THE PORTUGUESE ARMED FORCES

In addition to re-building and re-equipping the regular army, Wellington intended to revive the militia and to order the ancient call to arms of the Ordenanza. 'If arms can be supplied for the militia,' he advised the Secretary of State for war in January 1810, 'there is no doubt that there will be in this country not less than a gross force of 90,000 men, regularly organised, besides the whole armed population of the country and the British army.'[2] The population of Portugal in 1809 was calculated as including 1,250,000 males capable of carrying arms, and so there should not have been a problem in recruiting for the armed forces.[3]

Military service was unacceptable to most young men and it was found necessary to enforce conscription with very severe penalties meted out to those who attempted to desert, 'the officers and soldiers of the militia, absent from their corps, are liable to penalties and punishments.' Wellington told Britain's representative on the Portuguese regency Council. 'First, they are liable to the forfeiture of all their personal property, upon the information that they are absent from their corps with out leave; secondly, they are liable to be transferred to serve as soldiers in the regiments of the line, upon the same information; and lastly, they are liable to the penalties of desertion, inflicted by the military tribunals.'[4]

Recruiting was organised on a local basis by the Captain-Major (Capitaos Mor) of the Armed Inhabitants, or Ordenanza, of each district. These officials were either resident manorial noblemen of towns or villages, or in the cities or where the Iocal lord did not reside on his property the position of Captain-Major was taken by the chief-magistrate. Each regiment of the regular army was allocated its own recruiting area. When recruits were required the Captain Major would be instructed to collect together the requisite number of men from his district and send them off, under an armed escort of the Ordenanza, to the regiment. The militia was recruited in much the same way.

All the remaining males between the ages of 16 and 60 in the district were numbered by the Captain-Major and divided into companies of 250 men each. Each company was led by a captain selected by the Captain Major. The executive officer responsible for organising the companies under the command of the Captain-Major was the Sargento Mor who acted in the same capacity as a major would in the regular army. Every company was divided into squads of twenty-five men each, the squad being commanded by a corporal. The effective strength of each company was, one captain, one ensign, one sergeant, an officer similar to an English bailiff, called in Portuguese Meirinho, a clerk, ten corporals, and 250 men. Every captain of a company had his own colours, and a drummer. [5] The combined companies of each district were referred to as a brigade.

In March 1811, he advised General Bacellar in Beira to have his Ordenanza 'in the best order and prepared for service. The companies must act independently and separately, each in its own district; unless in cases where two or more companies joining can defend a point interesting to the districts to which both belong.'[7]

The French would find them selves stranded in a barren, deserted and hostile country. Their communications would be cut and their patrols and posts continually under attack. 'In short,' wrote a British officer on the Portuguese staff, 'every strongpost upon his line of march should be made a grave of some of his people.'[8]

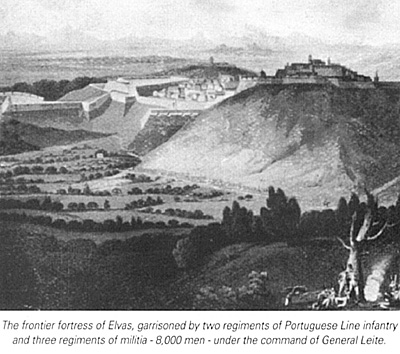

Wellington demanded the embodiment of every one of the forty-eight militia regiments of the national establishment. In theory this should have mustered some 70,000 men, but never more than 45,000 were ever under arms at any one time. Many of the districts were too sparsely populated to raise their full quota of 1,500 men, and in other districts the local authorities were unwilling or incapable of enforcing recruitment. Of these forty-eight regiments, eight were from the regions of the Alemtejo and the Algarve south of the Tagus. Three of these were taken to form the garrisons of Elvas and Campo Mayor, and the others were employed as a corps of observation on the lower Guadiana. The five regiments from the Lisbon area were engaged in building and then occupying the Lines of Torres Vedras. Three other regiments were in garrison at Almeida, two at Abrantes and one at Peniche, the remaining regiments from the Beira and the North were formed into five independent divisions under the overall command of General Bacellar. The first of these divisions - seven regiments from the coastal districts between the Douro and the Mondego under Colonel Trant - were to cover Oporto. They were additionally to prey upon the rear of the invaders as they marched upon Lisbon. Six regiments under Silveira were to guard the northern frontier region of the Tras-os-Montes against French raids from Leon. Eight regiments under Millar were to remain around Oporto as a reserve to support either Silveira or Trant. Lecor with three regiments was kept around Castello Branco, and finally, four regiments under General Miranda were stationed at Thomar from where they could either support Lecor or strengthen the garrison of Abrantes.

The real fighting, however, would be done by the Anglo-Portuguese field army. The Portuguese Army, which had been disbanded by the occupying French forces in 1807, had to be almost completely re-built at a huge cost to both the British and Portuguese Governments. From just 29,000 men in November 1808, by September 1809 there were 44,000 officers and men with the colours or in the training depots. In the Spring of 1810 Wellington was able to inform the Earl of Liverpool that the Portuguese were ready to take the field. 'We have done everything for the regulars that discipline could do....and the regulars have been armed and equipped as far as the country would go. If the Portuguese do their duty, I shall have enough.'[9]

Wellington had originally estimated that he could hold Portugal with 20,000 British troops in addition to the Portuguese forces. In November 1809 he revised that figure. 'The extent of the army which it would be necessary that His Majesty should employ on Portugal ought to be 30,000 effective men, in aid of the whole military establishment of Portugal, consisting of 3,000 artillery, 3,000 cavalry, 36,000 regular infantry and 3,000 cacadores and the militia.'

[10]

The British Government had promised to support Wellington and he was granted the extra troops that he required, the reinforcements were shipped out to Portugal throughout the winter, and by April, Liverpool was able to write the following letter to Wellington. 'Your latest returns, added to your latest reinforcements, show a total of thirty-five thousand rank and file in Portugal. Making allowance for sick and casualties, let us call it thirty thousand effective, which is the number that we agreed to give you ,' [11] Liverpool also offered to send a further 2,500 drafts and recruits, bringing the total in Portugal up to almost 40,000 men.

With these troops Wellington was able to form the Light Division in February 1810, and the 5th Division in August 1810, in addition to the four existing divisions. The 6th and 7th Divisions were created in 1811 as the campaign for the defence of Portugal unfolded. On 12 January 1810 Wellington moved his headquarters to Viseu and placed his troops accordingly: The remainder of the Cavalry (3,000 men) in ine Mondego valley. These forces were, therefore, directly facing the expected invasion front with the militia and Ordenanza on the wings. Because of the good lateral communications established by Wellington, the troops could be speedily concentrated on either side of the Tagus. The Portuguese at Thomar and the British divisions at Viseu, Guarda, Pinhel and Celorico could be brought together at Guarda or any position between Guarda and the Douro in just two marches. They would thus form a body of some 38,000 men. Likewise, the 2nd Division and the Portuguese could unite via the bridge at Abrantes, thus concentrating 32,000 men on the line of the Tagus. [12]

On 27 April Wellington advanced his headquarters to Celorico and moved the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and Light Divisions nearer to the frontier. The following month he brought up five Portuguese brigades, incorporating some of them into the British divisions. Hill's 2nd Division, along with Hamilton's Portuguese Division, remained around Abrantes. When formed, in August, the 7,000 men of the 5th Division were placed at Thomar to act as a general reserve, and in particular, to support Hill and Hamilton south of the Tagus.

These dispositions were designed to make the French move in masses. Whichever route the invaders took they would find themselves opposed by a body of 20,000-30,000 men, even if the French made simultaneous attacks on either side of the Tagus. The preparations and the movements of such large forces by the enemy would be easily detected, allowing the defenders to concentrate as many men as possible at the threatened points. To allow the rapid communication of such information, telegraphs were established from Almeida, Abrantes and Elvas, all the way back to Lisbon.

One of Wellington's biggest problems was with finance. 'Many debts still remain due on behalf of Sir John Moore's army,' he explained to Lord Liverpool. 'The people of Portugal and Spain are tired out by requisitions not paid for...and nothing can now be procured without ready payment.' [13] Originally the government had decided to take 20,000 Portuguese troops into British pay, to ease the financial burden that had been placed upon the Portuguese, at an estimated cost of £50,000 per month.

It soon became apparent, however, that this sum was inadequate and Wellington was forced to press the Cabinet for more money. Huskisson at the Treasury argued that it was impossible for him th provide anything other than paper money. 'How can you expect us to buy specie here with the exchange thirty per cent against us,' he complained to Wellington in July 1809, 'and guineas selling at twenty-four shillings?' [14]

Wellington had seen that coin was readily available for bills in Lisbon, however, and he was not dissuaded by this argument. 'It will be better,' he replied to Huskisson, 'for the Government in every view of the subject to relinquish their operations in Portugal and Spain, if the country cannot afford to carry them on.' [15] The Portuguese Regency Council did a great deal to raise extra revenue to pay for the war effort by creating new taxes, selling off some of the Royal lands and through increased borrowing.

In November 1809 the Portuguese announced a budget deficit of £900,000 and the situation became so grave that Wellington was forced to write to Liverpool. 'It will be impossible to keep the Portuguese army together, if the Government is not assisted with money to pay it regularly.'

Wellington proposed that Britain should contribute £300,000 towards the Portuguese debt and increase the monthly subsidy. A compromise was eventually reached by which the Government raised the Portuguese subsidy to £980,000 per annum and agreed to take a further 10,000 Portuguese troops into British pay. They refused, however, to be responsible for any part of the existing deficit.

Inevitably, costs continued to rise and Wellington calculated that the total expenses for one month at £272,565 for the British army, plus £80,000 for the Portuguese troops. [16] The Government, however, responded by providing a colossal £300,000 per month. In addition, Wellington was assured that there was 'no reason at present to suppose that His Majesty's Government may not be able to bear this amount.' [17]

Thus Wellington was able to afford to implement his plans for the defence of Portugal. When the French finally invaded Napoleon learned of the scope and scale of Wellington's defensive arrangements. He is reported to have said that, 'his total desolation of the Kingdom of Portugal is the result of systematic measures splendidly concerted. I could not do that myself, for all my power.' [18]

[1] Despatches, vol. 5, p 279.

More Portugal

French Invasion of Portugal Part 1: Wellington's Plans for the Defence of Portugal

'I consider the Portuguese Government and army as the principals in the contests for their own independence,' wrote Wellington to Lord Liverpool on 14 November 1809, 'and that the success or failure must depend principally upon their own exertions, and the bravery of their army.'

[1]

'I consider the Portuguese Government and army as the principals in the contests for their own independence,' wrote Wellington to Lord Liverpool on 14 November 1809, 'and that the success or failure must depend principally upon their own exertions, and the bravery of their army.'

[1]

The militia and the Ordenanza were to play important roles in the defence of the country, they were to 'do the enemy all the mischief in their power,' Wellington instructed General Leith at Elvas, 'not by assembling in large bodies, but by impeding his communications, by firing upon him fromm the mountains and strong passes, with which the whole country abounds, and by annoying his foraging and other parties that he may send out.' [6]

The militia and the Ordenanza were to play important roles in the defence of the country, they were to 'do the enemy all the mischief in their power,' Wellington instructed General Leith at Elvas, 'not by assembling in large bodies, but by impeding his communications, by firing upon him fromm the mountains and strong passes, with which the whole country abounds, and by annoying his foraging and other parties that he may send out.' [6]

1st Division (6,000 men) at Viseu

2nd Division & 13th Light Dragoons (5,000 men) at Abrantes

3rd Division (3,000 men) at Celorico

4th Division (2,400 men) at PinhelTHE FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENTS

8th (Evora) Infantry regt, 1810

8th (Evora) Infantry regt, 1810

Notes

[2] Despatches, vol. 5, p 480.

[3] A. Halliday, Observations on the Present State of the Portuguese Army, 1811, pp. 53-4.

[4] Despatches, vol. 5, p. 556.

[5] Halliday, pp. 53-4

[6] Despatches, vol. 5, pp 529-30.

[7] ibid., p. 535

[8] D'Urban, p. 76

[9] Despatches, vol. 5, p. 480.

[10] Despatches, vol. 5, p. 274.

[11] Liverpool to Wellington, 24 April 1810, quoted in J. Fortescue, History of the British Army, 1906-20, vol. 7, pp. 439-440.

[12] See W. Napier, History of the war in the Peninsula, 1886, vol. 2, pp. 394-5

[13] Despatches, vol. 5, pp. 536-8.

[14] Fortescue, vol. 7, p. 435.

[15] Wellington to Huskinsson, 28 March and 22 June 1809, quoted in Fortescue, vol. 7, p 436.

[16] This particular figure was for the period 25 May to 24 June 1810. Despatches, vol. 6, p. 174

[17] Supplementary Despatches, vol. 6, pp. 476-80: Marquess Wellesley to Villiers, and Liverpool to Wellington, 14 March 1810, vol. 5, p. 572

[18] Napoleon to Foy, quoted in Oman, vol. 3, p. 457.

Part 2: Wellington's Plans for the Defense of Portugal

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 1

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 2

Introduction

The Military Geography of Portugal

The Situation in 1810 and Fortresses

The Devastation of the Countryside and Footnotes

Back to Age of Napoleon 19 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com