Intermezzo 1787 - 1793

Intermezzo 1787 - 1793

The Dutch During The Revolutionary Wars

Part V

Dutch Preparations for War

By Geert van Uythoven, The Netherlands

| |

Part IV

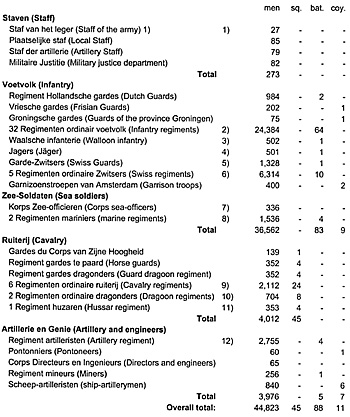

The Dutch Republic was a seafaring nation. Land armies had less interest for the Government and the people as a whole, for as long as the Republic had existed. Conscription did not exist. The Dutch army was neglected. In spite of the dangerous situation in Europe, and the bad relation with the southern neighbour Austria (present in the southern -Austrian- Netherlands) the Dutch States, the Dutch were only interested in making money and not spending it on defence. Nothing was done to strengthen the army or to maintain the fortresses in good condition. All units in the Dutch Republic were paid and were official in the service of a particular province, not by the Dutch Republic itself. These provinces then, placed the greater part of these units under the command of the States. Nominally, Commander in Chief of these units was the Captain-General, the stadtholder Prince William V of Orange-Nassau, although on important decisions he had to confer with representatives of the States-General. Because of this arrangement, a unit had to swear first an oath to the province in which service it was, and an additional one to the stadtholder. The States-General representing the provinces were, unlike the stadtholder and his sons, of the opinion that the Republic would stay neutral, so an army was not necessary. Even during the spring of 1792 when tension was rising, and in spite of the strongest remonstrances by Prince Willem of Orange, the States-General only agreed on the introduction of new drill-regulations for the infantry and the abolition of the parade-step! Only on 7 September 1792, after long deliberations, was an agreement reached about a resolution that laid down the strength for the Dutch army at 44,823 men. A large part of this Dutch army consisted of foreigners. For example of the infantry, only 26 out of 40 regiments were national. Even in these ‘national’ regiments, many foreigners were enlisted. The composition en strength of the Dutch army according to this resolution would be as follows: [6] 1) Staf van het leger (Staff of the army) The staff of the army consisted officially of the following numbers of officers, although as can be seen, in reality the amount somewhat differed:

2) Regimenten ordinair voetvolk (Infantry regiments) Although the regiments had a unit number, these were only used on their weapons and equipment. The regiments were known by the name of their commander (Colonel). A regiment was two battalions strong, each consisting of a grenadier company and six musketeer companies. The following infantry regiments existed at this time:

Oranje Vriesland Oranje Stad en Lande en Drenthe Oranje Nassau, No. 1 (German) Oranje Nassau, No. 2 (German) Erfprins van Oranje Nassau No. 1 De Schepper No. 2 Van Maneil No. 3 Van Dopff No. 4 d’Envie No. 5 Des Villates No. 6 Van Welderen No. 7 De Bons No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette No. 9 Van Randwijck No. 10 Van Brakel No. 11 Van Dam No. 12 Bedaulx No. 13 Von Quadt van Huchtenbroek No. 14 Hessen-Darmstadt (German) No. 15 De Petit No. 16 Von Mönster No. 17 Van Plettenberg No. 18 Van Pabst No. 20 Frederik Prins van Baden-Durlach No. 22 Van Nijvenheim No. 23 Stuart No. 24 Bentinck Vorst van Waldeck, No. 1 (German) Vorst van Waldeck, No. 2 (German) Saxen-Gotha (German) Nassau-Usingen (Walloons) 3) Waalsche infanterie (Walloon infantry)

4) Jagers (Jäger)

5) Garde-Zwitsers (Swiss Guards)

6) Regimenten ordinaire Zwitsers (Swiss regiments)

Regiment May Regiment Stockar de Neuforn Regiment Hirzel Regiment De Gumoëns 7) Korps Zee-officieren (Corps sea-officers)

8) Regimenten Mariniers (marine regiments)

No. 21 Westerloo The organisation of these regiments was the same as for the regular infantry. 9) Regimenten ordinaire ruiterij (Cavalry regiments)

Regiment Van Tuyll van Serooskerken Regiment Stavenisse-Pous Regiment Van Hessen-Philipstall Regiment Van der Duijn Regiment Hoeufft van Oijen 10) Regimenten Ordinaire Dragonders (Dragoon regiments)

Regiment Van Bylandt (Walloon) 11) Regiment Huzaren (Hussar regiment)

12) Regiment Artilleristen (Artillery regiment)

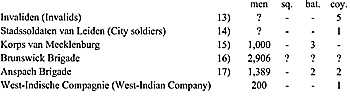

The above troops were not only to form a field army, but also had to garrison the about forty fortresses and in addition about eighty other cities and places. As may be clear, overall strength was much too small to fulfil this enormous task. Beside the units laid down in this resolution, the following units existed in the Dutch Republic, used for garrison duties:

13) Invaliden (Invalids)

14) Stadssoldaten van Leiden (City soldiers)

15) Korps van Mecklenburg

16) Brunswick Brigade

17) Anspach Brigade

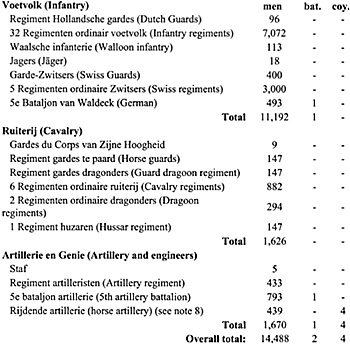

The events in the south, where Dumouriez quickly defeated the Austrians and advanced to the borders of the Dutch Republic, caused some people to believe that maybe it would be not possible after all to stay neutral any longer. Therefore, plans for an augmentation of the army were laid down before the States, on 31 December 1792 and 9 January 1793. The proposal was to strengthen the army with 13,260 men. When the augmentation was at last approved, on 6 and 21 February, war had already begun. With these additions, the army would be increased by 14,488 men, partly by strengthening the existing companies, partly by taking into service or raising units. According to the augmentation the Dutch army would be expanded as follows:

Where to find the men was the next problem; the infantry for example was already before the augmentation 2,500 men short! The cavalry was 1,000 horses short. The units lacked sufficient cartridges, cartridge boxes, and even muskets. [9] Recruitment was made even more difficult because a ‘fifth column’ consisting of patriots and foreigners tried to talk soldiers out of Dutch service by promising them better pay. This practice was quickly forbidden by penalty of death. The same occurred with horses. These were bought and sold in foreign countries, until huge fines countered this practice. [10] The field army would be led by the son of Willem V; Willem Frederik, hereditary Prince of Orange and Nassau (Prince William of Orange), the future King Willem I. The following measures were taken to form a field army. The grenadier companies were taken away from their parent units and converged into grenadier battalions. The musketeer companies of each regiment were combined into a battalion of eight companies and a weak depot. However, in practice most of these battalions were no stronger than six companies. Problems were so huge that bounties were offered to captains that would have brought their companies up to war footing in a certain term! Especially because of the lack of horses, the cavalry regiments in the field were initially not stronger then two squadrons each. The field artillery consisted of the newly raised horse artillery, four companies in all serving eight guns each. The field artillery consisted of 48 3pdr guns, of which two guns were attached to each infantry battalion. In addition, there were three batteries armed with 6pdr, 12pdr guns, and 24pdr howitzers. The number of horses and vehicles was however completely inadequate. Command of the artillery and the cavalry was given to the other son of Willem V; Willem George Frederik, Prince of Orange and Nassau (Prince Frederick of Orange). He received the title of ‘Grand Master of the Artillery’. Colonel Paravinci di Capelli assisted him. In spite of all measures, the Dutch army never reached it full strength of 3,230 officers, 54,853 others, and 6,557 horses. At the end of February 1793, strength of the field army did not exceed 16,000 men and 3,000 horses, insufficiently armed and equipped! Experience of these troops was low. Without counting the Prussian invasion of 1787, during which hardly or no real fighting took place, the army had not taken the field for 45 years. Practice had been limited to drill and parades, but no real preparation for war. Long marches were also not practised, so when the army took the field in 1793, every two or three days a resting day had to be held to allow the many stragglers to catch up with their parent units. Some regiments even forgot to take their colours into battle! Further, as we have already seen, especially with the infantry, many foreign units were part of the Dutch army. The most experienced were foreigners who had not much stomach to fight for the Dutch Republic, at least not without better payment. For these reasons, the States-General thought it much more efficient to use these for garrison duty, and to let the inexperienced national troops do the fighting. Perhaps surprisingly, the morale of the soldiers was not as bad as might be expected. Most soldiers serving involuntarily had already found a way to leave the Dutch army. The officer corps is an entirely different story. Most of them were of advanced age, with no experience in the ‘modern’ French way of doing battle. They were surprised by the ferocity of the French attacks, by their unorthodox tactics, and their - according to the standards of this time - quick advance. Therefore, they would be no match in the upcoming French advance, until they could regain their posture. The fortresses and other defence works were in a sorry state. Maintaining them had been completely neglected for years. The Prince of Hessen, who defended Maastricht -one of the strongest fortresses of the Dutch Republic- had only 4,800 men while he needed at least 10,000. Only 1,600 men defended Breda, while all fortifications of this city had fallen into decay. The governor of Geertruidenberg was eighty years old! There were more than enough guns available to arm all the fortresses but there were not enough gunners. Gorinchem for example, had less than fifty gunners to serve 150 guns. Initially, Heusden had none! During the siege of 1794, in this fortress fifty gunners, augmented by troopers of the cavalry regiment Van der Duijn served the guns. The state of the Dutch navy, at last, was a little bit better. During 1792, measures were taken to fit out the navy. After 1 December 1792, when armed French ships entered the river Scheldt and sailed to Antwerp, a squadron of small warships were stationed at the mouth of the river Scheldt, as we have already seen commanded by Captain Haringman. A Dutch squadron was recalled from the Mediterranean and reinforced him. When hostilities were commenced, he commanded a squadron consisting of a 64-gun ship of the line, five ships with 24 or 20 guns, one ship of 18 guns and one of 14 guns, twelve gunboats and more small armed ships. He was supported by the arrived British squadron commanded by Commodore Murray, consisting of a 4th Rate 50-gun ship, two 32-gun frigates, a ship of 28 guns, one of 18 and one of 16 guns. Vice-Admiral Jan Hendrik van Kinsbergen received overall command of the naval defences of the Dutch Republic. Declaration of WarAfter the declaration of war, at The Hague a council of war was being held to prepare for the defence of the Dutch Republic. Prince William of Orange, Vice-Admiral van Kinsbergen, Major General C.D. du Moulin (leading the defence of the fortresses), Secretary of State J.H. Mollerus, the ‘raadspensionaris’ (‘Counciller of State’) Mr. Laurens Pieter van de Spiegel, and others attended this council. It was agreed upon that Van Kinsbergen and Du Moulin would reconnoitre the southern part of the Dutch Republic, and propose a plan for its defence. The plan was presented during the last part of February, and approved. According to this plan, the following measures would have to be taken:

From the above measures, the following can be concluded. It was -- correctly -- assessed that the southern part of the Dutch Republic was under the circumstances not able to defend against a determined French attack. The decision was made to yield the terrain to them, except for some fortresses, which would be defended to hamper French movement and to force the enemy to use troops to blockade or besiege these. For this purpose, the most important fortress-cities Maastricht, Venlo, Grave, ‘s Hertogenbosch, Willemstad, and Bergen op Zoom were strengthened. Many other fortress-cities in the south, for example Klundert, Breda, Geertruidenberg, Gorinchem, and Heusden were thought to be strong enough for the moment, or of less importance, and only their garrisons were strengthened. The main defence would be behind the rivers Meuse and Waal where the French would have to use boats or bridges to cross. This would give the Dutch time to concentrate their troops on the threatened location, and would give the Dutch a chance to inflict heavy casualties with their batteries and naval forces. The French were expected to advance and attack somewhere between Beierland and Gorinchem. Zealand and the Scheldt estuary would be impracticable, because of the many waterways that would have to be crossed and the presence of the Dutch and British fleets. A French advance to the east of Gorinchem would be highly unlikely, because a French advance would be threatened in the right flank by the Austrian army. Furthermore, a French advance through these parts of the Dutch Republic would not threaten directly the most important part of the Dutch Republic, the province Holland with the cities Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, seat of the Dutch government. The weakness, especially of the infantry units, was also taken into account, thus the additional firepower of battalion and regimental guns. The necessity of taking good care of the scarce soldiers was met by adding surgeons to the units and the establishment of a general hospital. In addition, Colonel of the engineers Van der Graaf was instructed to prepare for defence the ‘Grebbe-line’, between the river Lek and the Zuiderzee. The Dutch navy defended the coastline and the Scheldt-estuary. There were however no ships to spare to defend the Hollands Diep and the rivers. So for this purpose all kinds of ships were hired and fitted out with cannon. Rear-admiral Melvill received command of the fleet on the Hollands Diep. The few boats already present here would be augmented to 32 in a few weeks. On 14 February, the inundation of several parts of the country along the rivers was ordered, around Gorinchem, and Heusden, and the region east of the Hollandsch Diep. More inundations were prepared in such a way that these could be made effective in a few hours. Its implementation received much resistance from the inhabitants, provoked at many places by the patriots. Prince Frederick of Orange received command of a small embryonic field army, consisting of national, Anspach and Swiss troops. This army assembled in the vicinity of the fortress-city Grave. After this meeting, Prince William of Orange left for Frankfurt, trying to get guarantees for military support if the Dutch Republic were to be attacked. Luckily, the Dutch would not have to fight alone. Of course, the Austrians and Prussians were already present in force along the Rhine. More about them in the following parts of the series. On the last day of February, the first British troops arrived at Hellevoetsluis. As already described, the British were fully aware of the dangers that a French capture of the Netherlands would bring for the safety of Britain. Therefore, there was no hesitation in sending troops. With them was the son of King George III; Frederick August, Duke of York and Albany, who would lead the British expeditionary force. Secret negotiations between the French envoy De Maulde; Lieutenant General Dumouriez; the British envoy in The Hague; and the Dutch Councillor of State Van de Spiegel were broken of on 13 February 1793. The French National Convention ordered Dumouriez to attack immediately. In the Dutch Republic, on 15 February the guard left ‘s Gravenhage for their destinations at the front: a musketeer battalion and two grenadier companies of the Regiment Hollandsche Gardes, and a detachment of the Garde-Zwitsers destined for Geertruidenberg; two squadrons of the Regiment Garde Dragonders destined for Steenbergen; and two squadrons of the Regiment Gardes te Paard destined for Raamsdonk. These troops had just enough time to reach their destinations, before the French attack came. However, the concentration of the field army would not even start until eight days later! Prince William of Orange returned from Frankfurt in a hurry to take command of the field army. It was clear that the Dutch were much too late with their preparations. Now the only thing they could do was trying to buy time…. Footnotes[1] It was the intermezzo between the patriots coming to power in the Dutch Republic and the subsequent Prussian invasion of Holland in 1787, and the creation of the patriot Batavian Republic after the French advance during 1793-1795.For details on the 1787 campaign, see my articles "The Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787", part I - IV, which appeared in First Empire No. 44 - 47 (1999).

BibliographyAa, Cornelis van der Geschiedenis van den jongst-geëindigden oorlog, tot op het sluiten van den vrede te Amiëns, bijzonder met betrekking tot de Bataafsche Republiek DI 1 (Amsterdam 1802)

More Part V: Intermezzo 1787-1793 The Dutch During the Revolutionary Wars

Battle of Swalmen, 1793 Part 12 [FE65] Defense of the Dutch Republic 1793 Part 11 [FE64] Siege of Willemstad 1793 Part 10 [FE63] Klundert and Willemstad 1793 Part 9 [FE62] Breda and Geertruidenberg 1793 Part 8 [FE60] Battle of Maastricht 1793 Part 7 [FE59] Austrian Troops and Dutch Defense Part 6 [FE57] Intermezzo 1787 - 1793 Part 5 [FE56] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part IV Part 4 [FE47] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part III Part 3 [FE46] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part II Part 2 [FE45] Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787: Part I Part 1 [FE44] Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #56 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2001 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||