The British Rules and Regulations for the Formations, Field Exercise, and Movements of His Majesty's Forces 1792 is very well known and remained in use, without substantial change, throughout the Napoleonic Wars and beyond.

The British army immediately prior to the turn of the century was, without doubt, one of the most wretched in Europe. It was wanting in almost every respect. The early campaigns, such as that in Low Countries, were lack-lustre in the extreme and the army that emerged from them was held in contempt by both friend and foe alike, at home and abroad

Such was the state of the British army that other than comparatively minor expeditions, with mixed results, it was simply not fit to take the field on mainland Europe with any hope of seri-ously influencing events until 1809, even Wellington's successful campaign in northern Portugal in 1808 achieved little militarily in the greater scheme of things.

Consider in comparison what had been happening in central Europe, both in terms of numbers involved and effect. In 1809, the same year that a British army was ejected from Spain at Coruna and another forced to withdraw from the Continent after the ill fated Walcheren expedition, vast French and Austrian armies clashed in the main theatre along the Danube where, although ultimately victorious, Napoleon himself was administered his first signifi-cant set-back at Aspern-Esling.

Glover identifies three areas of special neglect. The first was the lack of uniform regulations, the second was false doctrine resulting from experiences in America, and the third was an incompetent and negligent officer corps. That these should have been successfully addressed was due to two men, David Dundas, whose Principles of Military Movements became the Rules and Regulations of 1792, albeit in somewhat abbreviated form, and The Duke of York, the army's great reforming administrator, who ensured that they were adopted by the army as a whole in 1795.

It is well known that Dundas attended Prussian manoeuvres in 1785 and although he claimed that his Principles of Military Movements was based on his own experiences, of which it is true that he had sufficient to qualify him, there are close similarities between many of the evolutions in the Rules and Regulations of 1792 and the Prussian Reglement of 1788.

For tactical purposes a British battalion was organised in ten companies, identical in appearance to the five company Prussian battalion in 1806, with its ten tactical sub-units, which will be examined later. The Rules and Regulations of 1792 specify manoeuvre columns of platoon, subdivisions (company) and grand divisions (double company). These are identical to the Prussian columns of half zug, zug and company under the Reglement of 1788. Conversions were carried out at 108 paces to the minute, which was also the same as the Prussians.

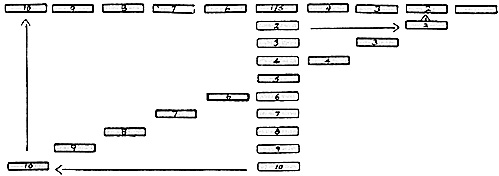

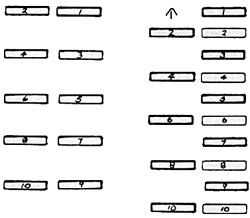

Deployment from close subdivision column was by means of flank march by subdivisions in column of files in a variation of the 18th Century Prussian "en tiroir" innovation. When deploying on the right centre, that subdivision stood fast whilst the soldiers in those to its front and rear executed a half pivot, right and left respectively, marched to the flanks in files halting opposite their places in the line and made a further half pivot left or right towards their fronts.

The leading, right flank, subdi-vision of the column now marked the extreme right flank of the line and now stood fast whilst the others dressed forward into line on it. An illustration is at Figure 1 (above). Deployment on the left or right flank sub-division was accomplished in similar fashion and is described later when examining the Prussian Reglement of 1788.

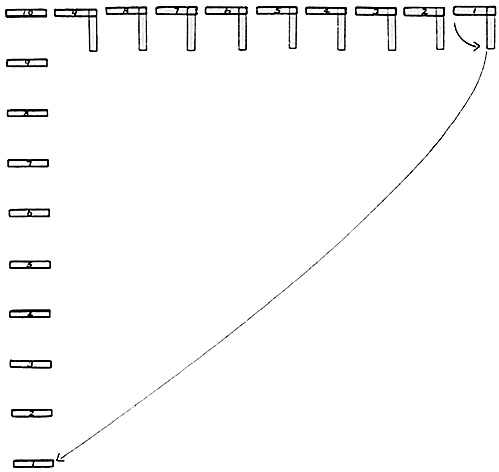

When a line converted to column it did so into open column of subdivisions at full interval, that is to say the distance between each subdivision was equal to the width of a subdivision, or into close column of subdivisions at half interval where the distance between subdivisions was approximately the width of a platoon.

Conversion from line to open column of subdivisions on the left flank, was achieved by having the left flank subdivision stand fast whilst the remainder were retired by means of a pivot. The subdivisions then executed a 90° left wheel towards the right flank, followed by a half pivot to their right and wheeled in files into place behind the left flank subdivision.

An illustration is at Figure 2 (above). Conversion could also be made on the right flank in mirror image of that shown.

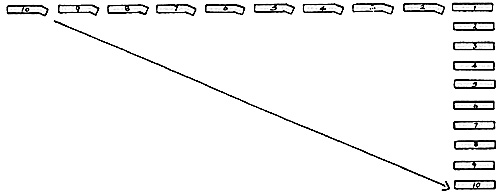

Conversion from line into close column of subdivisions on the right flank was achieved by having the right flank subdivision stand fast whilst the remainder made a half pivot to the right, whereupon the subdivisions marched by file diagonally into place in the column.

An illustration is at Figure 3 (above). Conversion could be made on the left flank similarly.

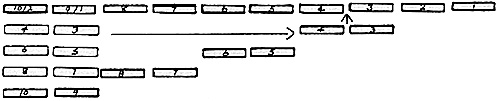

Deployment from column of grand divisions into line was perpendicular to the right flank 'en tiroir' as in the Prussian service. The rear, left flank, grand division stood fast whilst those ahead of it executed a half pivot to the right and marched in files to the right flank, halting opposite their places in the line and making half pivot to their left, thus advancing them. The leading, right flank, grand division of the column, now on the right flank of the line remained stationary whilst the others dressed forward into line on it. An illustration is at Figure 4 (below).

Column of grand divisions was formed from close column of subdivisions. The even numbered subdivisions executed a half pivot to the left and marched to the left one interval, made a further half pivot to the right and dressed forward onto the uneven numbered subdivisions. Despite a double company frontage, the column of grand divisions was not the equivalent of the French colonne d'attaque, as it is often represented to be, but the equivalent of the Prussian company column under the Reglement of 1788.

An illustration is at Figure 5 (above).

The British used both open and closed squares, the latter essentially a closed column of grand divisions. Squares, however, are beyond the scope of this article.

Other than the light companies of the line battalions, the British army had no light infantry at the outbreak of the Revolutionary Wars. By 1797, however, the 5/60th Regiment had been raised, followed by 6/60th and 7/60th in 1799. In the following year an experimental rifle unit was also raised, becoming the 95th (Rifle) Regiment of Foot in 1802 with, eventually, a strength of three battalions.

By 1803, three light infantry regiments existed. The first was the 90th Regiment, although it played little part in the Napoleonic Wars. This was followed by the 43rd and 52nd Regiments, the 68th Regiment in 1808, the 51st and 85th Regiments in 1809 and 71st Regiment in 1810. Exactly like the Prussian fusiliers, British light infantry battalions were expected to fight in either closed order as conventional infantry, or skirmish order. These units were trained under the Regulations for the Exercise of Riflemen and Light Infantry and Instruction for

their Conduct in the Field of 1798, a translation of a work by the Austrian officer, de Rottenberg and Instruction concerning the Duties of Light Infantry in the Field, by Francis Jarry, published in 1803, both of which amplified the nine pages devoted to subject by Dundas.

Although the Light Division was to become one of the finest fighting Formations of any army during the period, the fact is that the British army was never numerically strong in light infantry and it is fortunate that the Peninsula army had the services of numerous foreign light infantry units, some of which, such as those of the King's German Legion and the Portuguese Cacadores were examples of light units at their very best. There is, nevertheless, little doubt, that without the nucleus provided by the British army in general, there would have been no allied army in either the Peninsula or in Belgium.

The custom of creating specialist light and rifle battalions followed that established in Prussia and Austria. It was in contrast to that of the French whose philosophy was the universal infantryman. I don't think that Tim Franklin's view that "only the British seem to have recognised the importance of skirmishers in the French system" really stands up to much examination.

The question of British tactical doctrine has been the subject of intense debate by others far more qualified than I, more or less since Oman put forward his, now disputed and generally accepted as flawed, British firepower over "monstrous" French column theory in the twenties. Be that as it may, British tactical practice is, to all intents and purposes, the story of the two rank line, moreover, it is frequently, though incorrectly, asso-ciated uniquely with Wellington. It is quite clear that it had been in general use for some time before he rose to a position of prominence in the British army.

It has been said to the effect that British tactics and doctrine, because their infantry regulations did not lend themselves to any other, were almost always defensive. It is a matter of fact that most of Wellington's battles were fought on the tactical defen-sive, but it is also true that, as Wellington pointed out, were the Peninsula army to be destroyed there was little hope, if any, of it being replaced. He was, in other words, not in a position to take great risks with it.

On the other hand, although the victory at Salamanca was in part due to the celebrated cavalry action in which Le Marchant was killed, and the French loss of both their commander and second in command at approximately the same time, which caused a critical breakdown in command, it is also evidence that British infantry was perfectly capable of the tactical offensive when required.

The attack by Pakenham's 3rd Division was conducted initially in column, converting on the march at 250 yards from the French into three lines of deployed battalions. That by Leith's 5th Division in two lines of deployed battalions. The former was a morale victory, the French breaking before fire had been exchanged or physical contact made, the latter a combination of the physical and morale, being decided by musketry followed by a charge.

The attack of Pack's Portuguese Brigade on the Greater Arapil was in column and convincingly repulsed by the musketry of French infantry deployed just behind the crest, who fired and charged with bayonet in a direct reversal of the usual Peninsular scenario.

Even at Salamanca, however, Wellington was in his usual defensive posture initially, using ground to conceal his forces. When Marmont extended his left flank, Wellington grasped the opportu-nity and switched to the tactical offensive destroying him piece-meal.

Despite Wellington's record, the Rules and Regulations 1792, make no mistake, came out of exactly the same mould as those used by the central European armies so conclusively defeated between 1805 and 1806. Surely then, that which is held to be an anachronism in Thuringia must be equally anachronistic in Iberia. On the contrary though, it is also received wisdom that the British inflicted defeats on the French by virtue of their linear doctrine which, we are now told, bestowed the advantage of superior firepower and is exemplified as the appropriate counter to the French columns which now become massive, clumsy, unimaginative and all the other hard things that are said about them.

So, we now have a British army, whose infantry are trained in regulations similar, identical in parts, to those used by the Prussians at Jena, I will concede that the former's do have illustrations but apart from that and the language there is not much to choose between them, consistently defeating a French army whose infantry were trained in regulations and used tactical doctrine, which are held, other than in Spain, Portugal and Belgium apparently, to be part and parcel of the alleged revolutionary methods brought by Napoleon to 19th Century warfare.

Whatever else one says about Wellington, and he does not come over as a sympathetic character, one cannot overestimate his contribution as a leader, by which I mean his ability to motivate his soldiers, not all of whom were British by any means. What, I wonder, would history have to say about the British infantry and its regulations had Arthur Wellesley's mother not decided that the army was the only place for her "awkward son".

In Wellington, perhaps more importantly, the army also had one clearly identifiable, determined and ruthless chief who was sufficiently geographically distant from London that he could do, more or less, as he wanted without fear of immediate political interference, and certainly without question or debate from his subordinates. Contrast this with the 'command by committee' method that blighted the other allied armies, particularly in the early campaigns and, indeed, the sometimes behaviour of the Peninsular marshals. I digress.

I return to my opening preamble in which I said that regulations and tactics are not the same thing. Although the infantry drill contained in the British Rules and Regulations of 1792 was very similar in concept to the Prussian Reglement of 1788, the way in which it was applied on the battlefield was utterly different. The issue, at the risk of becoming repetitive, was a matter of tactics, not regulations.

British line was nothing like so rigid as the 18th Century Prussian in so far as precise dressing of and between units was unimportant in comparison. Quite large gaps were allowed between units which could be filled with light troops or artillery and the skirmish line was usually very dense, approximately three times as heavy as the French, in extended rather than open order with only up to six feet between pairs, so much so that it was frequently mistaken for the main line of formed troops and could nearly function as such.

The choice of ground was also a vital ingredient and here and, as is well known, Wellington invariably chose high ground, together with strong points if possible, concealing and protecting his troops where he could. Where this concealment was possible it had a threefold effect. It hid the British main line from the French who were, thus, unable to judge when to deploy their columns into line for the fire fight and assault, it concealed the advancing French from the British who were unable to dwell on the sight of columns moving ever closer, and it protected the British from the worst physical and psychological effects of artillery fire.

The British were, thus, protected from the intimidating prospect of being stuck with a French bayonet, whilst the latter were effectively ambushed when someone said "stand up Guards", or whatever. Add to this the effect of a volley of close range musketry, the most damaging physically and psychologically, and the dislocation of expectations was complete. The final, and possibly most important, ingredient was a local British counter attack which decided the issue. It was a morale victory as much as anything else brought about by surprise. This combination, as we have seen, could be equally effective when the roles were reversed.

Discounting anomalous situations such as during sieges, there are numerous examples of British manoeuvre columns but I have not a shred of evidence to suggest that they were ever used without the intention of deploying.

That is not to say that none exists, of course, simply that I do not know of any. Since this entire article was motivated by the discussion of British columns, it would seem appropriate to examine some further examples. Sgt Robertson of the 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) Regiment mentions manoeuvre columns in his diary during the Egyptian campaign in 1801, but no detailed description of them is given.

As an aside, however, Robertson does describe how his and another battalion were deployed in extended order to act as light troops, there being none available, and how that extended line was able to develop sufficient musketry to beat off cavalry. Not only does this illustrate the density of a British skirmish line, but it should give pause for thought to those who claim that only light companies of British line battalions could deploy in that role.

A column of files would have been two wide, the sub-unit simply having made a left or right turn and marched off. The subsequent column appears to have been formed on platoon frontage and it is possible to infer that this was a result of ground. Batty does not specify open or closed columns.

Batty also describes an action later near Bayonne in which the 1st Division advanced "by battalions in columns of companies, the Brigades at deployment distances from each other". This sounds very similar to Pakenham's arrangement of the 3rd Division at Salamanca. No contact was made with the enemy but the spacing of Brigades at deploying distances indicates that the possibility was thought to exist. It is obvious from Batty's description that the intention was to deploy had contact been made.

Batty frequently alludes to columns but the type is not always described. He describes the crossing of the Nivelle thus, however, "allied columns descending from the fortified position in files to the banks of the river, and then forming columns in the most perfect order ... the ford was wide enough to cross by platoons".

The well known description by Costello supports the tactical use of lines, rather than column, for the assault in the British service.

A battalion at Vitoria, which he identifies as the 88th Regiment, although this is not relevant to the discussion, advanced under artillery fire to attack a French regiment deployed in line on the "verge" of a hill. The 88th was formed "in close column of companies" initially, and then "deployed into line, advancing all the time towards their opponents". The French line then fired a volley at them when they were "within 300 to 400 yards" sufficient to cause casualties because the 88th "closed their files on the gap it had made", and commenced to advance at "double time until within 50 yards nearer to the enemy", when they fired a volley in return before the French had time to fire a second volley, cheered and charged with the bayonet, the enemy breaking before impact. The close column of companies is clear enough and, exactly as manoeuvre columns were supposed to do, it deploys into line as soon as it comes under effective fire. It does not appear that the 88th had any intention of attacking the French in column. The range at which musketry was exchanged is interesting, 300 to 400 yards for the French, 250 to 350 yards ("50 yards nearer", not at 50 yards as this is often interpreted ) for the British. Rather longer ranges than we would normally consider to be useful I think.

British infantry regulations were unremarkable and anachronistic compared with those of their later peers. Doctrine, as it evolved in The Peninsula, undoubtedly emphasised the tactical defensive, if only for reasons of economy but which, again, is in stark contrast the that of the French and Napoleonic practise generally. British tactics differed in the density of the skir-mish line and the two rank deployment of the formed line, which of all the major powers, although well known generally, was used habitually only in the British service, and by Prussian fusilier battalions.

The way the British went about their business was unique during the period and borrowed little, if anything, from the French.

More Columns

-

Basics, Drill, Tactics, Doctrine, and Practice

Regulations and Tactics: Britain

Regulations and Tactics: France

Regulations and Tactics: Prussia

Regulations and Tactics: Austria

Regulations and Tactics: Russia

Corrections and Errata: Letter to Editor (FE18)

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #16

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com