From Zanana to the Barike River

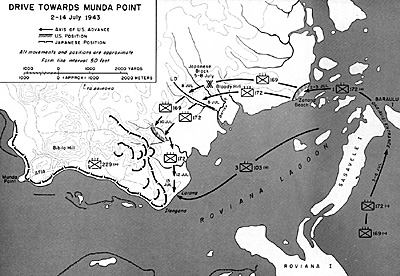

Once the 169th and 172d Regiments had landed at Zanana, General Hester had originally planned, the two regiments were to march overland about two and one-half to three miles to a line of departure lying generally along the Barike River, then deploy and attack west to capture Munda airfield. (Map 9)

Drive Towards Munda Point

Drive Towards Munda Point

Jumbo Map: Drive Towards Munda Point (Extremely slow: 289K)

The regiments were directed to reach the line of departure and attack by 7 July, but by the time the two regiments had reached Zanana all operations were postponed one day.

The overland approach to Munda involved a march through the rough, jungled, swampy ground typical of New Georgia. The terrain between Zanana and Munda was rugged, tangled, and patternless. Rocky hills thrust upward from two to three hundred feet above sea level, with valleys, draws, and stream beds in between. The hills and ridges sprawled and bent in all directions. The map used for the operation was a photomap based on air photography. It showed the coast line and Munda airfield clearly, but did not give any accurate indication of ground contour. About all the troops could tell by looking at it was that the ground was covered by jungle.

The difficulty of travel in this rough country was greatly increased by heat, mud, undergrowth, and hills. Visibility was limited to a few yards. There were no roads, but a short distance north of Zanana lay Munda Trail, a narrow foot track that hit the coast at Lambeti Plantation. Engineers were making ready to build a road from Zanana to Munda Trail, and to improve the latter so that it could carry motor traffic.

Having made their way from Zanana to the line of departure on the Barike, the two regiments would, according to Hester's orders, deliver a co-ordmated attack against Munda airfield, which lay about two and one-half miles westward. The 172d Infantry on the left (south) would be responsible for a front extending inland from the coast. The 169th Infantry's zone of action lay north of the 172d's; its right flank would be in the air except for protection given it by South Pacific Scout patrols operating to the north. The attack would be supported by General Barker's artillery and by air and naval bombardments.

Two days after the beginning of the two- regiment attack, a heavy naval bombardment would prepare the way for an assault landing by the 3d Battalion, 103d Infantry, and the 9th Marine Defense Battalion's Tank Platoon at 0420, 9 July, at the west tip of Munda Point.

Hester and Wing did not expect to meet any serious opposition between Zanana and the Barike River, and their expectations must have been confirmed by the experience of the ist Battalion, 172d. On 3 July Colonel Ross had ordered this battalion to remain at Zanana, making every effort at concealment. The message was apparently not received, for on 4 July the battalion, accompanied by A Company, 169th Infantry, easily marched to the Barike River, meeting only small Japanese patrols on the way. It was this premature move that helped to alert Sasaki.

Next morning Captain Sherrer of the G-2 Section led a patrol of six New Zealanders, twelve Americans, and eighteen Fijians from his base camp toward the upper reaches of the Barike River. They intended to set up a patrol base on high ground suitable for good radio transmission and reception.

Normally they would have avoided detection by moving off the trails and striking out through the wilderness, but, laden with radio gear, they followed Munda Trail. As they approached a small rise that lay about two miles from Zanana, and about eleven hundred yards east of the line of departure, they met enemy machine gun fire. They replied with small arms, and the fire fight lasted until dusk when Sherrer's group disengaged and went south to the bivouac of the 1st Battalion, 172d, near the mouth of the Barike.

B Company, 172d, went out to investigate the situation the next morning and found the Japanese still occupying the high ground, astride the trail. Attacks by B Company and by A Company, 169th, failed to dislodge the Japanese. By afternoon of 6 July, however, the three battalions of the 172d Infantry were safely in place on the Barike, the 1st and 3d on the left and right, the 2d in regimental reserve.

But the 169th Infantry, commanded by Col. John D. Eason, was not so fortunate. That regiment's 3d Battalion, under Lt. Col. William A. Stebbins, set out along the trail from Zanana to the line of departure on the morning of 6 July. Natives guided the battalion as it moved in column of companies, each company in column of platoons, along the narrow trail. The men hacked vines and undergrowth to make their way more easily. Shortly after noon, General Wing ordered Stebbins' battalion to destroy the point of Japanese resistance that Sherrer had run into.

It was estimated, correctly, that about one platoon was trying to block the trail. General Sasaki, aware of the Allied activity east of him, had ordered part of the 11th Company, 229th Infantry, to reconnoiter the Barike area, clear fire lanes, and establish this trail block with felled trees and barbed wire.

The 3d Battalion, 169th, apparently did not run into the block on 6 July. It dug in for the night somewhere east of the block, but does not seem to have established the sort of perimeter defense that was necessary in fighting the Japanese in the jungle. Foxholes were more than six feet apart. The battalion laid no barbed wire or trip wire with hanging tin cans that rattled when struck by a man's foot or leg and warned of the approach of the enemy.

Thus, when darkness fell and the Japanese began their night harassing tactics-- moving around, shouting, and occasionally firing--the imaginations of the tired and inexperienced American soldiers began to work. They thought the Japanese were all around them, infiltrating their perimeter with ease. One soldier reported that Japanese troops approached I Company, calling, in English, the code names of the companies of the 3d Battalion, such stereotypes as "come out and fight," and references to the Louisiana maneuvers. (169th Inf Hist, 20 Jun-30 Sep 43, p. 5.)

The men of the battalion, which had landed in the Russells the previous March, must have been familiar with the sights and sounds of a jungle night, but affected by weariness and the presence of the enemy, they apparently forgot. In their minds, the phosphorescence of rotten logs became Japanese signals. The smell of the jungle became poison gas; some men reported that the Japanese were using a gas which when inhaled caused men to jump up in their foxholes. The slithering of the many land crabs was interpreted as the sound of approaching Japanese.

Men of the 169th are reported to have told each other that Japanese nocturnal raiders wore long black robes, and that some came with hooks and ropes to drag Americans from their foxholes. In consequence the men of the battalion spent their nights nervously and sleeplessly, and apparently violated orders by shooting indiscriminately at imaginary targets.

Next day, the shaken 3d Battalion advanced with I Company leading followed by L, M, Battalion Headquarters, and K Companies. It ran into machine gun fire from the Japanese trail block at 1055. I Company deployed astride Munda Trail, L Company maneuvered to the left, K was initially in reserve. M Company brought up its 81-mm. mortars and heavy machine guns but could not use them profitably at first as banyan trees and undergrowth blocked shells and bullets. The mortar platoon then began clearing fields of fire by cutting down trees. B Company of the 172d also attacked the block from the south.

I Company launched a series of frontal assaults but was beaten back by machine gun fire. Three platoon leaders were wounded in these attacks. K Company came out of reserve to deliver a frontal assault; its commander was soon killed. Neither it nor any of the other companies made progress.

The Japanese were well dug in and camouflaged. Riflemen covered the automatic weapons. Fire lanes had been cut. The enemy weapons had little if any muzzle blast, and the Americans had trouble seeing targets. Some tried to grenade the enemy but were driven back before they could get close enough to throw accurately. At length the 81-mm. mortars got into action; observers operating thirty yards from the Japanese position brought down fire on it. Some Japanese are reported to have evacuated "Bloody Hill," as the Americans called it, that afternoon. At 1550 the 3d Battalion withdrew to dig in for the night. (The 169th Infantry History (P. 4) claims that the block was destroyed on 7 July, and that a day was lost when the 1st Battalion, 169th, moved ahead of the 3d on 8 July. But messages in the 43d Division G-3 journal indicate that the block was still active on 8 July.)

After dark the Japanese harassed the 3d Battalion again. According to the 169th Infantry, "a sleepless night was spent by all under continued harassing from enemy patrols speaking English, making horror noises, firing weapons, throwing hand grenades, swinging machetes and jumping into foxholes with knives." (169th Inf Hist, P. 4.)

On 8 July, the 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, which had been behind the 3d within supporting distance, was ordered to bypass the 3d and move to the Barike while the 3d Battalion reduced the block. On 7 July General Wing had ordered Colonel Ross to use part of the 172d against the block, but apparently by the afternoon of 8 July no elements of the 172d except B Company had gone into action against it.

On 8 July the 3d Battalion, 169th, and B Company, 172d, struck the block after a mortar preparation and overran it. The 3d Battalion lost six men killed and thirty wounded, and suffered one case diagnosed as war neurosis, in reducing the block. The trail from Zanana to the Barike was open again, but the attack against Munda had been delayed by another full day.

By late afternoon of 8 July, the 1st Battalion, 169th, had reached the Barike River and made contact on its left with the 3d Battalion, 172d; A Company, 169th, had been returned to its parent regiment; the 3d Battalion, 169th, was behind and to the right of the ist Battalion. With the two regiments on the line of departure, Hester and Wing were ready to start the attack toward Munda early on 9 July. Hester told Wing: "I wish you success." ( 43d Div G-3 Jul, 8 Jul 43.)

The Approach to the Main Defenses

By 7 July General Hester, after conferences with General Wing and Colonels Ross and Eason, had abandoned the idea of the amphibious assault against Munda by the 3d Battalion, 103d Infantry, and the 9th Marine Defense Battalion's tank platoon. He was probably influenced in his decision by the strength of the Munda shore defenses.

The plan for the attack on 9 July called for the 169th and 172d Regiments to advance from the Barike, seize the high ground southwest of the river, and capture the airfield. On the high ground, a complex of ridges that ran from Ilangana on the beach inland in a northwesterly direction for about three thousand yards-were the main Japanese defenses.

TROOPS OF THE 172D INFANTRY WADING ACROSS A CREEK on the Munda Trail.

TROOPS OF THE 172D INFANTRY WADING ACROSS A CREEK on the Munda Trail.

The 172d Infantry was to move out astride the Munda Trail with the 1st and 3d Battalions abreast. Each battalion zone would be three hundred yards wide. Battalions would advance in column of companies; each rifle company would put two platoons in line. The 169th Infantry, maintaining contact on its left with the 3d Battalion, 172d, would advance echeloned to the right rear to protect the divisional right flank. The 1st Battalion was to advance abreast of the 172d; the 3d Battalion would move to the right and rear of the 1st.

The regimental commanders planned to advance by 200-yard bounds. After each bound, they intended to halt for five minutes, establish contact, and move out again. They hoped to gain from one to two thousand yards before 1600.

The division reserve consisted of the 2d Battalion, 169th, which was to advance behind the assault units. Antitank companies from the two regiments, plus Marine antiaircraft artillerymen, were defending the Zanana beachhead. In Occupation Force reserve, under Hester, was the 3d Battalion, 103d Infantry, on Rendova. H Hour for the attack was set for 0630

General Barker's artillery on the offshore islands inaugurated the first major attack against Munda at 0500 of 9 July with a preparation directed against rear areas, lines of communication, and suspected bivouac areas and command posts. After thirty minutes, fire was shifted to suspected centers of resistance near the line of departure.

In one hour the 105-mm. howitzers of the 103d and 169th Field Artillery Battalions, the 155-mm. howitzers of the 136th Field Artillery Battalion, and the 155-mm. guns of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion fired over 5,800 rounds of high explosive. Starting at 0512, four destroyers from Admiral Merrill's task force, standing offshore in the Solomon Sea, opened fire at the area in the immediate vicinity of the airfield in accordance with plans prepared in consultation with General Barker. Naval authorities had originally wanted to fire at targets close to the line of departure as well, but the 43d Division, fearing that the direction of fire (northeast to east) might bring shells down on its own troops, rejected the proposal. (Merrill thought the 43d Division was generally too cautious. See Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 179.)

Between 0512 and 0608, the destroyers fired 2,344 5-inch rounds. At 0608, four minutes before the bombardment was scheduled to end, some Japanese planes dropped bombs and strafed one ship; the destroyers retired.

Then Allied planes from Guadalcanal and the Russells took over. Fifty-two torpedo bombers and thirty-six dive bombers dropped seventy tons of high explosive bombs and fragmentation clusters on Munda. Now it was the infantry's turn.

H Hour, 0630, came and went, but not a great deal happened. The 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, reported that it was ready to move but could not understand why the 172d Infantry had not advanced. At 0930, General Wing was informed that no unit had yet crossed the line of departure.

Several factors seem to have caused the delay. Movement as usual was an ordeal. The Barike was flooded. Soldiers, weighted with weapons, ammunition, and packs, had to wade through waist-to-shoulder-deep water.

The river, which had several tributaries, wound and twisted to the sea. It crossed the Munda Trail three times; the spaces between were swampy. The men, sweating in the humid heat, struggled to keep their footing, and pulled their way along by grabbing at roots and undergrowth. Leading platoons had to cut the wrist-thick rattan vines.

Although patrols of New Georgians, Fijians, Tongans, New Zealanders, and Americans had reconnoitered the area, their information could not always be put to good use. There was no accurate map on which to record data, nor were there any known landmarks.

In the jungle, orthodox skirmish lines proved impractical. As men dispersed they could not be seen and their leaders lost control. At any rate, movement off the trails was so difficult that most units moved in columns of files, the whole unit bound to one trail. Thus one or two Japanese, by firing on the leading elements, could halt an entire battalion.

The Occupation Force intelligence officer had estimated that the main Japanese defenses lay 1,600 yards from the Barike, anchored on Roviana Lagoon and extending inland to the northwest. This was correct, except that the defense line on the ridges was actually about 2,500 yards from the Barike's mouth. Beyond the main defenses, the Japanese outposts, using rifles, machine guns, and sometimes mortars and grenade dischargers, were well able to delay the advance.

At 1030 General Barker returned to the 43d Division command post from a tour of the front and reported that at 1000 the 172d Infantry was a hundred yards beyond the Barike, but that the 169th was still east of the river. The only opposition had come from the outpost riflemen that the Americans usually called "snipers." At the time these were believed, probably erroneously, to be operating in the treetops. (Whereas the Japanese, like the Allies, used trees whenever possible for observation posts, it is doubtful that "snipers" used many trees in the jungle. See Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, p.318. Anyone who has ever climbed a tree in the jungle can testify to the difficulties a man with a rifle would encounter--lack of visibility, tree limbs in the way, and the innumerable little red ants whose bite is like the prick of needles.)

Japanese fighter aircraft appeared over New Georgia during the day; the Allied air power prevented any from getting close enough to strafe the attacking troops.

By 1630, when it dug in for the night, the 172d had gained some eleven hundred yards. (From 1100, 8 July, to 1300 9 July, this regiment was commanded by Lt. Col. Charles W. Capron. Colonel Ross, wounded on 30 June, had apparently been ordered to Rendova for medical treatment.)

The 169th had made no progress to speak of. The 1st Battalion got one hundred yards west of the Barike; the other two apparently remained east of the river.

The 169th was facing about the same obstacles as the 172d, but it is possible that the 169th was a badly shaken regiment before the attack began. (The 172d was either not subjected to night harassing or was not sufficiently bothered by it to report it.)

The night before the attack, 8-9 July, the 3d Battalion was bivouacked near Bloody Hill, and the other two lay to the west. When the Japanese made their presence known to the three battalions, or when the Americans thought there were Japanese within their bivouacs, there was a great deal of confusion, shooting, and stabbing. Some men knifed each other. Men threw grenades blindly in the dark. Some of the grenades hit trees, bounced back, and exploded among the Americans. Some soldiers fired round after round to little avail. In the morning no trace remained of Japanese dead or wounded. But there were American casualties; some had been stabbed to death, some wounded by knives. Many suffered grenade fragment wounds, and 50 percent of these were caused by fragments from American grenades. These were the men who had been harassed by Japanese nocturnal tactics on the two preceding nights, and there now appeared the first large number of cases diagnosed as neuroses. The regiment was to suffer seven hundred by 31 July.

The 43d Division resumed the attack on 10 July. The 172d Infantry, reporting only light opposition, advanced a considerable distance. The 169th Infantry, with the 1st Battalion in the lead and the 2d Battalion to its right rear, advanced successfully until it reached the point where the Munda Trail was intersected by a trail which ran southeast to the beach, then circled to the southwest to the native villages of Laiana and Ilangana. Reaching this junction about 1330 after crossing a small creek on two felled tree trunks, the leading battalion was halted by machine gun fire. This fire came from rising ground dominating the trail junction, where Capt. Bunzo Kojima, commanding the 9th Company, 229th Infantry, had established a camouflaged trail block. He employed one rifle platoon, reinforced by a machine gun section, some 90-mm. mortars, and elements of a 75-mm. mountain artillery battalion.

When the 1st Battalion was stopped, Colonel Eason decided to blast the strong point. While the infantry pulled back a hundred yards, the 169th's mortars and the Occupation Force artillery opened fire. Barker's guns fired over four thousand rounds of 105-mm. and 155-mm. high explosive, shattering trees, stripping the vegetation, and digging craters. (One fortunate concomitant of artillery fire was better visibility as the heavy shellings tore the jungle apart.)

Coincident with this bombardment, eighty-six Allied bombers (SBD's and TBF's) unloaded sixty-seven tons of bombs on Lambeti Plantation and Munda. During the artillery bombardment Kojima's men lay quiet but when the fire ceased they immediately stood to their guns and halted the American infantrymen when they attacked. At the day's end, the Japanese were still on the high ground; the 169th Infantry, after advancing about fifteen hundred yards, was forced to bivouac in a low swampy area. The American commanders concluded that they were nearing a main defensive line. They were right. The high ground to their front contained the main Japanese defenses that were to resist them for weeks.

Laiana Beachhead

By 11 July, the advancing regiments were still in trouble. Progress had been slowed by the enemy, and also by the supply problems arising from the fact that the troops had landed five miles east of their objective and thus committed themselves to a long march through heavy jungle. Now the regiments, in spite of their slow advance, had outdistanced their overextended supply line.

The 118th Engineer Battalion had made good progress in building a jeep trail from Zanana to the Barike River. Using data obtained from native scouts, the engineers had built their trail over high, dry ground, averaging one half to three quarters of a mile per day. There was little need for corduroying with logs, a time-consuming process. When they ran into trees too big to knock down with their light D-3 bulldozers, the engineers blasted them with dynamite.

Lacking heavy road-graders, the 118th could not make a two-lane, amply ditched road, but it managed to clear a one-lane track widened at regular intervals to permit two-way traffic. Near a five-foot-deep, fast-running stream east of the Barike the engineers hit soft mud. To get to ground firm enough to permit construction of footbridges and two thirty-foot trestle bridges, they were forced to swing the road northward parallel to the river for two and one-half miles to get to a firm crossing.

The advancing regiments crossed the Barike on 9 July, but several days were to elapse before the bridges were completed.

Thus there was a gap between the end of the road and the front. To bridge the gap, nearly half the combat troops were required to carry forward ammunition, food, water, and other supplies, and to evacuate casualties. Allied cargo planes were used to parachute supplies to the infantry, but there were never enough planes to keep the troops properly supplied.

With fighting strength reduced by the necessity for hand carry, with his right flank virtually exposed, and his extended supply line open to harassment by the enemy, Hester decided, on io July, to change his plan of attack in order to shorten the supply line. If a new beachhead could be established at Laiana (a native village about two miles east by south from Munda airfield), some five thousand yards would be cut off the supply line.

Patrols, operating overland and in canoes, examined Laiana beach at night and reported that it was narrow but suitable, with a coral base under the sand. Unfavorable aspects included a mangrove swamp back of the beach and the fact that the Japanese main defenses appeared to start at Ilangana, only five hundred yards southwest of Laiana, and arch northwest toward the Munda Trail.

JEEP TRAIL FROM ZANANA, built through heavy jungle by 118th Engineer

Battalion, 13 July 1943.

JEEP TRAIL FROM ZANANA, built through heavy jungle by 118th Engineer

Battalion, 13 July 1943.

But the advantages outweighed the disadvantages. Hester ordered the 172d Infantry to swing southward to Laiana, seize and hold a beachhead from the land side, then advance on Munda. The 169th Infantry was to continue its attempt to drive along the Munda Trail. Hester ordered the reinforced 3d Battalion, 103d Infantry, at Rendova, to be prepared to land at Laiana after the 172d had arrived.

At 1000, 11 July, the 172d Infantry disengaged from the attack, turned south, and started moving toward shore through knee-deep mud. The regiment tried to keep its move a secret, but Japanese patrols quickly observed it, and mortar fire soon began hitting it. The wounded were carried along with the regiment. The advance was halted about midafternoon after a gain of some 450 yards. Both 1st and 3d Battalions (the 2d had remained behind to block the trail and thus cover the rear until the 169th could come up) reported running into pillboxes. Aside from the mortar shelling and some infiltration by patrols between the 172d and the 169th, the Japanese appeared to have stayed fairly still.

The march was resumed on 12 July with the hope of reaching Laiana before dark, for the regiment had not received any supplies for two days. Colonel Ross reported that the carrying parties equaled the strength of three and onehalf rifle companies. Despite this fact, and although food and water were exhausted, the regiment kept moving until late afternoon when leading elements were within five hundred yards of Laiana. There machine gun and mortar fire halted the advance.

At this time scouts confirmed the existence of pillboxes, connected by trenches, extending northwest from Ilangana. The pillboxes, which the Americans feared might be made of concrete, housed heavy machine guns, and were supported by light machine guns and mortars.

That night (12-13 July) Japanese mortars registered on the 172d's bivouac, and the troops could hear the Japanese felling trees, presumably to clear fields of fire.

His hungry, thirsty regiment was without a line of communications, and Colonel Ross, concerned over the Japanese patrols in his rear, had to get to Laiana on 13 July. With the artillery putting fire ahead, the 172d started out through mangrove swamp on the last five hundred yards to Laiana. The enemy fire continued. The advance was slow, but late afternoon found the 172d in possession of Laiana.

LCM's APPROACHING LAIANA, New Georgia, under Japanese artillery fire, 14 July

1943. The Tank Platoon of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion is aboard these landing craft.

LCM's APPROACHING LAIANA, New Georgia, under Japanese artillery fire, 14 July

1943. The Tank Platoon of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion is aboard these landing craft.

It organized the area for defense while patrols sought out the Japanese line to the west. That night twelve landing craft left Rendova to carry food and water to Laiana and evacuate the wounded. For some reason the 172d failed to display any signals. The landing craft, unable to find the right beach, returned to Rendova.

When the 172d was nearing Laiana on 13 July, General Hester ordered the 3d Battalion, 103d Infantry, 43d Division, to be prepared to land at ogoo the following morning. The Tank Platoon of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion was attached; to help the tanks and to aid in the reduction of fixed positions, engineers (bridge builders, demolitions men, flame thrower operators, and mine detector men) were also attached.

The reinforced battalion, loaded in LCP(R)'s and LCM's, rendezvoused at daybreak of 14 July in Blanche Channel. When the daily fighter cover arrived from the Russells, the landing craft started for Laiana. With the 172d already holding the beachhead, the first wave landed peacefully at 0900. Reefs forced some craft to ground in waist-deep water, but the hungry soldiers of the 172d helped unload them. As the LCM's neared shore Japanese artillery shells began falling on the water route and on the landing beach.

To blind the Japanese observers, the field artillery fired more than five hundred white phosphorous rounds as well as high explosive at suspected Japanese gun positions and observation posts on Munda Point and on the high ground (Bibilo Hill) northeast of Munda field. The Japanese artillery did no damage.

General Sasaki reported that he had repulsed the landing, and that the Americans had lost, of seventy landing craft, thirteen sunk and twenty damaged. Nevertheless, 8th Area Army headquarters appears to have learned that the landing had succeeded.

Once ashore, 43d Division engineers began building a jeep trail from Laiana north to the 169th Infantry. Supplies came in for the 172d, and its wounded men were evacuated. Telephone crews laid an underwater cable between Zanana, Laiana, and General Barker's artillery fire direction center.

The 3d Battalion, 103d, was still in division reserve, but Colonel Ross was authorized to use it in case of dire need. He committed L Company to fill a gap between the 2d and 3d Battalions of the 172d on the morning of 15 July when the 172d was making an unsuccessful attack toward Ilangana. Soldiers of the Antitank Platoon of the 3d Battalion, 103d, disassembled a 37-mm- gun, carried it forward, reassembled it on the front line, and destroyed three pillboxes with direct fire. This was the only success; the day's end found the 172d still facing the main enemy defense line.

The Seizure of Reincke Ridge

While the 172d had been driving to Laiana and getting ready to attack westward, the 169th Infantry was pushing against the high ground to the north. On 10 July, the day before the 172d turned southward, the 169th had been halted. It faced Japanese positions on the high ground which dominated the MundaLambeti trail junction. The Munda Trail at this point led up to a draw, with hills to the north (right) and south (left). The Japanese held the draw and the hills.

The regiment renewed the attack on 11 July just before General Hester replaced Colonel Eason with Col. Temple G. Holland, but made no gains. When Holland took over the regiment, he ordered the advance postponed until the next morning. The exact nature of the Japanese defenses was not yet completely clear, but it was evident that the Japanese had built mutually supporting pillboxes on the hills.

Holland's plan for 12 July called for the 1st Battalion to deliver the attack from its present position while the 2d Battalion enveloped the Japanese left (north) flank .21 The 3d Battalion, temporarily in division reserve, would be released to the regiment when the trail junction was secure. The 169th attacked as ordered but bogged down at once, partly because it became intermingled with elements of the 172d, which was starting for Laiana. When the units were disentangled the two battalions attacked again. The 1st Battalion ran head on into Japanese opposition but reported a gain of three hundred yards. The 2d Battalion received enfilading fire from the northernmost ridge but kept its position. (Ltr, Col Holland to Gen Smith, Chief of Mil Hist, 12 Oct 53, no sub, OCMH.)

A second attack, supported by a rolling barrage, was attempted in the afternoon. The infantry, unable to keep pace with the barrage which moved forward at the rate of ten yards a minute, fell behind and halted. At the day's end, Holland, who reported to Hester that his regiment was badly disorganized, asked General Mulcahy for air support the following day.

Next morning, 13 July, after thirty minutes of artillery fire and a twelve-plane dive-bombing attack against the south ridge, the 169th attacked again. All three battalions were committed. The 2d Battalion, in the center, was to assault frontally up the draw while the ist Battalion, on the right, and the 3d Battalion on the left, moved against the north and south ridges with orders to envelop the Japanese.

The 3d Battalion, with I and L Companies in line and M in support, struggled forward for four hours. (K Company had been detached to guard the regimental command post.)

It pushed four hundred to five hundred yards into theJapanese lines and managed to secure its objective, the south ridge, which it named Reincke Ridge for Lt. Col. Frederick D. Reincke, who had replaced Stebbins in command on 8 July.

The other two battalions were not as successful. The 2d Battalion, with E and F Companies in line and G in support, met machine gun fire in the draw, halted, was hit by what it believed to be American artillery fire, and pulled back. The 1st Battalion, attacking the north ridge, found it obstructed by fallen limbs from blasted trees and by shell and bomb craters. The Japanese who had survived the bombardments opened fire from their pillboxes and halted the assaulting companies. The battalion, now operating without artillery or mortar support, tried to assault with rifle and bayonet. Some men started to climb to the ridge crest but were killed or wounded by machine gun fire. B Company lost three of its four officers in the attempt. Japanese artillery and mortar fire cut communication to the rear. The battalion returned to its original position.

The st and 2d Battalions took positions on the flanks and rear of the 3d Battalion, which held Reincke Ridge. The Japanese held the north ridge and the draw. To the west they held the higher ground called Horseshoe Hill. To the south was the gap left by the 172d when it turned south.

In spite of the 3d Battalion's exposed situation Holland and Reincke decided to hold the hardwon position which was the only high ground the 169th possessed. Its possession was obviously vital to the success of an attack against the main enemy defenses.

All that night and all the next day (14 July) the Japanese tried to push the 3d Battalion from Reincke Ridge. I Company was hit hard but held its ground with the loss of two men killed and nineteen wounded. Artillery and mortar shells kept exploding on the ridge top, while Japanese machine guns covered the supply route to the rear. During its first twenty-four hours on the ridge, Reincke's battalion suffered 101 casualties; L Company consisted of just fifty-one enlisted men by the end of 14 July During part of the time no medical officer was present, but the battalion medical section under S/Sgt. Louis Gullitti carried on its duties of first aid and evacuation.

On the same day Holland reorganized the other two battalions. The regimental Antitank Company had landed at Zanana on 13 July and been assigned the task of carrying supplies forward from the trail's end. This task had eased, because the engineers finished bridging the Barike on 12 July and by 14 July had extended the trail to within five hundred yards of the 169th's front lines. Rations, water, and ammunition were parachuted to the regiment on 14 July. Colonel Holland relieved part of the Antitank Company of its supply duties and assigned sixty of its men to the 2d Battalion, twenty to the 1st. He also sent patrols south to cover the gap to his left. Late in the afternoon he reported to Hester that morale in his regiment had improved.

Next day the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, landed at Zanana and was immediately attached to the 43d Division with orders to advance west and relieve part of the 169th on the line. The battalion reached the regiment at 1700. Colonel Holland put it in regimental reserve pending the completion of the operations against the hills in front of him.

Operations against Munda airfield had gone very slowly but by 15 July had achieved some success. Liversedge had captured Enogal and while waiting for another battalion was getting ready to attack Bairoko. The 169th Infantry had some high ground and was in contact with the main enemy defense line. The 172d Infantry was also in contact with the main Japanese defenses, and the new beachhead at Laiana would soon shorten the supply line.

More The Offensive Stalls

- Japanese Plans

Operations of Northern Landing Group

Operations of Southern Landing Group

Casualties

Command and Re-inforcements

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com