On 17 April 1810, Marshal Andre Massena, Prince of Essling, was

placed in command of 'L'Armee de Portugal' and instructed to capture Lisbon and drive Wellington's army into the sea. At various times during the subsequent campaign he was obliged to make a number of crucial decisions. As Massena ultimately lost the campaign it would seem that he made the wrong decisions. But did he?

Napoleon had told Massena that "I do not wish an immediate entry into Lisbon, as I could not feed the city with its immense population which lives on imported food. He should employ the summer months taking Cuidad Rodrigo and Almeida. There is no need to hurry. He should proceed methodically." 2

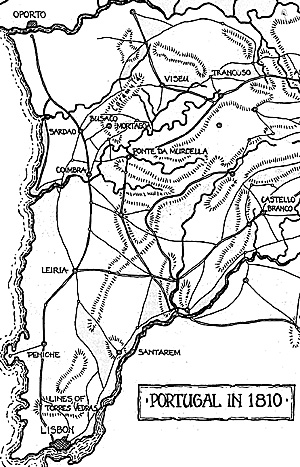

Consequently, it was not until 15 September with the frontier fortresses of Cuidad Rodrigo and Almeida safely in French hands that the invasion began. Until this point, Massena had not been called upon to make any significant decisions. The capture of the two fortresses had been left to his most capable

subordinate, Marshal Ney, but now he had to decide which route to take to Lisbon. It was a decision of paramount importance.

The only apparent alternative

route was a very poor, mountainous road

which went through Pinhel and Viseu,

by-passing the Ponte da Murcella, and

then on to join the main road at Coimbra.

A possible third alternative was to divide

his army in two, sending one part to hold

down Wellington at Ponte da Murcella

whilst the other part turned the British

position by marching via Viseu. It would

thus be able to fall upon Wellington's

rear.

To aid him in making his

decision, Massena had thirty renegade

Portuguese officers on his staff. He also

had the help of Junot and the officers

and engineers of his corps that had

invaded Portugal less than three years

earlier. 5 Ye the information that he received proved completely misleading. 'The presence of the Portuguese officers was particularly disastrous for us,' wrote Pelet, 'Without making a dismal listing of all the errors transmitted to us in the information that the Prince or I requested, I will cite only one example.

On 15 April, an engineer captain who had taken part in the campaign of

1807 gave me the following information at Cuidad Rodrigo. I copied it word for

word in my Journal the same day. 'Beyond the confluence of the Zezere the

country becomes flat. The bed of the Tagus becomes wider. There are only

scattered hills and everything is very approachable . . . It is the same all the

way to the sea...accessible to all armies, and adequate for marching or

manoeuvring in any direction from the Tagus . . .' From this vague description how could we anticipate the inaccessible positions and the rock walls? (of the Lines of Torres Vedras) . . .

We were even less fortunate in what we had been told about the military topography of Portugal, about the inaccessibility of the Serra de Estrella and the banks of the Zezere, the nature of the Tagus and the country in general, the roads and the positions of Bussaco and

Murcella. . .We had been told that some good roads extended on the right bank of the Mondego through open, flat country up to Coimbra, and that by this means we could turn the position of Ponte da Murcella. 6

From this it is clear that Massena, though he knew that the

Celorico road was the best and most direct route to Lisbon, believed that he

would encounter no particular difficulty if he took the road through Viseu. By

following this road he would force the AngloPortuguese army to abandon its

position forcing them to battle on ground that was not of their choosing. The

consideration of dividing his army was quickly dismissed. 'Double lines were

rejected because of the size of the army as well as the nature of the country,'

said Pelet, 'The enemy would be able to throw himself on either line or

between them as we approached Lisbon, where the ground became less

difficult.' 7

The maps with which Massena had been supplied did nothing to counter this view. 'We were in effect without maps,' recorded Pelet, 'since that of Lopez, in spite of its large scale, was poorly marked, the roads and rivers horribly drawn and the terrain even more poorly represented. There was also a poor little map by a Portuguese major, not to mention several even

more defective ones drawn on the previous maps. A few private drawings had been given us, but they could not be of any help, they showed even more errors, for their scale was larger. 8

The Army of Portugal therefore left Almeida and marched to Viseu.

Very shortly after leaving the main Celorico road, it became apparent that

Massena had made a mistake. 'After passing the little town of Trancoso . . .

all the countryside is mountain and rock,' remarked one of Junot's artillery

officers, Colonel Noel. 'There is no road, only a stony, narrow, dangerous

track, which the artillery had all the pains in the world to follow without

meeting accidents. It is all steep ups and downs.

I had to march with a party of gunners ahead of me, with picks and

crowbars to enlarge the track . . . The guns were almost always

abandoned to themselves; we did not know what road to follow, having

no-one to give us information but a few infantry stragglers, who had

themselves lost their way.' 9 When Massena reached Viseu he informed Napoleon of his predicament. 'It is impossible to find worse roads than

these; they bristle with rocks; the guns and train have suffered severely,

and I must wait for them. . . Sire, all our marches are across a desert;

not a soul to be seen anywhere; everywhere is abandoned.' 10 The 2nd Corps led the French march from Viseu and, on 24 September, it encountered the allied rearguard for the first time in the plain before the town of Mortagoa, fourteen miles north of Busaco. The rearguard held its ground until the main body of the 2nd Corps arrived the following day. It then retreated to the village of Moura at the foot of the Serra de Busaco where it again made a stand. Ney, with the 6th Corps, joined the 2nd Corps and Wellington withdrew the rearguard up the slopes of the mountain where further allied troops were posted. By this time, there was only a few hours of daylight left and Ney decided not to attack the heights. Massena did not ride up to the front even though he must have heard the cannon firing throughout the afternoon. He had been informed by Reynier that Wellington was standing at bay on the Busaco ridge.

It seemed apparent to Ney that Wellington would not be easily dislodged from an obviously strong position, and he did not attack as requested. Instead, Reynier wrote to Massena: 'It is necessary to climb a steep slope to attack the Anglo-Portuguese. Moreover, I am not in a position to oppose the enemy artillery. I impatiently await the role that you will assign to me. 13

It was becoming increasingly evident to Massena that his presence at the front had now

become essential. He left Mortagoa in the afternoon, arriving at Ney's headquarters at

around 5:00 p.m.

Together, the two marshals made a reconnaissance of the allied positions in the fading light of evening. Wellington was in a strong position and apparently prepared to fight, and so Massena was now faced with the second major decision of the campaign.

Massena's instinct was to attack but he decided to call a council of

war. That evening he invited Friron, his chief of staff, Eble, who commanded

the artillery, Lazowski of the Engineers, and his three corps commanders to

discuss the situation. Only Reynier and Lazowski were in favour of an attack,

all the others opposed an assault upon such a formidable position. Ney

suggested a withdrawal to Viseu from where they could threaten Oporto or

retire upon Almeida and Cuidad Rodrigo to await reinforcements.

Massena quickly dismissed this negative line of reasoning. 'The

Emperor has ordered us to march on Lisbon, not Oporto, and he has his

reasons.' he told Ney, 'The capture of Lisbon ends the struggle while that of

Oporto only prolongs it without any termination. ' He also reasoned that that

Wellington would still be able to block the French if they marched upon

Oporto, as the allies had a direct route from Coimbra to Oporto. They could

therefore be there ahead of the French.

Regarding Ney's suggestion of retiring to the protection of Almeida

and Cuidad Rodrigo, Massena answered that ' there will always be time to

think o that after sustaining a defeat...The worst result of a defeat would be to

retire our base of operations behind the Coa between Almeida and Cuidad

Rodrigo . . . The victory on the other hand, would force the British to

evacuate the country between the Mondego and Tagus. 14 Friron and Eble

suggested making an attempt to turn Wellington's flank. But Massena

ignored this sound advice. 'You are of the Army of the Rhine, you like to

manoeuvre,' Massena replied contemptuously, 'This is the first time that

Wellington appears disposed to offer battle. I will profit by the occasion. 15

That night, Massena dictated his orders for the attack.

End of Part 1

More Portugal

French Invasion of Portugal Part 1: Wellington's Plans for the Defence of Portugal

NOTES

1 Charles Oman, A History of the Peninsular War, 1902-30, vol. III, pp.200-206.

Massena's force was to consist of the 2nd, 6th and 8th army corps and the troops of General Kellerman and Bonnet that were occupying the provinces of Toro, Palencia, Valladolid and Santander. An unattached division was under General Serras. Massena was also promised the use of

the 9th Corps which was a recently formed body made up of newly recruited 4th Battalions of regiments already serving in Spain. This whole force numbered some 138,000 officers and men. However, Kellerman and Bonnet were fully occupied with maintaining order in their respective districts and the 9th Corps did not arrive at Vitoria until September, after the invasion had

begun. The effective strength of the available field army was therefore no more than 86,000 (2nd Corps, Reynier - 20,000 all ranks; 6th Corps, Ney - 35,000; 8th Corps, Junot 26,000; Reserve Cavalry Corps, 5,000; 12,000 sick).' 1

Massena's force was to consist of the 2nd, 6th and 8th army corps and the troops of General Kellerman and Bonnet that were occupying the provinces of Toro, Palencia, Valladolid and Santander. An unattached division was under General Serras. Massena was also promised the use of

the 9th Corps which was a recently formed body made up of newly recruited 4th Battalions of regiments already serving in Spain. This whole force numbered some 138,000 officers and men. However, Kellerman and Bonnet were fully occupied with maintaining order in their respective districts and the 9th Corps did not arrive at Vitoria until September, after the invasion had

begun. The effective strength of the available field army was therefore no more than 86,000 (2nd Corps, Reynier - 20,000 all ranks; 6th Corps, Ney - 35,000; 8th Corps, Junot 26,000; Reserve Cavalry Corps, 5,000; 12,000 sick).' 1

The first, and most obvious, route

was along a major, paved road that ran

from Almeida by Celoricol Ponte da

Murcella and Coimbra. It was a relatively

good road compared with many of the

Portuguese roads of the day. However, it

was known at Massena's headquarters

that Wellington had built a line of

earthwork redoubts at the Ponte da

Murcella 3, where there was a 'long

commanding bare ridge between the Alva

and the Mondego, a distance of six

miles, each flank falling steep to the

deep ravines of those rivers'. 4 It offered

an excellent defensive position to dispute

the river crossing. The bridge was also

mined.

The first, and most obvious, route

was along a major, paved road that ran

from Almeida by Celoricol Ponte da

Murcella and Coimbra. It was a relatively

good road compared with many of the

Portuguese roads of the day. However, it

was known at Massena's headquarters

that Wellington had built a line of

earthwork redoubts at the Ponte da

Murcella 3, where there was a 'long

commanding bare ridge between the Alva

and the Mondego, a distance of six

miles, each flank falling steep to the

deep ravines of those rivers'. 4 It offered

an excellent defensive position to dispute

the river crossing. The bridge was also

mined.

The following morning allied troops could be seen moving around

along the crest of the ridge. A few deserters and captured stragglers

revealed that Wellington had concentrated a large body of troops upon the

mountain. 11 Ney sent a message to Massena informing him of the situation. Ney's aide, a Colonel D'Esmenard, arrived at Massena's headquarters at Tondella, twenty-two miles to the rear at about 10:00 a.m. Upon receipt of Ney's letter, Massena set off for the front, reaching Mortagoa at noon. 'I have arrived at Mortagoa an I have decided to stop for a time,' he wrote to Ney,' I think that you should continue your march, pushing them towards Luso. If they hold, please send one of my officers who is in your vicinity, and I will join the 6th Corps. 12

The following morning allied troops could be seen moving around

along the crest of the ridge. A few deserters and captured stragglers

revealed that Wellington had concentrated a large body of troops upon the

mountain. 11 Ney sent a message to Massena informing him of the situation. Ney's aide, a Colonel D'Esmenard, arrived at Massena's headquarters at Tondella, twenty-two miles to the rear at about 10:00 a.m. Upon receipt of Ney's letter, Massena set off for the front, reaching Mortagoa at noon. 'I have arrived at Mortagoa an I have decided to stop for a time,' he wrote to Ney,' I think that you should continue your march, pushing them towards Luso. If they hold, please send one of my officers who is in your vicinity, and I will join the 6th Corps. 12

Part 2: Wellington's Plans for the Defense of Portugal

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 1

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 2

Introduction

The Military Geography of Portugal

The Situation in 1810 and Fortresses

The Devastation of the Countryside and Footnotes

2 La Correspondence de Napoleon 1er, XX 16,519, Napoleon to Berthier, 29 May 1810

3 'While we were ignorant of the enemy's most important works, we knew some details about his first line of defence. On the most direct road to Coimbra, between the Mondego and Serra de Estrella, they had carefully fortified the position of Ponte da Murcella, which was already very formidable, rendering it almost inaccessible.' J.

PeletThe French Campaign in Portugal 1810-11,1973, p.138.

4 J. Burgoyne, Life and Correspondence of Field Marshal Sir John Burgoyne, vol. 1, p.107.

5 '...we should have had an inexhaustible source of excellent information. Since this was the third expedition to Portugal within three years, we had generals, staff officers, engineer officers and an entire army corps who had taken part in the first campaign.' Pelet, p.136.

6 Pelet, pp.136-8.

7 Ibid., p.140.

8 Ibid., p.55 and p.135

9 J. Noel, Souveniers Militaires, pp.112-3.

10 Massena to Berthier, 22 Sept.1810, quoted in Oman, vol. lIl, pp.352-3.

11 Ney to Reynier,10:30 a.m., 26 Sept.1810, quoted in W. Napier, History of the War in the Peninsula, 1864, vol. lil. pp.515, Appendix XIIl Section III.

12 Massena to Ney,12:00 p.m., 26 Sept.1810, quoted in JW Fortescue, History of the British Army, 1906-20, vol. VIII, pp. 513 and 525.

13 Ibid., Reynier to Massena, 2.00 p.m., 26 Sept.1810

14 Koch, Memoirs de Massena, vol. VIII, ppl91-2; quoted in G.Chambers, Wellington's Battlefields Illustrated: Bussaco 1810, 1911, p.184.

15 Ibid.

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 20 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com