The third U.S. invasion of Canada commenced early in the morning of 3 July 1814, as Winfield Scott led his brigade across the Niagara River from Black Rock (now a northern section of Buffalo) towards Fort Erie. The plan, as determined by Secretary Armstrong and General Brown, was to take Fort Erie, and then march north towards Chippawa and Fort George--to be “governed by circumstances.” The first phase of the campaign proceeded smoothly as the small garrison at Fort Erie, keenly aware that they were substantially outnumbered and outgunned, surrendered the same day with barely a fight.

The third U.S. invasion of Canada commenced early in the morning of 3 July 1814, as Winfield Scott led his brigade across the Niagara River from Black Rock (now a northern section of Buffalo) towards Fort Erie. The plan, as determined by Secretary Armstrong and General Brown, was to take Fort Erie, and then march north towards Chippawa and Fort George--to be “governed by circumstances.” The first phase of the campaign proceeded smoothly as the small garrison at Fort Erie, keenly aware that they were substantially outnumbered and outgunned, surrendered the same day with barely a fight.

Messages were immediately sent back to Chippawa, and then to Major General Riall at Fort George, that American forces had landed near Fort Erie. Riall immediately initiated the movement of the Royal Scots to reinforce Chippawa, and wait there for the likely American advance. The position at Chippawa was well suited to the defense, situated behind an unfordable river that had but one bridge across it. Riall was in no hurry to go on the offensive, as he believed that the garrison at Fort Erie would hold out and buy him some time to gather his forces. He sent out a guard force of light infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Pearson to maintain contact with the advancing Americans and delay their movement northward.

On 4 July, as Pearson’s forces were moving south, Brown was directing Scott to begin moving north to seize a crossing of the Chippawa. Yet again the order from senior to subordinate was to be “governed by circumstances,” as apparently this provided the subordinate the greatest latitude while affording the senior commander a degree of defense should the operation go awry. For the entire day of the fourth, Scott’s brigade would be determinedly delayed by Pearson’s light forces, which destroyed bridges all along the sixteen-mile route northward to the Chippawa. This delaying action successfully slowed Scott’s advance, but could not stop it as his forces reached the area between Street’s Creek and the Chippawa River before nightfall. Scott reconnoitered Riall’s position behind the Chippawa and correctly determined that he did not have the force capable for an assault. With this, Brown’s forces withdrew for the night behind Street’s Creek, less than a mile and a half south of Riall.

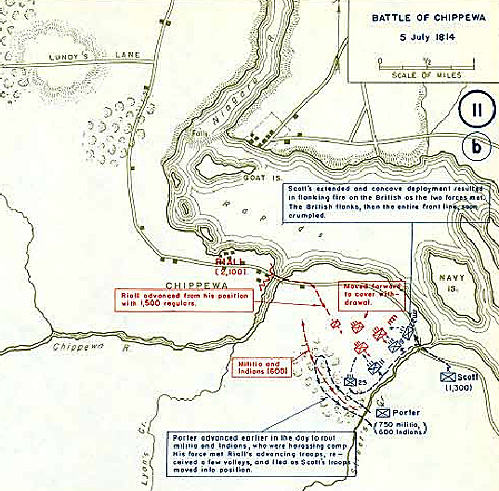

The morning 5 July opened with Brown ordering elements of Brigadier General Peter B. Porter’s New York militia brigade forward into the woods to the northwest and clear it of Pearson’s snipers and skirmishers. This was not a part of the planned offensive, but simply Brown’s solution to rid the camp of the disturbing interruptions. At the same time, Riall decided to come out from his stronghold and assault the forces he knew were just south of his position. Riall sent a strong force of natives and militia into the western woods to screen his movement, while at the same time lining up his forces on the Chippawa bridge to prepare for the advance. Riall’s motives for moving from a position of strength have been questioned, but he believed that he was stronger in numbers, had a more capable fighting force, and was not yet aware that Fort Erie has fallen so easily. He did not know he would potentially face all of Brown’s division.

As the day grew later battle was joined. Porter’s forces made a strong advance north through the woods, driving back the light militia and natives. Just as they reached the line south of the Chippawa they were driven back by determined fire from infantry regiments readying for the assault. Riall had already moved his advance elements south of the bridge on the open plain between the two armies. Brown rode forward to investigate and “realized from the cloud of dust rising and the heavy firing that the whole force of the enemy was in march and prepared for action.” He then ordered the adjutant, Colonel Gardner to ride back with order for Scott “to form his brigade…and advance to ‘meet the enemy’.”

Scott, upon receiving the orders relayed by Gardner, did not believe that the situation was so dire, but that Porter’s militia had got in a fight and that Scott now had to back them up. He readied his brigade, half preparing for a fight and half preparing for the parade that he had previously decided to conduct to keep the men focused. Just as Scott’s lead forces were crossing the bridge over Street’s Creek, General Brown rushed by on horseback and shouted to Scott, “You will have a battle!” Scott was not sure what to make of his commander’s state, unaware that Brown was rushing back to warn Brigadier General Eleazar W. Ripley to ready the Second Brigade for a fight. However, Scott quickly realized the seriousness of the situation as he crossed the bridge and saw Riall’s forces forming in the open plain to his front.

Scott made a quick decision to form for battle, as a retreat back across the creek was not an option. He believed this was the opportunity to prove his brigade’s training fitness in battle. While Scott maneuvered his forces across the bridge and out into the open, Riall’s field guns began firing. Scott’s brigade held steady and formed as per their drills in the line of this increasing fire. This surprised Riall who, when seeing Scott’s force come across the bridge in their grey uniforms, believed them to be the same New York Militia he had so soundly defeated the year prior. When they didn’t break and run under the heavy fire, instead continually reforming their lines, Riall is suspected to have uttered these now famous words, “Why, these are regulars!”

The fight was now joined as the two lines faced one another, with their supporting artillery alternating between counterbattery and antipersonnel fire missions. Scott split his forces so that he could cover more frontage and match the more numerous British line, with McNeill’s 11th Infantry Regiment on the left, and the 9th and 22nd Regiments combined under Leavenworth on the right. Once again the mission to “be governed by circumstances” was issued, this time by Scott as he ordered Jesup to cover the left flank and the woodline. Facing Scott was the 1st Foot on the British Right, with the 100th Foot on the left. To the right rear was the 8th Foot.

The battle was short and violent, and marked the first time these two country’s armies had met on an open plain in traditional linear battle. The timely and skillful maneuvering of Scott’s brigade would win the day. Riall’s soldiers did not expect the U.S. soldiers to withstand more than one or two volleys, and became somewhat dismayed when the Americans not only stood their ground, but also advanced. The independent actions of Major Jesup’s 25th Regiment played a key role in the Left Division’s success. He conducted a series of maneuvers that secured the flank from the British and Canadian militia positioned in the woods. Subsequently he wheeled his formation around at a crucial moment to fire into the flank of the British right, inflicting a high number of casualties. The U.S. artillery had also won their counterfire duel, and they were now free to fire into the British left flank. Riall managed to withdraw his forces safely back across the Chippawa, fighting all the way under withering fire. The U.S. Army had achieved a resounding tactical victory, Scott’s training regimen had proven its worth, and the subordinate commanders of First Brigade had all distinguished themselves in their exercise of courage, command presence, and initiative. The one key U.S. failing was that the battle was only a brigade fight, with Brown unable to get the brigades of Ripley and Porter into the battle in time to effect what may have been a strategic (decisive) victory.

Battle Command and Initiative Leadership During the Battles of Chippawa and Lundy's Lane

- Introduction and Campaign Overview

Key Personalities

Battle of Chippawa

Battle of Lundy's Lane

Relevancy for Today / Conclusion

Orders of Battle (as of 25 July 1814)

Jumbo Map of Campaign Area (very slow: 305K)

Bibliography

Back to Table of Contents -- War of 1812 #4

Back to War of 1812 List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Rich Barbuto.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com