The Prussians fought the early campaigns, including that of 1806, using the Reglement für die Königlich Preussichen Infanterie 1788 and Reglement für die Königlich Preussichen leichte Infanterie 1788. The Prussian Reglement of 1788 was essentially that of 1773, itself an evolution of those of 1743, 1748 and 1766. Although it has received considerable criticism, it was no more anachronistic than those of the Austrians and British. Further-more, the Prussian infantry was as well trained in the evolutions of their own regulations as most.

The Prussian infantry manoeuvred at 108 paces to the minute, like the British, in columns of half zug (half section), zug (section) or company. The musketeer battalion, established at four compa-nies in 1787, was reorganised into five companies in 1799. Grenadier battalions retained the four company structure. The tactical sub unit, however, was always the zug, of which there were two in each company, ten tactical sub-units in each line battalion exactly as we saw in the British service.

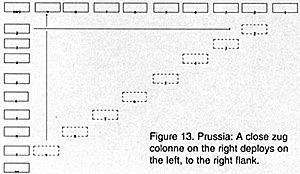

Deployment into three rank line was performed, outside the range of effective fire, from a closed zug colonne to either flank as required, on either the head or rear zug, by means of a flank march of sub-units in files "en tiroir", so called because the sub-units were pulled out of the column much as one might drawers from a chest, tiroir being the French for a drawer.

Deployment from close zug colonne formed on the right to the right flank required the rear, left flank, zug to stand fast whilst those in front executed a half pivot to the right and marched by file to the flank, halting in front of their appointed place in the line and making half pivot to the left. The rear zug had, in the meantime, been marching forward onto the position where the line was to deploy and halted. The remaining sub-units marched forward and dressed into line on it.

An illustration is at Figure 13. Inverted deployment to the left flank was allowed and was a mirror image. This is the 'en tiroir' innovation, identical to that used by deploying British columns of grand divisions and variations of which were adopted by the French, as seen already.

An illustration is at Figure 13. Inverted deployment to the left flank was allowed and was a mirror image. This is the 'en tiroir' innovation, identical to that used by deploying British columns of grand divisions and variations of which were adopted by the French, as seen already.

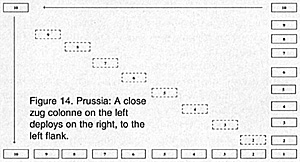

Deployment from close zug colonne formed on the left to the left flank required the rear, right flank, zug to stand fast whilst those in front executed a half pivot to the left and marched by file to the flank, halting in front of their appointed place in the line and making half pivot to the left. This placed them in the retired position. They then dressed into line on the right flank zug which had stood fast, performing a further pivot placing them back in the advanced position. An illustration is at Figure 14. Inverted deployment to the right flank was a mirror image.

The 'en tiroir' method of deployment perpendicular to the enemy line had been introduced into the Prussian army in 1752 as an alternative to the more common parallel deployment, in which an open zug colonne wheeled to the right, presenting its left flank to the enemy line, and then halted whilst the sub-units effected a 90 degrees left wheel into line. It was this method of deploy-ment which impressed Guibert.

The 'en tiroir' method of deployment perpendicular to the enemy line had been introduced into the Prussian army in 1752 as an alternative to the more common parallel deployment, in which an open zug colonne wheeled to the right, presenting its left flank to the enemy line, and then halted whilst the sub-units effected a 90 degrees left wheel into line. It was this method of deploy-ment which impressed Guibert.

The Prussian company column was formed on a double zug frontage and appeared identical to the British column of grand divisions already described. It was formed in similar manner and deployed as described above. The principal columnar formation in the Prussian service, however, remained the zug colonne Line to column conversion was achieved by having the sub-units make a left or right half pivot into column of files, to whichever flank the column was being formed on, and wheel by files back into position behind the stationary flank sub-unit, as has already been seen in the British and French service.

Musketry and assaults were delivered in three rank line although one of Ruchel's regiments at Jena was formed in two ranks. This, however, does not appear to have been the tactical innovation it is sometimes described as, for what Ruchel actually did was strip away the third ranks and form them into two additional extemporised battalions which were left as part of the garrison in Weimar. The result was that Infantry Regiment Treuenfels arrived on the field at Jena under strength and in an unfamiliar structure.

There is some evidence of manoeuvre columns being used tactically where ground precluded the deployment of lines, such as in villages. Assault columns, however, as understood by the Règlement of 1791, are not reflected in the Reglement of 1788 although Scharnhorst is clear that experiments had been made with them at least as early as 1804.

Each line infantry battalion initially provided ten rifle armed schützen from the third rank for skirmishing, increased to 50 schützen in 1799. The use of the entire third rank for skirmish-ing had already been given consideration but was not official practise, although at Jena there is at least one example of an entire company being deployed as skirmishers, repeated by elements of L'Estocq's Corps at Eylau. The deployment of entire companies in open order, however, must be considered the exception rather than the rule for the bulk of the rank and file were not expected to function in this way.

The Fusilier battalions, of which there were 27 battalions by 1800, retained the four company structure and were trained in both open and close order drill, hence the Reglement für die Königlich Preussichen leichte Infanterie 1788 which actually preceded those for the rest of the infantry by six months. Other than specifying two ranks as the normal formation, and giving some instruction for skirmishing, they differed hardly at all from those for the infantry as a whole.

The Offensive

If the Austrians were the epitome of 18th Century defensive tactical doctrine, the Prussians were the epitome of the offensive, exemplified by the famous echelon and oblique order. This, however, required very precise choreography and a high standard of individual training. It also required open terrain ideally, although the evidence of many of Frederick the Great's battles gives a lie to the belief that they were always fought over ground resembling a cricket pitch. Probably as important as anything else, however, was Frederick's cavalry, particularly in the later campaigns when the quality of his infantry had declined through casualties amongst the highly trained soldiers, a problem Napoleon was to encounter, increasingly from about 1807 onwards. It was the dominance of this arm that allowed the Prussian infantry to continue to manoeuvre as it did. By 1806, in terms of organisation and level of training, this vital ingredient no longer existed.

The Prussians emerged from the Revolutionary Wars with more success than they are generally credited and even during the 1806 campaign, at the tactical level, where battalion fought battalion on the line of battle, Prussian infantry does not seem to have been at any particular disadvantage and the concept that French skirmishing was a decisive factor by itself holds little, if any, water. The initial fault lay with strategic mistakes, the principal ones being, in very general terms, the failure to go to war in 1805 alongside the Austrians and Russian, and the erroneous belief the following year that Prussia was numerically strong enough to fight the French alone.

The felony was compounded by some examples of gross grand tactical ineptitude resulting, for example, in the piecemeal defeat of Hohenlohe's army at Jena, culminating in the destruction of Grawert's Division in front of Vierzehnheiligen. The catastrophic nature of the defeats at Saalfeld, Jena and Auerstedt might have been avoided had it not been not for serious defects in the Prussian command, control and grand tactical organisation, indeed, so extraordinary were Prussian movements before the battles that Napoleon was quite unable to interpret their intentions, a reflection of the failure of the Prussian command to agree. I think it was Clausewitz who commented that the only thing worse than dividing one's army in two in the face of the enemy, was dividing it in three.

It has been customary to attribute the scale of these defeats to 18th Century infantry tactics on the part of the Prussians. Whilst there is a grain of truth in this, it is a shallow inter-pretation of what actually took place and entirely ignores the blunders made at grand tactical levels of command which placed Prussian soldiers in impossible tactical situations. What the Prussian infantry were actually capable of when properly led was demonstrated at Eylau in 1807, where attacking Prussian regiments of L'Estocq's Corps handled the French very roughly indeed.

The Prussians grasped the tactical relationship between the skirmisher, column and line rather better than most and the resulting Exerzir-Reglement für die Infanterie der Königlich Preussischen Armee 1812, hereinafter the Exerzir-Reglement 1812, which replaced both 1788 reglements, is considered to be, not only the best, but also the most succinct infantry regulations to emerge from the period.

Reorganization

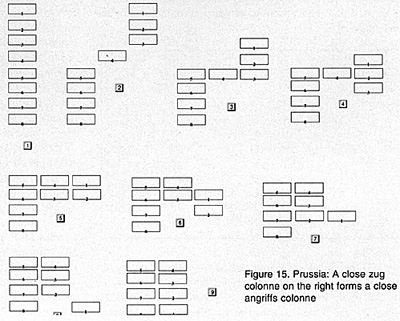

The reorganisation of 1808 reverted to a four company battalion throughout although the zug remained the tactical sub unit, of which there were now eight in each battalion. The Exerzir-Regle-ment 1812 retained the zug colonne, which deployed as it had done under the Reglement of 1788, and added the angriffs colonne, formed on a double zug (company) frontage, to the infantry's repertoire.

The angriffs colonne was the equivalent of the French colonne d'attaque formed in divisions, each consisting of two züge. The divisions of the Prussian column, like the French, were not all composed of the same züge as the divisions when in line. The leading division consisted of the 5th and 4th, as it did when in line, the second division, however, consisted of the 6th and 3rd züge, the third division the 7th and 2nd, and the rear division the 8th and 1st.

Deployment from angriffs colonne to line could be made on the centre to both flanks simultaneously, exactly like the colonne d'attaque. The leading division stood fast whilst each zug behind it made either a left or right pivot and marched in column of files to the left or right flank, halting opposite its place in the line. Each then made a right or left pivot and marched forward, dressing into line on the leading division.

The conversion from zug colonne to angriffs colonne was complex and no equivalent existed in the French service. It was performed on the 4th zug and involved the leading züge marching to the right and to the rear in order to assume their positions in the line. An illustration is at Figure 15.

The conversion from zug colonne to angriffs colonne was complex and no equivalent existed in the French service. It was performed on the 4th zug and involved the leading züge marching to the right and to the rear in order to assume their positions in the line. An illustration is at Figure 15.

Formation of angriffs colonne from line was achieved by means of a left or right half pivot and a wheel by files back into position behind the centre division of the line exactly as in the French service. The column of divisions formed of the right or left flank division was not used.

The Exerzir-Reglement 1812 implies the deployment of manoeuvre and assault columns into line for combat but interpretations of its use during the latter campaigns of the period, have concluded that the Prussians sometimes used the angriffs colonne as a tactical formation. If correct, the reason may have in part been the inexperience of some Landwehr and Reserve regiments and doubts about their ability to convert from column to line under fire. It may also be that many of these examples were cases of the angriffs colonne not needing to deploy. Although conjecture, I prefer the latter explanation simply because columns generally do not have a very good track record against steady formed infantry lines.

The Prussians, uniquely as far as I know, also abandoned the use of the hollow square under the Exerzir-Reglement 1812. In its place they introduced a closed version of the angriffs colonne, in which the column halted, the ranks closed right up and the left and right files faced to their respective flanks. The inference of this is that the Prussians must have used the angriffs colonne as the principal manoeuvring formation on the battlefield because there was no longer any means of formal defence against cavalry whilst in zug colonne, other than converting to angriffs colonne and then closed square, the time penalty for which must have been unacceptable.

The Prussians continued to use specialist light troops in the form of Jäger, Schützen and Fusilier battalions. Although the last had now become the third battalions of the line regiments, they remained light infantry intended to fight in either open or close order. Additional skirmishers were provided from the third rank of musketeer battalions but by 1813 the Prussians possessed universal infantry generally, fully capable of functioning in formed or light roles and there are sufficient examples of entire battalions, even of Landwehr and Reserve infantry, deploying as skirmishers to suppose that all Prussian infantry was competent to a degree in both disciplines.

Prussian infantry used the entire repertoire of Napoleonic infantry tactics throughout the final, and decisive, campaigns of the period in Germany and France, column for manoeuvre and advance to contact, line for fire and assault, and skirmishers. Whilst they embraced the tactical flexibility and offensive doctrine of Napoleonic warfare, probably more completely than any other of the Allied countries, I think it is fair to say that they did so without quite the same degree of flair as the French themselves.

More Columns

-

Basics, Drill, Tactics, Doctrine, and Practice

Regulations and Tactics: Britain

Regulations and Tactics: France

Regulations and Tactics: Prussia

Regulations and Tactics: Austria

Regulations and Tactics: Russia

Corrections and Errata: Letter to Editor (FE18)

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #17

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com