarchist rebels, had been exiled from Tabor early in 1421. Several hundred strong, they had travelled to the area of Straz on the Nezarka River, settling on a river island. From there this community which practiced nudity, free-love, and murder, took to raiding the local communities. Responding to complaints from the harried citizens, Zizka decided to eliminate the Adamite threat forever. On 21 October he sent 400 men into the area, but the ferocity of the defense had been underestimated. It took additional reinforcements before the Taborites overcame the resistance and slaughtered the Adamites.

Mounted knights attack an early-model wagon fort.

Mounted knights attack an early-model wagon fort.

Zizka's forces during this time were not overwhelming. They were inadequate for any attack on the two Royalist strongholds of the south -- Rosenberg's towns of Krumlov and Budejovice. Nor was there time; Zizka's attention was soon focused on the problem of the Pilsener threat.

On 26 October, the Royalist Pilseners occupied the Hussite fort of Stenovice south of Pilsen, killing all the men. From there, under the guidance of Krusina of Svamberg, Bohuslav's brother, they went on to besiege the Krasikov castle. Zizka and his new ally Bohuslav force-marched 120 miles to meet the threat. Early in November brother met brother in the opposing armies. Although outnumbered, Zizka's skill was all that was needed to carry the day and relieve the castle. The Taborites left the region to head south to Klatovy in an attempt to avoid the Royalists who had been reinforced with troops from Henry of Plauen.

As the Royalists gained strength they increased their harassment' of Zizka's flanks. With only a 2,000-man force the Hussite commander was forced to remain constantly on the run, following an evasive course that eventually led back to the north.

By 17 November, Zizka decided to make a stand near Zlutice on the steep 800-foot-high Vladar hill by placing his troops in the standard war wagon fortress position. Day after day the Royalists assaulted his lines without success despite the heavy casualties both sides suffered. Yet, the Royalists were content to simply outlast the Hussites; Zizka and his troops were low on supplies and suffering greatly from the new winter's cold nights.

Night Attack

On 19 November, Zizka formed his soldiers for a night counter-attack, a difficult maneuver under any circumstances. In typical Taborite fashion the charge was a success, catching the Royalists by surprise and throwing them into total confusion. This action allowed Zizka and his army to continue their march without further fighting and was one of the first times that the Hussite commander had utilized an offensive operation to save a deteriorating defensive position.

By late September Sigismund had readied his forces. Philip Scolari again was at the head of a Hungarian army of 60,000 men, which included a concentration of 23,000 cavalry. During the first half of October, Scolari moved into Moravia, with Sigismund joining him shortly therafter. Instead of driving straight into Bohemia, Sigismund insisted on waiting for additional reinforcements. Since his army already outnumbered the Hussites, this was a strategic blunder. The Hussites were badly divided -- the Praguers were battling the crusaders near Zatec and Zizka was fighting in the south.

Zizka's operations following the Catholics' abortive attack in the north (before Sigrsmund invaded from the east) defeated Royalist attempt' to regoin the initiative against thc Hussites. After securing the Tabor region againgst Rosenberg, Zizka moved on to strike the Pilseners in late 1421, adding more towns and territory to the Hussite movement, but unable to seize Pilsen itself.

Zizka's operations following the Catholics' abortive attack in the north (before Sigrsmund invaded from the east) defeated Royalist attempt' to regoin the initiative against thc Hussites. After securing the Tabor region againgst Rosenberg, Zizka moved on to strike the Pilseners in late 1421, adding more towns and territory to the Hussite movement, but unable to seize Pilsen itself.

By the time the first tentative Hungarian cavalry thrust was made into Bohemia it was too late. The Praguers had moved to the east as early as 14 November, laying siege to the town and castle of Malesov (south of Kutna Hora) and capturing both five days later. On 22 November, Hungarian cavalry crossed the border and seized Policka, slaughtering 1,300 citizens. On 29 November, Zizka had freed himself in the south and passed through Prague with his army on the way to Kutna Hora. By early December the bulk of Sigismund's army had crossed into Bohemia north of Jihlava and set course for Kutna Hora.

Zizka arrived in the city on 9 December before the Royalists. Inexplicably it took Sigismund's men twenty days to cover fifty miles against little or no opposition from local militia. During that time Zizka was gathering reinforcements and strengthening the defenses of not only Kutna Hora but also Caslav. The extra time he had to fortify and consolidate his positions was crucial to the outcome of the impending battle. At long last Sigismund arrived on 21 December, approaching the city from the west. Leaving a small detachment of troops with the town militia, Zizka took his main forces out to straddle the road approaches on the western outskirts of Kutna Hora.

Philip Scolari, a remarkable tactician and military commander, may not have had the skill of Zizka, but he was unquestionably the best man that the Royalists ever sent into the field to face the Hussites. His plan for attacking Zizka's 12,000 men at Kutna Hora was a brilliant maneuver of incredible sophistication for the medieval period. He spread his cavalry out in front of the Hussite lines, and throughout the day they repeatedly assaulted. Zizka's troops and artillery inflicted heavy casualties, but Scolari expected this.

While Zizka's attention was riveted to the front, Scolari swept troops around the right flank at dusk and occupied Kutna Hora when traitors opened the city gates and butchered the small defending force. Before Zizka could react Scolari swept the Hussite's left flank and completed the pincer movement that completely surrounded Zizka and his forces by nightfall.

Yet, as brilliantly as Scolari had performed, Zizka remained the master. During the night Zizka ordered his troops to move surreptitiously up to the center of the Royalist lines opposite the camp of Sigismund. At dawn on 22 December the Hussites smashed into the Royalist lines, panicking Sigismund's retinue into night. This superbly coordinated attack was highlighted by the war wagons executing a fire/movement operation demonstrating the principles of self-propelled assault artillery at its very best. Breaking free, Zizka headed his troops to a temporary defensive position on Kank hill to await the anticipated Royalist pursuit. But the Royalists were too confused and disorganized to pursue, and the Hussites moved on to Kolin unmolested at the end of the day.

After that battle the contrasts between Ziska and Sigismund were vividly illustrated. Following the Hussites to Kolin, Sigismund decided to go into winter quarters in the region and dispersed his troops. Zizka, on the other hand, immediately went north and spent two weeks recruiting fresh troops and integrating them into his army.

More Hussite Wars

-

Hussite Wars: Introduction

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Man

Hussite Wars: Papal Schism and John Huss

Hussite Wars: The Land

Hussite Wars: Operations to February 1421 Armistice

Hussite Wars: Operations 1421

Hussite Wars: Operations 1422

Hussite Wars: Operations 1423

Hussite Wars: Operations 1424 and After

Hussite Wars: Hussite Wagon Fort Tactics

Hussite Wars: Medieval Weapons

Hussite Wars: Soldiers

Hussite Wars: Jan Zizka: The Military Leader

Hussite Wars: Large Map of Bohemia/Moravia (slow: 175K)

Hussite Wars: Jumbo Map of Bohemia/Moravia (extremely slow: 504K)

Hussite Wars: Time Line

Back to Conflict Historical Study 1 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com