Intermezzo 1787 - 1793

Intermezzo 1787 - 1793

The Dutch During The Revolutionary Wars

Part V

Introduction

By Geert van Uythoven, The Netherlands

| |

Part IV

The Prussian invasion of Holland in 1787 put an end to the power of the patriots.

[1] For the time being William V of Orange was stadtholder again of the restless provinces forming the Dutch Republic.

So most of them stayed at home, or at the most took cover in a Dutch city. Therefore, the States-General asked the Prussian king to leave behind 3,000-4,000 Prussian soldiers in Holland until sufficient German troops could have been hired to augment the army [3], in order to guarantee reliable garrisons for the most important fortresses. The King of Prussia agreed to this, and even offered to pay the troops himself, if the States-General would take care of their provisions. The last Prussian soldiers left the Dutch Republic on 6 May 1788, after the German troops that had been hired arrived; 2,906 men from the Duke of Brunswick, 1,389 men from the Count of Anspach, and 1,000 men from the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

The behaviour of the Dutch Republic was rather dualistic. Inside the Dutch Republic, care was taken that the patriots lost all their power, and that they were removed from the important political positions. On the other hand, Belgian or Brabantian patriots, resisting Joseph II, ruler of the Austrian Empire that included Belgium, found refuge on Dutch soil. The Belgian patriots were admitted because of two reasons. First, to prevent them to take refuge in France. Secondly, out of revenge, because the Dutch patriots found refuge in Belgium! In addition, relations with Joseph II were already bad, because the Austrian emperor wanted free passage on the river Scheldt (in which he did not succeed), and the evacuation of the so called ‘barrier cities’ by the Dutch army (in which he did succeed).

[4]

The Belgian patriots formed a committee in Breda, led by Van der Noot, and they even formed their own army under Colonel van der Mersch, armed with Dutch weapons; In July 1790 for example the Mecklenburg Corps in garrison in ‘s Hertogenbosch received new muskets. The old ones were sold to the Belgian patriots for three guilders a piece.

Jumbo Map of 1793 Dutch Republic (slow: 178K)

On 24 October 1789, the Austrian emperor was declared to be extinct from his rights as Duke of Brabant and Count of Henegouwen, and invaded Belgium. The Austrian troops under General d’Alton lost the war and had to capitulate, and on 17 December Van der Noot entered Brussels and the independent Vereenigde Belgische Staten (‘United Belgian States’) were declared. However, during 1790 the Austrians, now under Austrian Emperor Leopold II, counterattacked, and Austrian Marshal Bender defeated the Belgian patriots and retook Belgium. The exiled Belgian patriots -- including men who would make name for themselves in the following years, such as Dumonceau, Ghigny and Lahure -- joined the Dutch patriots already present in France. They all now had the same cause to fight for.

In the meantime, in France the Revolution was taking place, and as a result Prussia, Saxony, and Austria allied themselves on 7 August 1791 at Pillnitz to bring back Louis XVI on the French throne. Later that year and during 1792 other countries joined the coalition, but their contribution was insignificant. With the Dutch invasion of 1787 still fresh in his mind, King Frederick William II of Prussia was confident he could pull off the same in France without any trouble. Again, the Duke of Brunswick, ‘experienced’ in these matters, would lead the attack. As we now know, things would go differently this time. The Prussians were not very active, and Austrian strength in Belgium was less then a third of the Prussian strength.

Great Britain as well as the Dutch Republic stayed neutral initially. After the events of 10 August 1792, during which King Louis XVI was taken prisoner and his Swiss guard was slaughtered, both countries recalled their ambassadors from Paris, still stating they had no desire to meddle themselves with the internal affairs of France. However, the retreat of the Prussian army, and the defeat of the Austrian army at Jemappes on 6 November 1792 made a huge impression on the French. Before this experience most of the French Revolutionary leaders did not really think it would be possible for them to defeat the regular armies of Prussia and Austria.

Lieutenant General Charles-François de Perrier, known by the name Dumouriez conquered the whole of Belgium within three weeks. The French lines were pushed forward as far as the border of the Dutch Republic and the cities Venlo and Achen, while the government of the Austrian Netherlands found refuge in the cities Roermond and Maastricht. If the French had followed up their advance into the Dutch Republic resistance would have been virtually impossible. However, the sorry state the French revolutionary armies were in prevented any further advance for the moment. How much wanted by the Dutch patriots that had taken refuge in France, the order to attack the Dutch Republic was not given, and to be real, if it was given could not have been carried out. The French soldiers lacked everything, even muskets, and supplies were non-existing. The Dutch patriots formed a ‘Comité Revolutionair’, a ‘revolutionary committee’, and called on their brethren in the Dutch Republic to raise against William V. However, the time was not yet right.

Not surprisingly, tension between France and the Dutch Republic was rising. The States-General still felt themselves safe, with the promised support of Great Britain and Prussia, and no preparations were made for the eventuality of a war. Great Britain itself did nothing, sitting on the fence, safe on the other side of the channel and seeing their archenemy France becoming weaker every day. The British even felt some sympathy for the French. The French however where much less careful in their relations with the neighbouring countries. By now, they had promised their support to all suppressed nations that would want to free themselves from their oppressors. In Belgium, Dumouriez demanded free passage across Dutch territory through the fortress-city Maastricht. Next, the French claimed free passage on the river Scheldt, closed by the Dutch to prevent all shipping to Antwerp, a right internationally recognised by the treaty of Westfalia in 1648.

On 22 November 1792, the French gun-brig la St. Lucie (14 guns) arrived at the roads of Flushing, followed a few days later by the frigate l'Ariel (24 or 28 guns, sources differ), three gunboats armed with 24-pdr guns, and three armed fishing-boats from Dunkirk. This small squadron was commanded by a Lieutenant Moultson [5], an American officer in French service, who demanded, in the name of Lieutenant-General Dumouriez, free passage on the river Scheldt, in order to support the siege of the citadel of Antwerp. The citadel of Antwerp occupied by the Austrians still held out, while the French already captured the city itself. The Dutch had only three armed vessels at hand, no match for the French.

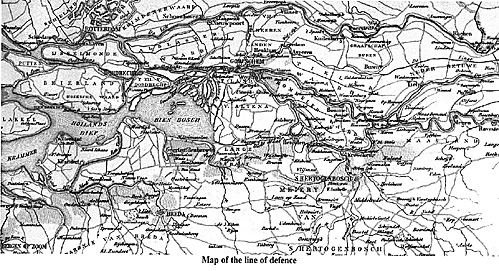

Jumbo Map of Line of Defense (extremely slow: 545K)

Therefore, they tried to reason with Mouton, and were denied permission to enter the Scheldt. Lieutenant Moultson however referred to Dumouriez’ explicit orders, and on 1 December 1792 he set sail, entered the river Scheldt and sailed to Antwerp, in plain sight of the Dutch guard-ship lying at Bath. The Dutch were not prepared to counter such a move and strongly protested to the French government. Captain Jan Schreuder Haringman was ordered to move to Zeeland, and to take over command of all warships present. In addition, all available warships were ordered to sail to Zeeland.

The British also were not amused at all. Antwerp was the ‘pistol on the breast of Great Britain’, and its capture by the French combined with free passage on the river Scheldt was a direct threat to Britain’s security. Pitt told the French ambassador in London that the British never would allow the one-sided breach of an agreed treaty. A British squadron set sail for Zeeland. The Dutch Republic was made clear that the British would fulfil their obligations deriving from the alliance of 1788. The Prussians declared the same. In spite of this, the Dutch choose the easiest way out and opened secret negotiations with Dumouriez in order to prevent, or at least slow down a French attack on the Dutch Republic. They were even prepared to recognise the French revolutionary government.

However, events in Paris prevented all this. On 21 January 1793, Louis XVI met his death on the Place de la Révolution. Europe was struck with horror. Spain, the German Empire, Russia, Portugal, Naples, both Sicily’s and Toscane all joined the Coalition against France. Real military support from these countries however would be minor or even non-existent. On 24 January, Great Britain ordered the French ambassador to leave the country within eight days. The French National Convention took this move as an affront without any grounds. As a result, and also to lay their hands on the huge amounts of money supposed to exist in the very wealthy Dutch Republic, on 1 February 1793 France declared war, not only on Great Britain but also on the Dutch Republic. In revolutionary stile, war was declared on the King of Great Britain and the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. The National Convention forgot in their haste that Willem V was not, as a stadtholder, head of state, but only the first servant of the Republic. Who cared. The pieces were set. The game was now to be played.

More Part V: Intermezzo 1787-1793

The Dutch During the Revolutionary Wars

|

To strengthen the position of William V even more, on 15 April 1788 treaties were concluded between the Dutch Republic, and respectively Great Britain and Prussia. These treaties stipulated mutual assistance in case of an attack, and that the latter countries guaranteed the hereditary rights of the House of Orange in the Dutch Republic. This was followed on 13 August 1788 by an alliance concluded between Prussia and the Dutch Republic, to support each other in case of an attack. The side-effect of all this was that in international affairs, the Dutch Republic was highly dependent on Great Britain and Prussia, and because of this and the fact that France has promised the patriots their assistance (that however failed to materialise), relations with France deteriorated.

After the Prussian invasion the disarming and disbandment of the Freecorps was difficult, and it took a few weeks before riots between Orangists and patriots ceased to occur. In addition, the reliability of the Dutch army was doubtful, with so many units having fought on the patriot side. It would take time before the depleted Dutch army was brought up to strength again. Therefore, the Dutch Republic was very vulnerable, especially with so many patriots within its borders. Although many Dutch sources state that about 40,000 patriots had left the country to seek refuge in Belgium and France, Colenbrander has convincingly reasoned that their number was not more than 5,000 or 6,000 at the most. [2]

To strengthen the position of William V even more, on 15 April 1788 treaties were concluded between the Dutch Republic, and respectively Great Britain and Prussia. These treaties stipulated mutual assistance in case of an attack, and that the latter countries guaranteed the hereditary rights of the House of Orange in the Dutch Republic. This was followed on 13 August 1788 by an alliance concluded between Prussia and the Dutch Republic, to support each other in case of an attack. The side-effect of all this was that in international affairs, the Dutch Republic was highly dependent on Great Britain and Prussia, and because of this and the fact that France has promised the patriots their assistance (that however failed to materialise), relations with France deteriorated.

After the Prussian invasion the disarming and disbandment of the Freecorps was difficult, and it took a few weeks before riots between Orangists and patriots ceased to occur. In addition, the reliability of the Dutch army was doubtful, with so many units having fought on the patriot side. It would take time before the depleted Dutch army was brought up to strength again. Therefore, the Dutch Republic was very vulnerable, especially with so many patriots within its borders. Although many Dutch sources state that about 40,000 patriots had left the country to seek refuge in Belgium and France, Colenbrander has convincingly reasoned that their number was not more than 5,000 or 6,000 at the most. [2]