Dutch During The Revolutionary Wars

Dutch During The Revolutionary Wars

French Invasion of

Dutch Republic: 1793

Introduction

By Geert van Uythoven, The Netherlands

| |

Part V

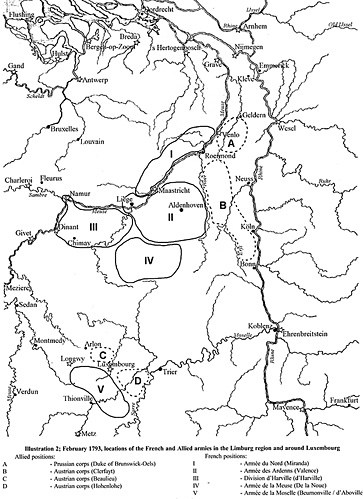

As already described in my previous article, on 1 February 1793 France declared war on the King of Great Britain and the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. In response, on 5 February, Great Britain declared war on France. However, French military reaction was initially slow, only the fortress-cities Venlo, Roermond and Maastricht (the latter city part of the Austrian Netherlands), in what I will call for simplicity the Limburg region, were threatened.

After having declared war on the King of Great Britain and the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, the Convention Nationale ordered Dumouriez to attack the Dutch Republic immediately. During December 1792, Dumouriez was ready to attack the unprepared Dutch, but at that time the Jacobins did not want to have additional foreign involvement while they were still struggling for power in France. But now Dumouriez initially hesitated. There were only about 18,000 men [2] with about 40 guns available for the advance into the Dutch Republic (although in their proclamations the French boasted 100,000 men!), forming the Armée de Hollande. The convention on 24 February ordered a levée of 300,000 men, but of course it would take months before this measure would be effective and the first of them would be ready to take the field.

By advancing into the Dutch Republic Dumouriez would dangerously expose his right flank, with strong Prussian and Austrian forces present. Further, he was desperately short of weapons, horses, clothes and money. But being put under pressure by the National Convention, he gambled everything on one card, opting for a quick advance and an easy victory. This would provide him with everything he lacked, delivered by the renowned ‘richest state of Europe’, and would give him a chance to consolidate his positions and to turn his attention to the Prussians and Austrians, besides giving him enough prestige to reach his goals in Paris. Dumouriez left Paris on 26 January and arrived in Antwerp a few days later. He immediately started making plans for the upcoming campaign, assisted by his able chief of staff General Pierre baron Thouvenot. Having decided to attack, Dumouriez had three options open:

The first option was an advance through the western part of the Dutch Republic, by way of the province Zeeland. This was the option the Dutch patriot exiles advised. However, an advance through Zeeland would be very difficult and slow. The French would have to cross the estuaries of the Rivers Scheldt, Rhine and Meuse, with the need to conduct complicated amphibious operations, across a number of wide waterways defended by the combined Dutch and British navies. Not a viable option taking in account the speed with which the advance would have to take place.

The second option was an advance through the eastern part of the Dutch Republic, by way of Nijmegen and Arnhem, initially preferred by Dumouriez himself. This was the advance line Louis XIV had chosen in 1672 and 1702. Although an advance here would have its flanks covered by the rivers Rhine on the right and Meuse on the left, the French would be dangerously near the Prussian and Austrian forces, and easy cut off. Furthermore, an advance through this part would not directly threaten the heart of the Dutch Republic, the province Holland.

So the only reasonable option left was an advance in the centre, through the province Brabant. An advance here would meet no serious problems or obstacles, except for the necessary crossing of the rivers Rhine / Waal and Meuse.

Having chosen to advance in the centre, Dumouriez planned to move with his Armée de Hollande along an advance line that would leave the fortress-cities Breda and Geertruidenberg on his right and the fortress-cities Bergen-op-Zoom, Steenbergen and Willemstad on his left. These cities would be covered by sufficient forces to prevent any sorties, while Dumouriez would try to cross the swampy estuary called Biesbosch, near Dordrecht. In this way he hoped to avoid a crossing of the probably heavily defended rivers, and would arrive directly in the heart of the Dutch Republic. Hearing later that the river banks of the Hollandsch Diep, near the village Moerdijk, were still undefended, with only a few boats present to prevent a French crossing, Dumouriez decided to cross here. He would continue his advance by taking the cities Rotterdam, Delft, The Hague, Leiden, Haarlem and finally Amsterdam, not expecting much resistance because of his bold advance from an unexpected direction.

Further, Dumouriez’ whole plan was based on the assumption that the Dutch army would present no real threat, and that the Dutch inhabitants, according to his view mainly patriots, would give extensive help to his troops in any way they could. This view was strengthened by the patriot exiles fighting in the French ranks, especially by Colonel Herman Willem Daendels. [3] Dumouriez expected to augment his army with 25,000 to 30,000 Batavian volunteers.

As may be remembered from the previous article, on the Scheldt in front of Antwerp a French squadron was present. The squadron consisted of the frigate l’Ariel (24 or 28 guns, sources differ), the gun-brig la St. Lucie (14 guns), and three gunboats armed with 24-pdr guns. This small squadron was commanded by the by now promoted Captain Moultson, an American officer in French service. He had orders to demonstrate on the Scheldt, in front of the Dutch held fortress Bath, in order to keep busy as many Dutch troops and ships as possible.

Dumouriez made also preparations for a defence line if he had to retreat again. He prevented the defences of Mons and Tournay being dismantled as was ordered by the former minister of war Pache. In addition, the heights at the castle of Huy were fortified, Mechelen surrounded with an earth wall, and batteries erected near Ostend, Nieuport and Dunkirk. Further, Dumouriez wanted to connect the border fortresses with fortified positions. A defence line would have to be prepared between Dunkirk and Burgues; at Mont Cassel a fortified camp would be erected; Orchies, Bavay and Beaumont would be fortified. The defence line contained further the fortress-cities Lille, Douay, Condé, Quesnoy, Maubeuge, and Philippeville. The chief of staff of Dumouriez, General Thouvenot, assisted by the commissaire Petit-Jean, were ordered to raise and bring up to strength as soon as possible 25 to 30 “Belgian” battalions, each 800 men strong.

In the Limburg region all attention was focused on three cities: Venlo, Roermond and Maastricht, all three located at the River Meuse. Venlo and Maastricht were on Dutch territory, Roermond was part of Austrian Geldern. Venlo was a Dutch enclave in the middle of Prussian Geldern, east of the Meuse. Its garrison, commanded by Lieutenant-General Frederik Unico Baron van Mönster, consisted of only 200 men with two guns, the remaining guns and garrison having been evacuated during the previous weeks! In addition, there were no provisions, and the citizens were mostly pro-French. On the west bank of the Meuse, opposite Venlo, the fortress St. Michel was situated. Although the fortress was totally closed, it lacked palisades and casemates. Its souterrains were flooded. Communication with Venlo proper was difficult, because there was only a flying bridge. It had no garrison, because with only 200 men present in Venlo understandably none could be spared to garrison this fortress as well.

On 6 February the main body of the Armée du Nord, 13,000 French troops commanded by Lieutenant-General Miranda, cut off Maastricht. As well as commanding the Armée du Nord Miranda was at the same time interim commander of the Armée des Ardennes instead of Jean-Baptiste-Cyrus-Marie-Adélaide de Timbrune de Theimbronne, compte de Valence, who was interim commandant en chef during the absence of Dumouriez. The Armée du Nord consisted of the troops depicted in Table A. [4] The blockade and subsequent bombardment of Maastricht was led by a very experienced engineer, Lieutenant-General Benoît-Louis Bouchet, who had already been present during an earlier siege of Maastricht by the French, in 1747. The siege of Maastricht will be treated in the next article. The main force of about 45,000 men took up positions between Düren and Aldenhoven, opposite the Austrian main army behind the rivers Ruhr and Erft.

French forces advanced into the Prussian territory west of the River Meuse. On the 11th the fortress Stevensweert, on the west bank of the River Meuse southwest of Roermond, was captured. Its garrison consisted of a sergeant, a corporal and twelve soldiers, who were surprised in their sleep at 06.00am by the 1er bat/d’Ille-et-Vilaine, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Jean-Victor Moreau. [5] The French further had outposts at Blerick (near Venlo) and Kessel. In Prussian Geldern stood a Prussian army to cover Prussia’s Westphalian provinces, commanded by Friedrich August D. Herzog von Braunschweig-Oels (Duke of Brunswick-Oels). The Duke of Brunswick-Oels’ field army consisted of the troops depicted in Table B, [6] about 11,400 men strong. When the Duke of Brunswick-Oels arrived in Wesel on 23 January to take over command of the army, he was confronted with the lack of many basic requirements, especially light troops and field artillery.

To remedy the latter, he took from the guns in Wesel four 6-pdr and six 4-pdr guns, and two howitzers, using them two create two field batteries of six guns each. The lack of light troops was especially felt because of the countless marauding expeditions by French soldiers on Prussian territory at both sides of the Meuse. To remedy this, the Duke of Brunswick-Oels borrowed 200 Austrian uhlans from FZM Clerfayt. Further, he took 80 Schützen 6 from each of the Regiment No. 44 von Kunizky and the Regiment No. 48 von Köthen. Thirdly, he took 100 handpicked men from the Westphalian depot-battalions of the Regiment No. 10 von Romberg and the Regiment No. 48 von Köthen. The main field army initially assembled round Wesel. During the first days of February, the army crossed the Rhine and took up positions east of Venlo, with outposts along the River Meuse. Gradually these outposts had to be reinforced, because the French started to cross the river with small boats, carrying men enough to plunder the farms and cottages lying on the east bank of the river. To prevent actions of this kind, the Prussians demolished all the boats and ferries they could lay their hands on.

Only on 9 February, from a French newspaper dated 2 February, did the Prussians learn that on the 1st of that month France had declared war to the Dutch Republic and Great Britain. This fact had direct results for the Prussians, because the Prussian right flank, covered up to this date by neutral territory, was now wide open. Strategically seen a French advance in this direction was not very likely, but for the Duke of Brunswick-Oels, apparently the threat was very real! Venlo, the ideal crossing point for the French was the biggest threat. Even more now that the advance guard of the Armée du Nord, consisting of about 3,000 men and commanded by Colonel Albert-Victoire Despret, known as La Marlière, already had occupied Roermond -without any resistance. Venlo was now threatened from both banks of the River Meuse. Therefore, the Duke of Brunswick-Oels decided to prevent a French occupation of Venlo by occupying it first. For this purpose, on 10 February the Prussian field army advanced on Venlo. The greater part took up positions at the road to Roermond, to prevent the French from interfering, while the Duke himself marched to Venlo with the remaining troops.

On the 11th, at daybreak, the Duke arrived before the gates and persuaded the officer of the guard to let him enter with his suite. The Duke however had no intentions of holding exhaustive negotiations, and his suite was immediately followed by the Regiment No. 27 von Knobelsdorf, both musketeer battalions of the Regiment No. 44 von Kunitzky and cavalry. The Prussians troops marched to the market place, while the Duke of Brunswick-Oels went to the governor, Lieutenant-General van Mönster. Van Mönster was surprised by what formally was a breach of the neutrality of Dutch territory, but taking in account the political situation Van Mönster soon accepted the Prussian presence. On the 15th, as a representative of the General States of the Dutch Republic, Van Mönster proposed to the Duke of Brunswick-Oels that the Prussian garrison of Venlo would be under orders of the General States of the Dutch Republic. This proposal was rejected.

The occupation of Venlo gave effective cover to the Prussian right flank. Therefore, the Prussian troops were shifted to the south, closer to the Austrians. The Division von Kospoth, save the 2nd Musketier-Bat / Regiment No. 48 von Kothen, formed the right flank of the Prussian army and had to cover the Austrian right flank. The Duke of Brunswick-Oels moved his headquarters from Geldern to Kempen. Major General von Pirch was appointed governor of Venlo, and the Prussian troops brought the fortress-city as much as possible into a proper state of defence. A decision had to be made about what to do with the fortress St. Michel, on the other side of the Meuse. The state of this fortress has already been described, and the Duke of Brunswick-Oels did not want to sacrifice his men to defend such a bad position. Because it was a Dutch fortress, the Duke proposed to Lieutenant-General van Mönster that he should defend it with his 200 Dutch soldiers. But Van Mönster refused, knowing the bad state the fortress was in also, and officially stating that he still was responsible as governor for the city itself.

On the 12th, the fortress St. Michel was occupied by maréchal de camp Félix-Marie-Pierre Chesnon de Champmorin, who commanded 5,000 men of the Armée du Nord. The French cut nine embrasures in the parapet facing Venlo. The Prussians answered with artillery fire, but could not do much to prevent the French efforts. Initially, the French deployed one gun only, but soon more would follow. The Duke of Brunswick-Oels moved his headquarters from Geldern to Kempen. Major General von Pirch was appointed governor of Venlo, and the Prussian troops brought the fortress-city as much as possible into a proper state of defence. A decision had to be made about what to do with the fortress St. Michel, on the other side of the Meuse. The state of this fortress has already been described, and the Duke of Brunswick-Oels did not want to sacrifice his men to defend such a bad position. Because it was a Dutch fortress, the Duke proposed to Lieutenant-General van Mönster that he should defend it with his 200 Dutch soldiers.

Everything was done to strengthen the defences of Venlo. Thanks to the efforts of Major General von Pirch and the Dutch commissioner Houchart, sufficient cannon and mortars soon arrived. Initially, from the fortress Grave two mortars, four howitzers and ten Coehoorn-mortars [7] were fetched, transported on wagons. On the 20th a ship arrived from the same fortress, carrying a huge amount of cannon, mortars and ammunition. The fortress was now armed with 66 pieces, consisting of the following:

Dutch:

The Austrians had promised an additional three mortars, which arrived on the 23rd. The lack of artillerymen was solved by using the reserve-artillerymen of the infantry-regiments, and by using soldiers who had previously served with the artillery in foreign armies! [8] In addition, on the request by the Duke of Brunswick-Oels, the governor of Nijmegen sent two artillery officers, two NCO’s and ten bombardiers.

Also on the 20th the General Adjutant of the Dutch hereditary Stadtholder, Count Bentinck, arrived at the headquarters of the Duke of Brunswick-Oels, informing him that a Dutch corps, commanded by Prince Frederick of Orange, would cross the Meuse and take up positions south of the city Grave. This corps consisted of the following troops:

On the 25th, Prince Frederick of Orange himself arrived with the Duke of Brunswick-Oels, declaring his eagerness to operate against the French in close co-operation with the Prussians. As a result, plans were made for a joint operation, which were as follows: On 1 March, Prince Frederick would advance south with his troops, driving before him the weak French forces present. On the 2nd he should arrive in front of the villages Brockhausen and Lottum on the west bank of the Meuse, which were known to be occupied by the French. The Prussians, when noticing the arrival of the Dutch troops, would bombard both villages from the other side of the river. On the same day, the Prussians would start bombarding the fortress St. Michel, on the west bank opposite Venlo. If the French had not evacuated Brockhausen on the 3rd, Prince Frederick would dislodge them, take the village and continue his march to the fortress St. Michel to capture this position also.

After having reached this goal, the Dutch as well as the Prussians would stay in place and wait for the advance of the main Dutch field army, commanded by Prince William of Orange, concentrating near ‘s Hertogenbosch, to adjust all operations with each other. If it should happen that the French would be much surprised by the advance of Prince Frederick, there could be a chance that the Dutch could continue their advance to threaten Roermond, after which the Duke of Brunswick-Oels would attack this fortress on the 5th from the other side of the river. An interesting plan, but nothing would come of it. On his return at his headquarters, Prince Frederick learned of the capitulation of Breda on 24 February, receiving orders from Prince William of Orange to march to ‘s Hertogenbosch immediately to cover this city.

More Part VI: French Invasion of Dutch Republic: 1793 The Dutch During the Revolutionary Wars

Battle of Swalmen, 1793 Part 12 [FE65] Defense of the Dutch Republic 1793 Part 11 [FE64] Siege of Willemstad 1793 Part 10 [FE63] Klundert and Willemstad 1793 Part 9 [FE62] Breda and Geertruidenberg 1793 Part 8 [FE60] Battle of Maastricht 1793 Part 7 [FE59] Austrian Troops and Dutch Defense Part 6 [FE57] Intermezzo 1787 - 1793 Part 5 [FE56] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part IV Part 4 [FE47] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part III Part 3 [FE46] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part II Part 2 [FE45] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part I Part 1 [FE44] Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #57 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2001 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

One of the causes of the delay was the absence of the commandant en chef in the northern theatre, General Charles-François du Perrier, better known as Dumouriez or Dumourier (at right). Dumouriez had gone to Paris, arriving there on 1 January 1793, to protest against the bad treatment of the Belgian people,

[1] but even more to lobby for his own political career. During the second half of February, the French advanced into the southern part of the Dutch Republic, the Brabant province. In the Limburg region hostilities commenced as already told earlier. Before detailing the advance into the Dutch Republic, I will describe what happened in the Limburg region, during the first period of the campaign a more or less secondary theatre, after having described the preparations for the French offensive.

One of the causes of the delay was the absence of the commandant en chef in the northern theatre, General Charles-François du Perrier, better known as Dumouriez or Dumourier (at right). Dumouriez had gone to Paris, arriving there on 1 January 1793, to protest against the bad treatment of the Belgian people,

[1] but even more to lobby for his own political career. During the second half of February, the French advanced into the southern part of the Dutch Republic, the Brabant province. In the Limburg region hostilities commenced as already told earlier. Before detailing the advance into the Dutch Republic, I will describe what happened in the Limburg region, during the first period of the campaign a more or less secondary theatre, after having described the preparations for the French offensive.

It was still a desperate gamble, but Dumouriez had little choice. During his advance, Lieutenant-General Francisco de Miranda, commanding the Armée du Nord, would undertake a diversion by besieging and bombarding the fortress-city Maastricht with part of his troops, while the remainder would advance to Nijmegen. After Dumouriez had passed the Biesbosch, Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste-Cyrus-Marie-Adélaide de Timbrune de Theimbronne, compte de Valence (at right), commanding the Armée des Ardennes, would relieve Miranda before Maastricht, who then would execute his task by marching with 25,000 men to Nijmegen, by way of Cleve, and at the same time prevent the Prussians coming to the aid of the Dutch. Finally Miranda would advance to Utrecht to link up with Dumouriez’ army. Miranda also would have to try to take Venlo, to prevent the Allies crossing the River Meuse at this point. Farther south, Lieutenant General Louis-Auguste compte d’Harville, commanding about 10,000 men, would concentrate near Namur, while Lieutenant-General René-Joseph chevalier de la Noue, commanding the Armée de la Meuse, would concentrate near the River Roer.

It was still a desperate gamble, but Dumouriez had little choice. During his advance, Lieutenant-General Francisco de Miranda, commanding the Armée du Nord, would undertake a diversion by besieging and bombarding the fortress-city Maastricht with part of his troops, while the remainder would advance to Nijmegen. After Dumouriez had passed the Biesbosch, Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste-Cyrus-Marie-Adélaide de Timbrune de Theimbronne, compte de Valence (at right), commanding the Armée des Ardennes, would relieve Miranda before Maastricht, who then would execute his task by marching with 25,000 men to Nijmegen, by way of Cleve, and at the same time prevent the Prussians coming to the aid of the Dutch. Finally Miranda would advance to Utrecht to link up with Dumouriez’ army. Miranda also would have to try to take Venlo, to prevent the Allies crossing the River Meuse at this point. Farther south, Lieutenant General Louis-Auguste compte d’Harville, commanding about 10,000 men, would concentrate near Namur, while Lieutenant-General René-Joseph chevalier de la Noue, commanding the Armée de la Meuse, would concentrate near the River Roer.