After the near disaster at Chippawa, Riall decided to withdraw his forces to the north to Fort George and to the west to locations near Twelve- and subsequently Twenty-Mile creeks. Riall’s defeat and withdrawal from Chippawa ceded the initiative to Brown who moved north to Queenston, on the heights overwatching the lower Niagara River valley, and Forts George and Mississauga below him. Brown waited here for word from Sacketts Harbor and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commander of the naval force on Lake Ontario, to determine when he could expect reinforcements and the support of the heavy naval guns, guns he believed he needed to invest the forts.

After the near disaster at Chippawa, Riall decided to withdraw his forces to the north to Fort George and to the west to locations near Twelve- and subsequently Twenty-Mile creeks. Riall’s defeat and withdrawal from Chippawa ceded the initiative to Brown who moved north to Queenston, on the heights overwatching the lower Niagara River valley, and Forts George and Mississauga below him. Brown waited here for word from Sacketts Harbor and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commander of the naval force on Lake Ontario, to determine when he could expect reinforcements and the support of the heavy naval guns, guns he believed he needed to invest the forts.

Brown waited for two weeks in and around Queenston and the immediate area around Fort George. Some of Brown’s subordinates wanted to force the issue and attack the fort without the heavy guns, others wanted to pursue Riall’s forces in the west, only a day’s march away. Brown made some attempts to draw Riall’s forces to him and join in battle. Riall had Drummond’s permission to sit at Twenty-Mile creek and play a waiting game. Brown remained insistent that he would wait for word of naval support, and through his inaction allowed the British Right Division to once again gain the initiative, gather reinforcements, and deploy them to the Niagara peninsula (under Drummond’s direct leadership). When word finally did come from the fleet at Sacketts Harbor (dated 20 July) it was a reply in the negative, and that no naval support would be forthcoming in the near term. Brown decided to move back to Chippawa, unable to get the necessary support to attack the forts, and unable to make Riall come out and fight him at Queenston.

Riall managed to keep well informed of American troop movements through Pearson’s forces, some of who had stayed behind to screen and perform reconnaissance. Riall used this information to justify his plan of action to Drummond, a plan that can be simply described as doing nothing. Even when Brown’s forces withdrew from Queenston Heights back to Chippawa, Riall decided not to pursue and instead wait for Drummond’s reinforcements. Riall’s inaction meant the British no longer had the initiative in the campaign (neither side did at this point), and as Brown’s forces withdrew, the reconnaissance forces failed to maintain a steady contact, so Riall subsequently lost his ability to visualize the enemy situation, and therefore the operational picture. Both forces were blind as to the other’s dispositions and intentions, and neither side possessed the necessary initiative to successfully pursue their campaign objectives. There was momentary stalemate.

The stalemate did not last long, as the British again seized the initiative upon the arrival of General Drummond to York (Toronto) on 22 July. Riall was concerned that Brown’s forces had withdrawn so abruptly from Queenston, and sent Pearson’s forces out to reconnoiter and determine the enemy’s dispositions. This Pearson did, establishing his force at Queenston on 25 July, and sending scouting parties out to the south towards Chippawa, just four miles distant. At the same time, Drummond was readying forces to move to Niagara, and planned on sending some forces onto the U.S. side of the river, this due to reports that the Americans were constructing batteries opposite Fort George (a report that turned out to be false). Later in the day, Pearson received reports back from his scouts that there were American pickets located north of Chippawa. The scouts were not able to determine the disposition of the main body forces, though Pearson correctly surmised that they were encamped at Chippawa. Drummond and his forces would arrive by boat on the 25th, and the stage was now set for final movements to battle.

The U.S. forces were busy on the 25th too, as they had detected British movement in the vicinity of Queenston. Brown discounted reports from two of his trusted subordinate commanders, Majors Henry Leavenworth and Jesup, that the British appeared to be readying for a new offensive. It was at about this time that Brown also received reports from Youngstown that British naval forces had been spotted landing soldiers on the U.S. shore. Brown weighed the apparently conflicting information. He chose to believe that the British were attempting to interdict his supply line on the American side, and that the force immediately to his north was likely a ruse. This unintentional British deception worked because it fit with what Brown believed to be the greatest threat to his force, and because he trusted the source of the report (Lieutenant Colonel Philetus Swift of the New York Volunteers, the two having served together previously in the militia). Brown may have placed more credence on this report than on the word of two of his regimental commanders, perhaps due to the fact that as General Scott’s subordinates, Brown felt their loyalties remained with Scott.

Brown decided that the only way to prevent the British from a deep penetration of the Right Division’s rear was by a renewed offensive north towards Queenston and beyond. For this action he enlisted Scott’s brigade again, instructing Scott to find the enemy and request assistance if needed. Scott had been chaffing for action, and this order was all he needed, translating the directive into a command “to find the enemy and to beat him.”

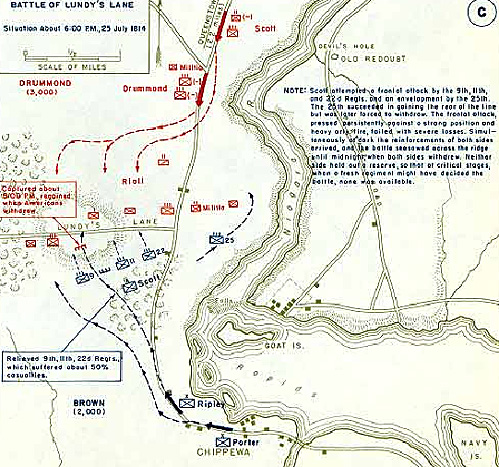

Scott launched his brigade almost immediately, failing to adequately scout out in front of his main body, and running into Riall’s lines (Pearson’s men) in the vicinity of Lundy’s Lane, an area of open high ground just south of Queenston. Riall had failed to detect Scott’s movement too, and once Scott’s force was spotted in the woods less than 600 meters away, Riall became concerned that he was outnumbered, as he assumed he was facing the entirety of the U.S. Left Division.

Critical Decisions It was at this point that each leader made a series of critical decisions, each ultimately impacting the course of the battle. Riall, concerned for the safety of his force, ordered a withdrawal to Queenston, with Pearson to cover by fighting a rearguard action. Fortunately for the British, Drummond was just north of the position, and came across the lead elements of the withdrawing forces. He quickly countermanded the order, and sped his march to Lundy’s Lane, arriving just in time to organize a linear defense along the lane that would absorb Scott’s initial assaults.

Scott’s brigade was in a tight spot. His rapid unscreened movement placed his lead elements within range of the British cannon once he moved out of the treeline at the bottom of the slope. Scott had to make a quick command decision, attack up the hill, or withdraw back to a position of safety and await Brown’s reinforcements. Already exposed, and never a person to shy from a fight (and the glory of Chippawa was still fresh in his memory), Scott sent word back to Brown to speed reinforcement, and rashly launched into an uphill frontal assault exposed, outnumbered, and at a marked disadvantage in terms of accurate artillery support.

Scott made one decision that ultimately would save a number of American lives and eventually help them carry the assault. He again sought out the trusted Major Jesup, and ordered him to move his regiment on a covered approach to the east along the left flank of the British line and “be governed by circumstances.” Jesup would successfully maneuver his force along the eastern edge of the battle area, and would inflict a number of punishing volleys into the British flank, causing it to fall back in on itself, and directing attention away from the action along the front. Jesup would also capture a number of British soldiers, including, most famously, a severely wounded Major General Riall.

Meanwhile, on the British right flank, Pearson’s mix of light forces had successfully fought a number of delaying actions that slowed Scott’s advance and allowing Drummond to strengthen the British line. Pearson’s forces would continue these efforts throughout the six-hour long battle, maintaining a strong, secure right flank, and allowing Drummond to concentrate on a weakened center and a threatened left flank.

Brown did not wait for Scott’s message to initiate movement. At the first sound of concerted firing Brown started both Ripley’s and Porter’s brigades moving north. Brown charged ahead to assist Scott as necessary. Brown arrived during a pause in the battle, and observed firsthand the tired state of Scott’s brigade. Ripley’s brigade arrived at about this time and Brown made a decision to seize the British guns positioned in the center of their line, believing them to be a decisive to the battle.

It was now past 9:00 pm as Ripley’s brigade assaulted up the hill, assisted by a renewed flank assault by Jesup (the timing of which was coincidental, there was poor coordination of the three brigade efforts throughout the battle--and campaign--one of General Brown’s key failings). Colonel Miller’s 21st Regiment succeeded in overwhelming the British center and taking the guns. This attack succeeded in great part due to a combination of the dark night and the increasingly confused battlefield. Brown and Ripley reinforced this local success and the British fell back, with the Americans now holding the high ground along the lane.

The final phase of the battle now commenced as Drummond determinedly led a series of counterattacks to retake the lane and the guns. This phase was the most confused, and mainly involved close in hand to hand fighting. The British made three separate assaults on the American line, the last ending around midnight. None of these assaults was successful in knocking the U.S. forces from the position, but these last determined actions were successful in exhausting both sides, and wounding a number of key leaders from both sides, including Brown, Scott (seriously), and Drummond.

As Brown was evacuated from the field, he passed command to Brigadier General Ripley, and told him to collect up the troops, the wounded, and the British cannon and return to Chippawa. For reasons that today still elicit great debate, Ripley failed to remove the captured cannon, and did not withdraw to Chippawa, instead moving all the way back (eventually) to Fort Erie. However, this controversy is outside the scope of this study. For the purposes of this paper, it is enough to know that the Americans left the field of battle to the British, left them their guns, and withdrew without being pursued by British forces that outnumbered them. It appeared to be a tactical draw, but a strategic defeat for the U.S. forces.

Battle Command and Initiative Leadership During the Battles of Chippawa and Lundy's Lane

- Introduction and Campaign Overview

Key Personalities

Battle of Chippawa

Battle of Lundy's Lane

Relevancy for Today / Conclusion

Orders of Battle (as of 25 July 1814)

Jumbo Map of Campaign Area (very slow: 305K)

Bibliography

Back to Table of Contents -- War of 1812 #4

Back to War of 1812 List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Rich Barbuto.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com