In the Austrian service the infantry fought under the Exercitium für die sämmentliche Kaiserlich-Königlichen Infanterie, Generals-Reglement 1769, hereinafter the Generals-Reglement 1769, until 1807. Although I have only seen minor parts of this document in translation it has the reputation of being over-complex, even by the standards of the 18th Century. It was cer-tainly the most venerable infantry regulation used during the Napoleonic period. As far as the basic evolutions were concerned, nevertheless, it was not significantly different in concept to any of its peers. Sometimes called the 'Lacy Regulations', it was really Lacy's so called cordon system, a tactically defensive doctrine intended to counter the Prussian echelon and oblique order, for which he should really be credited, the Generals-Reglement 1769 was a virtual repetition of those of 1749 and as far as drill was concerned Prussian in all but name.

The infantry battalion was organised in 6 companies, each divided into two züge which were the basic tactical sub-units. It manoeuvred in columns of either zug or company, predominantly the former, and deployed by means of parallel deployment which, it seems, was preferred to the faster perpendicular method.

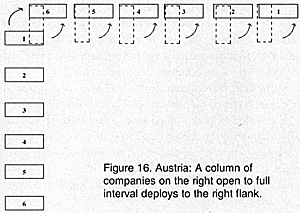

An illustration is at Figure 16. The three rank line was the principal tactical formation for both musketry and assault.

An illustration is at Figure 16. The three rank line was the principal tactical formation for both musketry and assault.

The Exercier-Reglement für die Kaiserlich-Königliche infanterie 1807, hereinafter the Exercier-Reglement 1807 replaced the Gener-als-Reglement 1769. It did not incorporate the divisional assault column in the French manner but confirmed the use of the third rank as skirmishers, a practise which had already started to evolve, and devoted a proportion of its content to open order functions.

The brief existence of specialist light infantry battalions, of which 15 were raised in 1798 and disbanded in 1801, meant that other than the numerically insignificant, though excellent, Tyroler Jäger Regiment, the Feldjäger and the Grenzer Regiments, which had become neither fish nor fowl, the Austrian army was not as well provided for in this context as it might have been. A contrast to the reputation held by Austrian light troops during the Seven Years War.

Incorporating much of Mack's Instructionspunkte für die gesammte Herren Generals der Kaiserlich-Königliche Armee of 1794, which was never officially adopted although an attempt was made in some haste, but far from universally, in 1805, the Exercier-Reglement 1807 retained the six company battalion organisation through the period, and beyond. The basic tactical sub-unit also remained the zug, with manoeuvre being carried out in zug and company columns at 105 paces to the minute.

Deployment from open company column was to the right flank when formed on the left. The leading, left flank company stood fast whilst those behind executed a quarter pivot to the right and marched diagonally to their places in the line, where they per-formed a further quarter pivot to the left to face their front.

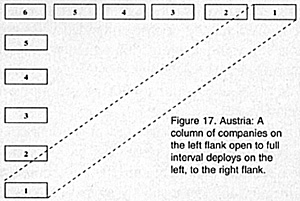

An illustration is at Figure 17. When the column was formed on the right, the method of deployment was on a centre company to both flanks, similar to that used by a British column of subdivisions. The centre company stood fast whilst those behind it deployed on it to the left flank as described above, by means of a quarter pivot and diagonal march. Those to the front, however, had to march backwards into line and to do so they executed a pivot placing the companies in the retired position. They then marched diagonally into place in the line at which point they were still retired and performed another pivot to bring them back into the advanced position. Zug columns deployed similarly

An illustration is at Figure 17. When the column was formed on the right, the method of deployment was on a centre company to both flanks, similar to that used by a British column of subdivisions. The centre company stood fast whilst those behind it deployed on it to the left flank as described above, by means of a quarter pivot and diagonal march. Those to the front, however, had to march backwards into line and to do so they executed a pivot placing the companies in the retired position. They then marched diagonally into place in the line at which point they were still retired and performed another pivot to bring them back into the advanced position. Zug columns deployed similarly

Formation of column from line was performed the same way in reverse of that described above.

Two other columns need to be examined. Both were essentially manoeuvring closed squares designed to counter cavalry, whilst affording a degree of movement not possible with an open square.

The first was the bataillonsmasse, simply a closed column of companies.

The other was the divisionsmasse which took one of two forms. The first consisted of three companies formed in closed company column, the second consisted of two companies formed in closed zug column. Thus, the battalion could provide either two or three small closed columns that operated separately from each other, but not so far apart that they could not deploy together into a single line.

The bataillonsmasse is said to have been used regularly, includ-ing for the advance to contact, becoming, to all intents and purposes, the Austrian equivalent of the divisional manoeuvre column. The divisionsmasse, on the other hand, appears to have been less popular.

The divisional column on the centre in the in the style of the French colonne d'attaque or Prussian angriffs colonne, did not exist.

The divisional column on the centre in the in the style of the French colonne d'attaque or Prussian angriffs colonne, did not exist.

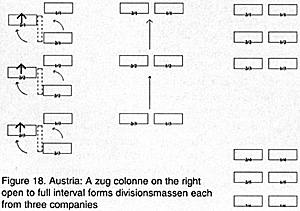

Formation of a three-company divisionsmasse from open zug column was achieved by alternate züge wheeling first to the left and then to the right, followed by a forward march until the ranks were closed right up. This would proved two divisionsmassen one behind the other, only one is illustrated. An illustration is at Figure 18.

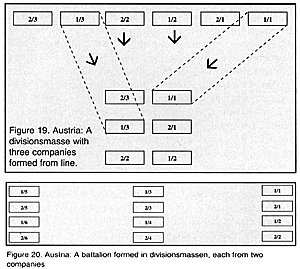

Formation of divisionsmasse from line required the centre divi-sion to pivot and retire sufficiently to make room for the remaining sub-units to form on its front. The immediate flanking companies moved next, executing a pivot followed by a diagonal march into position in the column. The extreme flanking companies moved next in similar fashion.

An illustration is at Figure 19. This does not bear comparison with equivalent conversions used by the French and others.

An illustration is at Figure 19. This does not bear comparison with equivalent conversions used by the French and others.

Formation of a two-company divisionsmasse was achieved simply by having the respective züge close right up into three individual divisionsmassen. An illustration is at Figure 20.

The three rank line continued to be used for musketry and the assault.

Although the Austrians exhibited more tactical versatility in the latter part of the period, they did not adopt the flexible concepts of Napoleonic warfare as enthusiastically as they might. The Exercier-Reglement 1807, to quote Krieg 1809, retained many of the "artifices of Frederician drill", an accusation which could be levelled at many, if not all, Napoleonic regulations to one degree or another, and one which has been interpreted as evidence that the Austrians continued to use the rigid linear tactics of the previous Century. This is not correct. As I hope I have already established, 18th Century regulations do not necessarily mean 18th Century tactics and a cursory examination of Austrian tactics at Aspern-Essling and Wagram reveals that the precise choreography of 18th Century linear infantry tactics had been abandoned.

Whilst it is true that the Exercier-Reglement 1807 was probably the most unusual of neo-Napoleonic regulations it was not the 18th Century document it is sometimes represented to be. On the other hand, the use of quarter pivots and diagonal marches for deployment, rather than a half pivot and flank march by files, or simple 45 degrees wheel, introduced unnecessary complications to what were comparatively simple conversions elsewhere. This could hardly be calculated to encourage tactical flexibility. Although the basic evolutions were similar to those used by the French and Prussians during the latter part of the period, the ways in which they were executed were eccentric.

More Columns

-

Basics, Drill, Tactics, Doctrine, and Practice

Regulations and Tactics: Britain

Regulations and Tactics: France

Regulations and Tactics: Prussia

Regulations and Tactics: Austria

Regulations and Tactics: Russia

Corrections and Errata: Letter to Editor (FE18)

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #17

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com