Through the mists of early dawn, the French infantry clambered

up the steep, boulder-strewn, gorse covered slopes. Within just a

couple of hours the 2nd and 6th Corps had been driven back to the

foot of the mountain having suffered over 4,000 casualties. Massena

knew that his decision to attack Busaco had been illjudged.

Through the mists of early dawn, the French infantry clambered

up the steep, boulder-strewn, gorse covered slopes. Within just a

couple of hours the 2nd and 6th Corps had been driven back to the

foot of the mountain having suffered over 4,000 casualties. Massena

knew that his decision to attack Busaco had been illjudged.

He was therefore left with the alternatives of retreating back to Aimeida or of trying to find a way around Wellington's position. Massena was not the kind of man to give up at the first set-back. By noon the following day his cavalry scouts had discovered a road which ran around the north of Busaco, from Mortagoa, through the Caramula mountains to Sardao on the main Oporto to Lisbon highway. By late afternoon the first French units were on the move towards Mortagoa, and Wellington, seeing that his position would soon be turned, abandoned Busaco and marched southwards towards Lisbon.

So far throughout the campaign, the French had found that the Portuguese inhabitants of the towns and villages on the line of advance had evacuated their homes before the arrival of the invaders. Now they were moving upon Coimbra, the country's third largest city. Massena could not believe that the British would expose this rich, educational and spiritually important centre to ravage without another fight.

Coimbra

Yet the Army of Portugal found Coimbra as deserted as the rest of the countryside. For the first time since they had entered Portugal the French troops found a town full of food. When they marched into the city the French units broke ranks and went on the rampage. In two orgiastic days, Massena's men wasted food that would, with care, have lasted two months.

Massena remained at Coimbra for two days. Part of the reason for this delay was due to the fact that his army was out of control, running riot throughout the city, but he also needed time to consider his strategy. He never imagined that the allied commander would abandon such a large place to its fate. It now appeared that, despite the victory at Busaco, the British army was in full retreat for the coast. Reynier and Montbrun (who commanded the cavalry) urged Massena to pursue the Anglo-Portuguese army immediately.

Ney and Junot, however, wanted time to allow the troops to recover from the hard marching and fighting of the previous few days. They suggested, as they had before Busaco, re-opening communications with Almeida and waiting for reinforcements. They argued that a hasty pursuit might bring the Army of Portugal up against the allied army drawn up in another strong defensive position. The French troops would have little enthusiasm for another battle so soon.

The same reasons that compelled Massena to fight at Busaco drove him from Coimbra On 3 October, Montbrun's cavalry led the advance across the Mondego. Eleven days later, and less than thirty miles from Lisbon, Massena halted once again - as he stared up at the impenetrable range of hills and forts of the Lines of Torres Vedras.

Defenses

Massena's indomitable spirit had pushed the Army of Portugal on through the rugged mountains of Northern Portugal and had driven his men up the steep slopes of Busaco. He had then forced them to march on after bloody defeat, but he now quailed at the sight of Wellington's secretly constructed defences. These stretched from the Tagus to the sea, and barred the road to Lisbon. Massena's last great decision of his campaign in Portugal now confronted him. If he broke through the Lines, he was just three marches from securing his objective.

He could then hope to retire (he was then fifty-two and looked it), secure in his fame and not inconsiderable fortune. However, his army had been beaten once already, and if it was to be beaten again it might break and shatter. Stranded hundreds of miles deep within a hostile country, the Army of Portugal might succumb to the severest defeat yet suffered by any of the armies of Napoleon. Massena's reputation and his chances of comfortable retirement would be destroyed.

As before Busaco, Massena called together his senior officers. Junot wanted to attack, Ney and Reynier urged caution -- their army was weak, the enemy's position was strong. Better to retreat than suffer defeat. Massena would not go back but he dared not go forward. He settled down before the Lines of Torres Vedras to await reinforcements and the coming winter.

As before Busaco, Massena called together his senior officers. Junot wanted to attack, Ney and Reynier urged caution -- their army was weak, the enemy's position was strong. Better to retreat than suffer defeat. Massena would not go back but he dared not go forward. He settled down before the Lines of Torres Vedras to await reinforcements and the coming winter.

Winter

The winter came but not the expected reinforcements. The Army of Portugal grew weaker in both numbers and spirit as each day passed. In the Spring of 1811, Massena bowed to the inevitable and turned his army round and marched back to Spain. He had lost around 25,000 men.

Massena's march by way of Viseu cannot, in

all justification, be condemned. He made the only

decision that he could, based on the information

available to him at the time. [1] The only possible

criticism of Massena at this stage is that he failed to

reconnoitre his intended route. He had a

powerful cavalry force - certainly superior to his

opponent - and plenty of time available to him.

In his defence it must be stated that the Portuguese Ordenanza were already attacking French piquets and patrols. [2] In addition the Anglo-Portuguese army, of uncertain strength, was known to be waiting over the horizon.

The march via Vseu added two days on to the

journey and inflicted much material damage upon the

artillery and wheeled transport. It did not, however,

compromise the campaign to any serious degree.

Massena's decision to attack at Busaco proved,

however, to be a disastrous and irreversible mistake.

Firstly he failed to hasten to the front on the 25

September and even on the following day his

movements were marked by a distinct lack of

expedition. As a consequence of this his army had

been halted for two days before he arrived at

Busaco. Time was now against him. His troops were

hungry ('The soldiers discover a few potatoes and

other vegetables' [3] ) and demoralised by the depopulation of the countryside.

The memory of the heavy defeat at Busaco undoubtedly

influenced Massena's decision not to attack the Lines of Torres

Vedras. Certainly, his corps commanders had no stomach left for a

fight. 'Our heavy losses at Busaco had chilled the ardour of

Massena's lieutenants,' wrote Baron Marbot, 'and bred ill-will

between them and him, so that now all were trying to paralyse his

operations, and representing every hillock to be a height of Busaco'.

[4]

Massena himself was sufficiently discouraged by the Busaco

affair, or over-awed by the strength of the Lines. He reported to

Napoleon, 'The Marshal Prince d'Essling has come to the conclusion

that he would compromise the army of His Majesty, if he were to

attack in force lines so formidable.' [5]

His aide, Pelet, agreed with Massena. '(I)nstead of the

undulating accessible plateau that we had been told to expect, we

saw steeply scarped mountains and deep ravines, a road passage

only a few paces broad and each side, walls of rock crowned with

everything which could be accomplished in the way of field

fortifications garnished with artillery. Then at last it was

plainly demonstrated to us that we could not attack the

Lines of Montechique with the 35,000 or 36,000 men that still

remained of the army.' [6]

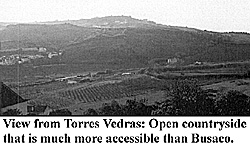

There is, in fact, no place along the twenty-odd miles of the

Lines that compares in strength with that of Busaco, and it is

surprising that Massena made no attempt whatsoever to penetrate them. Marbot

again, 'it seemed to us that the ground was sufficiently irregular to

conceal the movements of a portion of our army, and that by

employing one corps to make a feint on the front while the other two

pushed real attacks on the weakest points of the lines, they would

find the English troops too widely scattered or at any rate with their

reserves at a considerable distance from the points attacked....We

thought that at some point of their vast extent it would be easy to

pierce the English lines, and an opening, once made, the enemy's troops would be in some cases a day's journey from the opening.' [7]

Massena, who had been reckless at Busaco when he should

have been circumspect, was cautious at Torres Vedras when

boldness might have succeeded. That, however, is pure speculation.

It is certainly possible that Massena was correct in his decision not to

attack the Lines. Although Wellington had proven strong in defence, he had shown no inclinations to attempt any offensive operations. Even if he had been defeated, Massena might have been able to hold his ground in front of the Lines.

Massena effectively lost the campaign at Busaco. That single error was possibly the greatest mistake of his military career. Having examined Busaco and the ground around the Lines, I

firmly agree with Marbot.

He believed that 'if the position (Busaco} had been turned, the enemy would have retired upon Lisbon, and our army, in full strength and ardour, would have attacked the lines on

its arrival, and certainly have carried them.' [8]

Notes

[1] There was in fact a second alternative route which ran

through Castello Branco. This was used by Junot in the first invasion of Portugal in 1807. The road was extremely poor and all but impassable for heavy artillery, and was not a serious option in 1810. No doubt Junot, or one of his subordinates advised Massena against considering this route.

More Portugal

French Invasion of Portugal Part 1: Wellington's Plans for the Defence of Portugal

He needed a quick victory to restore their

fervour and he threw them at Busaco after only the

briefest of reconnaisances. The sun sets behind the

Serra de Busaco casting the eastern facing slopes

into shadow at a relatively early hour. Massena had

lost the sight of one eye in a hunting accident

and Wellington had concealed his troops behind the

crest of the ridge with skirmishers pushed down the

forward slopes. Massena could not have had any real

idea of Wellington's dispositions, but he must have

seen how severe the climb up the mountain would be.

His attack was reckless in the extreme. That he failed

to even investigate whether or not the position could

have been turned before the battle, was an equally

remarkable error of judgement. After taking such pains

to avoid the defences at Ponte de Murcella, his

decision to then attack an equally formidable position

at Busaco is hard to justify.

He needed a quick victory to restore their

fervour and he threw them at Busaco after only the

briefest of reconnaisances. The sun sets behind the

Serra de Busaco casting the eastern facing slopes

into shadow at a relatively early hour. Massena had

lost the sight of one eye in a hunting accident

and Wellington had concealed his troops behind the

crest of the ridge with skirmishers pushed down the

forward slopes. Massena could not have had any real

idea of Wellington's dispositions, but he must have

seen how severe the climb up the mountain would be.

His attack was reckless in the extreme. That he failed

to even investigate whether or not the position could

have been turned before the battle, was an equally

remarkable error of judgement. After taking such pains

to avoid the defences at Ponte de Murcella, his

decision to then attack an equally formidable position

at Busaco is hard to justify.

[2] J. Gurwood, The Dispatches of Field Marshal, the

Duke of Wellington, Vol VI, pp 419 20, 9m September 1810

[3] Massena to Berthier, 22 September 1810. Sir Charles

Oman, History of the Peninsular War, Vol. III pp. 352-3.

[4] J. Marbot, The Memoirs of Baron de Marbot, 1892,

p.433

[5] Massena to Napoleon, 22 November 1810 Oman, Vol.

III, p.445

[6] J. Pelet, The French Campaign in Portugal, 1810-11,

1973, p. 323. These figures are not valid. At Busaco the Army of Portugal totalled 64,947 (Archives Nationales, cited in Oman, Vol. III, p. 543, Appendix Vlill. In the battle they lost 4,487 men exclusive of missing. Even assuming 10% on the sick list and a large number reported missing, Massena must have arrived before the Lines with around 50,000 men.

[7] Marbot, pp. 434-5.

[8] Ibid., p. 433

Part 2: Wellington's Plans for the Defense of Portugal

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 1

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 2

Introduction

The Military Geography of Portugal

The Situation in 1810 and Fortresses

The Devastation of the Countryside and Footnotes

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 21 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com