Although provisional regulations appeared subsequent to it, the French infantry used only one basic document throughout the period, the Règlement concernant l'exercise et les manoeuvres de l'infanterie du premier août 1791. These regulations had their origins in a work by the Comte de Guibert, Essai General de Tactique, published in 1770 and far from being a revolutionary work, it espoused all that was best in the Prussian regulations of the day, indeed it was in large part inspired by them, particularly the principal of deploying from column of companies perpendicular to the enemy line 'en tiroir'.

It has been claimed, but not by Guibert himself, that he was the first to recognise the advantages of the perpendicular flank march of files for deploying a column on the head but, as we will see, the Prussians had been using it since 1752. What he did advocate, however, was that the column should be allowed for assault as well as manoeuvre. This needs qualification for it has been interpreted as a column designed to function as an instrument of shock, but there is no evidence that Guibert ever intended the assault column as such. It is perfectly clear that the assault columns advocated by Guibert were ones of manoeuvre, but ones intended for the advance to contact at which point they were to deploy. This was in contrast to manoeuvre columns elsewhere at the time, which deployed well outside the range of effective fire.

He defined their advantages as rapidity of manoeuvre over ground which might be difficult for the line and as having certain morale benefits, adding confidence to one's own troops whilst intimidating the enemy. He was also aware that the column had a number of disadvantages which he gave as a tendency to disorder under fire when the natural instinct of men was to crowd together, a factor also evident even when a position was carried by a column, which made it vulnerable to counter attack. He was also of the view that, contrary to popular belief, a column was harder to control than a line as it was more difficult to convey orders in the former, which also made it harder to rally.

Guibert advocated that columns and lines should be used in combi-nation, in accordance with tactical circumstances for which there were no doctrinaire solutions. The essence of his concepts was speed of manoeuvre and conversion from one formation to another. Perhaps as important as anything, it was his view that all infantry should be capable of fighting in either close or skirmish order.

Three Rank Line

Despite such innovations, Guibert retained the three rank line as the principal tactical formation for formed infantry. During the latter part of the 18th Century there was much debate in France over the respective advantages of linear and columnar tactics, the result of which was no less than 11 provisional règlements between 1750 and 1791. That of 1764, however, was the basis for all those which followed, culminating in, after considerable experimentation, the Règlement of 1776. This document remained essentially linear but conceded that columns, of either peleton (company) or division (double company) frontage, could be used for assaults where circumstances dictated.

According to Duruy, the Règlement of 1791 was virtually a repeti-tion of the Règlement of 1776. Not having seen a copy of the latter, I cannot confirm this except to say that I do know that the, very small, part of the former dealing with skirmishing is said to be lifted from the latter verbatim.

The Règlement of 1791 allowed manoeuvre columns on peleton and division frontage, conversions being carried out at 120 paces per minute. Prior to 1808, the battalion consisted of nine peletons, one of which was the grenadier peleton, usually detached to form composite grenadier battalions, and another, after 1804, the voltigeur peleton. As is well known, the Règlement of 1791 illustrates an eight peleton battalion throughout.

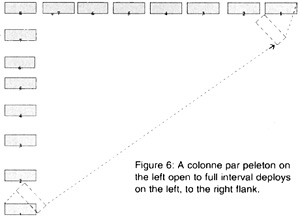

Deployment from colonne par peleton to a flank was executed on the head, which could be either the left or right flank peleton, from a column open to full interval. The leading peleton re-mained stationary whilst those behind it made a 45 degrees wheel to the right followed by a diagonal march to their place in the line, dressing into position by means of a further 45 degrees wheel to the left. An illustration is at Figure 6.

Deployment to the left flank would be a mirror image and normally conducted from a column formed with the head on the right flank peleton.

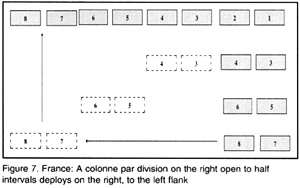

Deployment from colonne par division could also be executed to either flank but by means of a variation of the 'en tiroir' manoeuvre. Each division made a half pivot to the deploying flank and marched in file to the place opposite their position in the line, made a further half pivot and marched forward dressing into line on the leading division of the column which had stood fast. An illustration is at Figure 7.

Here we see a colonne par division formed on the 1st division, consisting of the 2nd and 1st peletons, deploying to the left flank. Deployment to the right would have been a mirror image with the column formed on the 4th division.

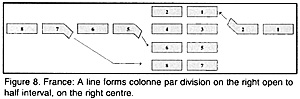

Conversion from line to column was achieved by the simple expe-dient of having soldiers in the sub-units execute a half pivot and wheel in file back into position in the column. This could be executed on any sub-unit, the one in question standing fast whilst the remainder formed on it.

An illustration is at figure 8 showing a line forming colonne par division on the 2nd division.

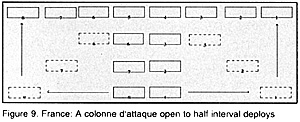

The colonne par division with its head on the centre division was known as the colonne d'attaque.

Deployment from colonne d'attaque was also by means of the flank march of files, already described, but to both flanks at once. An illustration is at Figure 9.

Although deployment from colonne d'attaque was faster because the longest distance travelled by any sub-unit was shorter than in a column formed on a flank division, it is very possible that it was actually used less than is usually imagined. The reason for this is simple.

Battalions approached the battlefield in columns of route, forming into manoeuvre colonnes par peleton as they got close. A colonne par division could be formed from colonne par peleton, right in front for example, by having the even numbered peletons march to their left flank by files and dress forward onto the odd numbered peletons, as already described for forming a column of grand-divisions in the British service. This would result in divisions, front to rear, formed from the following peletons, 2nd and 1st, 4th and 3rd, 6th and 5th and 8th and 7th.

The colonne d'attaque, other than the leading division, consisted of divisions composed of different peletons from those of the divisions of the line, front to rear 5th and 4th, 6th and 3rd, 7th and 2nd and 8th and 1st. This was necessary in order to maintain linear hierarchy when the colonne d'attaque deployed. Thus, under the Règlement of 1791 the only way to form colonne d'attaque was via line. The colonne par peletons had first to deploy into line and then form into colonne d'attaque, all of which required time and space, the latter, incidentally, being a much overlooked factor in the context of the examination of conversions.

Furthermore, It is also the case that when the Voltigeur company is detached, colonne par division, of any type, is impossible because the battalion is reduced to an uneven number of peletons. When a company was detached, the Règlement of 1791 prescribed colonne par peletons. The logical upshot of this must be that either entire battalions were earmarked for skirmishing whilst others remained formed, or that colonnes par peletons were used much more than is realised. The custom of having an entire sub-unit in the light role is clearly less good that in the Prussian and Austrian services where each sub-unit earmarked its third rank as skirmishers, thus avoiding disruption of battalion symmetry when they were detached.

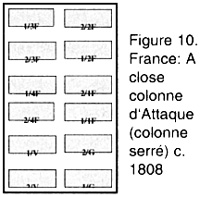

The reorganisation of 1808 resulted in a six peleton battalion, the 1st being the grenadier and the 6th the voltigeur. With the change of size of the individual peleton, the division became that of a single peleton divided into two sections, producing 12 tactical sub-units. An illustration is at Figure 10.

The reorganisation of 1808 resulted in a six peleton battalion, the 1st being the grenadier and the 6th the voltigeur. With the change of size of the individual peleton, the division became that of a single peleton divided into two sections, producing 12 tactical sub-units. An illustration is at Figure 10.

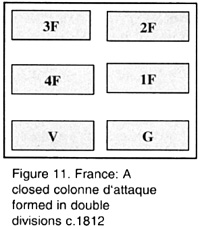

The most common columnar formation from this later period however, dating from approximately 1812/1813, appears to have been one of double division frontage, representing a reduction in depth to nine ranks plus intervals, and is the formation most frequently illustrated by modern commentators. This does not exist as such in the Règlement of 1791. An illustration is at Figure 11. Despite these changes, the methods laid down in the Règlement of 1791 were unchanged.

In late 1813, prior to the Battle of Leipzig, it was ordered that the infantry should form in two ranks but it is not clear to what degree this was applied, if at all. This increases the frontages of division and double division columns to and 143 and 286 feet respectively and represents an even more marked tendency towards a linear rather than columnar formation, with all the difficulties associated with lines in the context of poorly trained troops, which is what a significant part of the French infantry was at this time. It would not appear, therefore, that the double division frontage column, especially with sub units formed in two ranks, was a particularly appropriate arrangement for most of them.

In late 1813, prior to the Battle of Leipzig, it was ordered that the infantry should form in two ranks but it is not clear to what degree this was applied, if at all. This increases the frontages of division and double division columns to and 143 and 286 feet respectively and represents an even more marked tendency towards a linear rather than columnar formation, with all the difficulties associated with lines in the context of poorly trained troops, which is what a significant part of the French infantry was at this time. It would not appear, therefore, that the double division frontage column, especially with sub units formed in two ranks, was a particularly appropriate arrangement for most of them.

Despite the apparent disadvantage of lines, multi-battalion columns, apparently composed of a number of battalions deployed in line, usually supported by others formed in column, had al-ready started to appear in the French repertoire. MacDonald's at Wagram and d'Erlon's at Waterloo are typical although the precise nature of the latter has been subject to some conjecture. In the case of the former, however, there is primary evidence which shows that the leading regiments were formed in two lines of deployed battalions, that is to say four battalions, in three ranks, in each, supported by battalion columns. Although given the name 'column', it is hardly an accurate description for this is clearly a linear grand tactical arrangement.

Returning to battalion columns, the evidence of the Règlement of 1791 really leaves no doubt whatever that the French colonnes par divisions were non-tactical formations intended for manoeuvre only. That they were intended for manoeuvre under fire, the advance to contact, is clear and this was a departure from earlier practice, but it is also very clear that they were intended to deploy into line for combat once contact had been made. They were, therefore, non-tactical formations.

It is unfortunate that Oman's analysis of French use of manoeuvre columns in the Peninsula, has left an impression of columnar shock tactics. This analysis was accepted, virtually without question, by generations of historians from Fortescue to Weller. More recent analysis, however, has left little doubt, that on contact with the British line, the French frequently attempted to deploy battalion manoeuvre columns into lines. The combination of surprise, musketry at close range and vigorous counter attack, either prevented deployment of the column or defeated it before deployment was even attempted and, thus, unable to use its weapons, the non-tactical formation was destroyed by the tactical one using, essentially, what were 'ambush' tactics.

Following on from Oman's analysis, however, since musketry was not an issue apparently, at least as far as the French were concerned, it became received wisdom that they were massive closed columns which, moreover, are frequently interpreted as a solid block of men. This too is almost certainly wrong.

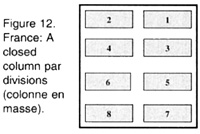

The Règlement of 1791 allows closed, quarter, half interval and full interval columns. The close column, or colonne serré however, is illustrated at quarter intervals, that is to say, the interval between succeeding sub-units is one quarter of their width. This is repeated by Colin. French divisional manoeuvre columns were not necessarily a phalanx like formation, as illustrated by David Kilburn in his letter in First Empire No 12. This is the closed column, the colonne en masse, essentially a closed manoeuvring square. An illustration is at Figure 12.

Further evidence that colonnes par division were not necessarily the solid mass they are often portrayed as, may be found in Ney's instructions to his VI Corps in 1805 where he amplifies the Règlement of 1791 in the context of open squares. Ney recognised that there might not be sufficient time for a "column with intervals by peletons or divisions" to form an open square, from which it is possible to infer that manoeuvre columns were usually open to one degree or another. In such a case he ordered that they "close up in mass", the flanking three files half pivoting to form the left and right face of the extemporised closed square, the rear division executing a pivot to form the rear.

Further evidence that colonnes par division were not necessarily the solid mass they are often portrayed as, may be found in Ney's instructions to his VI Corps in 1805 where he amplifies the Règlement of 1791 in the context of open squares. Ney recognised that there might not be sufficient time for a "column with intervals by peletons or divisions" to form an open square, from which it is possible to infer that manoeuvre columns were usually open to one degree or another. In such a case he ordered that they "close up in mass", the flanking three files half pivoting to form the left and right face of the extemporised closed square, the rear division executing a pivot to form the rear.

The Règlement of 1791 did not reject the linear regulations of the 18th Century. On the contrary, the only formation and con-version that would have been wholly unfamiliar to any Prussian soldier of the previous century would have been the divisional manoeuvre column in the context of deployment on the centre exemplified in the colonne d'attaque. He would, on the other hand, have been quite unfamiliar with French tactics. It was not the letter of the regulations that was particularly differ-ent, but the way in which they were applied.

Rather than choosing ground to suit the formations, thus restricting tactical methods to a minimum, as had been the norm previously, French infantry formations were chosen in accordance with the ground as it happened to be, indeed, in accordance with tactical circumstances as a whole. The commander at tactical level was able to choose whatever formation he saw fit, so long as it was appropriate to his particular situation or mission. It was, in other words, tactics and doctrine that set the French apart.

More Columns

-

Basics, Drill, Tactics, Doctrine, and Practice

Regulations and Tactics: Britain

Regulations and Tactics: France

Regulations and Tactics: Prussia

Regulations and Tactics: Austria

Regulations and Tactics: Russia

Corrections and Errata: Letter to Editor (FE18)

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #17

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com