The Serra da Estrella, the mountain range which divides the Beira frontier.

Portugal's border with Spain runs for some 900 miles but there

were few really practical invasion routes in 1810 for a large army

and its vast train. Portugal's main centres of population, wealth,

commerce and education were all (and still are) to be found along its

coastal strip. The land round the frontier was sparsely populated.

Large areas were mountainous, inhospitable and uncultivated.

Wellington therefore, from both a military and a moral

perspective, saw little point in trying to defend such an area. '(T)he

line of frontier of Portugal is so long in proportion to the extent and

means of the country, and the Tagus and the mountains separate

each other, and it is open in many parts, that it would be

impossible for an army, acting upon the defensive, to carry on its

operations upon the frontier without being cut off from the capital.'

Wellington, consequently, had no intention of trying to stop the

invader on the border. 'The scene of the operations of the army

would, therefore most probably be considerably within the

frontier, whether their attack be made in winter or summer. [5]

The object of the defending forces, Wellington told his

Chief Engineer, 'should be to oblige the enemy as much as possible

to make his attack with concentrated corps. They should stand in

every position which the country could afford such a length of time

as would enable the people of the country to evacuate towns and

villages, carrying with them or destroying all articles of provisions

and carriages. [6]

Wellington then intended to 'bring matters to extremities,

and to contend for the possession and independence of Portugal in

one of the strong positions in this part of the country. [7]

He could not risk engaging a superior French force with the

small army under his command, however, unless he was able to

fortify his defensive positions in advance. It was upon these

fortifications that the whole of Wellington's defensive policy was

founded.

For Wellington's plan to work it was obviously essential

for him to calculate accurately the precise route that the invaders

would take. The Portuguese frontier with Spain is naturally divided

into three definable sections. The northernmost, that from the

mouth of the River Minho to the River Douro, was not within the

scope of French operations in 1810.

It can only be reached from Galicia and the French had not

at that time subdued this province nor had they any intention of

dealing with it until after the conquest of Portugal. The occupation

of this northern area of Portugal, or even its regional capital,

Oporto, would not have brought about any significant result.

Lisbon, unlike its counterpart, Madrid was not only the political

but also the moral and economic heart of the country and whilst it

remained free, Portugal remained unconquered. To reach Lisbon

from the north two major rivers have to be crossed, the Douro and

the Mondego. It would have been virtually impossible for the

invading army to force the passage of either of these obstacles in

the face of a hostile enemy. The other two sections of the Portuguese frontier, from the

Douro to the Tagus, and from the Tagus to the Guadiana, were

both accessible to the French in 1810. This was because they were

in possession of the plains of Leon and La Mancha, and of northern

Andalucia. However, only the roads that ran north of the Tagus

travelled directly to the gates of Lisbon. Any advance south of that

river would only lead the invader to the height of Almada, where he

would still be separated from the capital by the estuary of the

Tagus.

As the Royal Navy maintained a strong presence in the Lisbon

basin, a French army camped at Almada would still be as far from

success as when it had started out from Spain. For a further thirty

miles upstream from Lisbon, the Tagus remained an impassable

barrier for an army of the nineteenth century.

From the capital northwards almost as far as Alhandra, the

Tagus forms a broad lagoon, in parts eleven miles wide. Beyond

Alhandra. the river contracts to a normal breadth, but for another

ten miles upstream the eastern bank of the river is bordered with

saltmarshes and broken by rivulets. It is only near Salvaterra de

Magos that the river could be bridged.

An invader from Spanish Extramadura. could cross it here or at

any point upstream, but the nearest permanent bridge at that time

was another sixty miles north at Abrantes. It was therefore

extremely unlikely that the principal French effort would be

delivered south of the Tagus. If used in conjunction with an attack

from the north, however, an approach from the south might prove

highly dangerous. 'The enemy will probably attack on two distinct

lines, the one south, the other north of the Tagus,' Wellington told

Colonel Fletcher, 'and the system of defence must be founded upon

this general basis ... His object will be, by means of the corps

north of that river, to cut off from Lisbon the corps opposed to

him, and to destroy it by an attack in front and rear'. [8]

This was Wellington's greatest fear. A threat from the Northern

frontier could draw the Anglo-Portuguese army away from the

Lisbon peninsula. This could allow a subsidiary force from the

south to bridge the Tagus and cut Wellington's army off from the

capital. Wellington decided that if the French had a field army

anywhere in the vicinity of Badajoz or Elvas, then he would have

to leave a considerable portion of his own force south of the Tagus.

The principal French effort, nevertheless, would almost

inevitably be delivered north of the Tagus somewhere along the

ninety or so miles of the Beira frontier. This district, between the

Douro and the Tagus, was land that Wellington had only a limited

knowledge of, but he had ordered the entire area to be carefully

mapped. By the winter of 1810 most of Central Portugal had been

accurately mapped on a scale of four miles to the inch.

The information was gathered from a variety of sources,

but mainly from the reconnaissance made by specifically employed

'exploring officers'. The Beira frontier is divided into two by the

Serra de Estrella which crosses the border line at right angles,

halfway between the Douro and the Tagus. The passes either side

of the Estrella were described by Wellington as 'two great entrances

into Portugal'. An invader must make his advance either to the

south or to the north of the Serra. To attempt to march his army on

both sides of the range would leave the two columns completely

separated.

South of the Estrella, through Coria, were two routes. One

ran through the mountains of the Sobriera. Formosa, the other via

Castello Branco, Abrantes and the valley of the Tagus. It was along

the first of these routes that Junot invaded Portugal in the winter of

1807-8. This road was the worst that could be found between the

Serra da Estrella and the Tagus. Even though Junot's march had

been unopposed he lost many men on the way and eventually he

had to leave behind his artillery.

Along this route there were long stretches where water was

difficult to find. Parts of the main road were so steep that to move

a sixpounder (by no means the heaviest of field ordnance) required

not only a dozen horses but also the assistance of fifty men.

Junot's experience served as a warning to the other French generals

and this road was never used again for an advance against the

Portuguese capital. The second route was a likely avenue for the

invaders to take. It would probably have involved the French

having to force the passage of the Zezere river in the face of the

defending army. It would certainly have entailed besieging the

fortress of Abrantes.

There were actually two roads that ran east of the Zezere,

the old Castello Branco road and the new by-road, the Estrada

Nova. If the French were to invade in this direction it would be

along the Estrada Nova that they would march. This was in spite

of the fact that it ran along an absolutely uninhabited mountain-side

where for long sections along its length water was completely

unobtainable. Even though Wellington doubted that the French

would use this road he decided to completely eliminate it from all

consideration by destroying it. He ordered the road to be blasted

with gunpowder along several points where the track passed along

deep precipices. At these points the whole roadway was blown or

shovelled down into the gulf below rendering it absolutely

impassable for guns and wagons. [9]

Companies of irregular troops were stationed at each point

to hinder any attempts by the French to repair the road.

North of the Estrella, through Ciudad Rodrigo and

Almeida, were three routes: one by the valley of the Douro and two

by the valley of the Mondego. The route by the Douro ran through

Pinhel and Lamego and led only to Oporto and Northern Portugal,

and could be of no practical use to an invading army aiming for

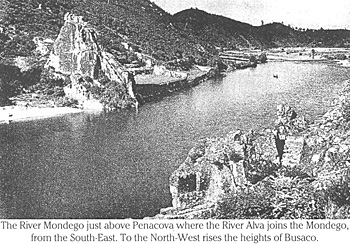

Lisbon. This left just two roads for the French to take, both of

which ran into Coimbra, one north of the Mondego, the other to the

south of that river.

So although Wellington had some 400 miles of frontier to

defend, there was no doubt in his mind that the main French

advance would be made along either of these two roads. Although

these roads crossed some difficult ground, they also ran through

areas of cultivated land and a number of villages. Of the two, the

route south of the Mondego, through Celorico and Ponte de

Murcella, was far superior to the Celorico-Viseu-Coimbra road, and

was also considerably shorter. Both of these two roads offered

Wellington a choice of good defensive positions. The northerly

route crossed the high granite

ridge of the Serra de Busaco, which was one of the most formidable

positions in the whole of Northern Portugal. The southern route,

the one that Wellington firmly believed the French would follow,

contracted into a difficult defile at the Ponte de Murcella over the

River Alva. The Busaco heights required no strengthening. At

Ponte de Murcella, however, Wellington ordered the construction

of a line of earthwork redoubts. It was here that he calculated that

he would 'fight a battle to save the country.' [10]

Wellington was not simply going to chance everything on a

single pitched battle however, despite the strength of the defences

he was building at Ponte de Murcella. 'I have fought battles

enough,' he told Sir Charles Stuart, 'to know that even under the

best arrangements, the result of any one is not certain'. [11]

The position on the Alva could also be turned from the

south by an invading army crossing the Tagus. So although

Wellington hoped to be able to stop the French at Ponte de

Murcella, he had to find further defensive positions below the

point where the Tagus could be crossed. He knew that the most

important consideration was the defence of Lisbon. 'In case the

enemy should make a serious attack upon Portugal, 'Wellington

wrote to Admiral Berkeley, who commanded the British squadron

in the Tagus, 'his object, as well as that of the allies, would be the

possession of the city of Lisbon'.

Wellington was prepared to give up the rest of the country

to the invaders in order to 'confine ourselves to the preservation of

that which is most important - the capital. [12]

Although Wellington hoped to be able to hold the French at

Ponte de Murcella, his final stand would, in all probability, be in

front of Lisbon. At Torres Vedras, less than thirty miles north of

the capital, would be built the great line of fortifications that would

defy the mighty legions of the Emperor Napoleon.

The Lines of Torres Vedras, though they were the most

important and elaborate feature of Wellington's strategic plans,

were only part of a completely integrated defensive policy. This

included the re-organisation of the Portuguese Regular Army and

the mustering of the militia, together with the revival of the ancient

call to arms of the Ordenanza. It also required the destruction or

removal of every commodity that would be useful to the enemy.

The organisation and implementation of these schemes, however,

would require time, and the more time that Wellington had the more

complete would be his arrangements. Fortunately, the military

situation in Spain encouraged Wellington to believe that he would

be granted the time he so desperately needed.

French Invasion of Portugal Part 1: Wellington's Plans for the Defence of Portugal

More Portugal

Moore's assessment of Portugal was not entirely invalid and

Wellington agreed with him that 'the whole country is frontier, and

it would be difficult to prevent the enemy from penetrating by

some point or other. [4]

Moore's assessment of Portugal was not entirely invalid and

Wellington agreed with him that 'the whole country is frontier, and

it would be difficult to prevent the enemy from penetrating by

some point or other. [4]

The River Mondego just above Penacova where the River Alva joins the

Mondego, from the South-East. To the North-West rises the heights of Busaco.

The River Mondego just above Penacova where the River Alva joins the

Mondego, from the South-East. To the North-West rises the heights of Busaco.

Introduction

The Military Geography of Portugal

The Situation in 1810 and Fortresses

The Devastation of the Countryside and Footnotes

Part 2: Wellington's Plans for the Defense of Portugal

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 1

Massena's Invasion of 1810 Part 2

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 17 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com