The March to Dragons Peninsula

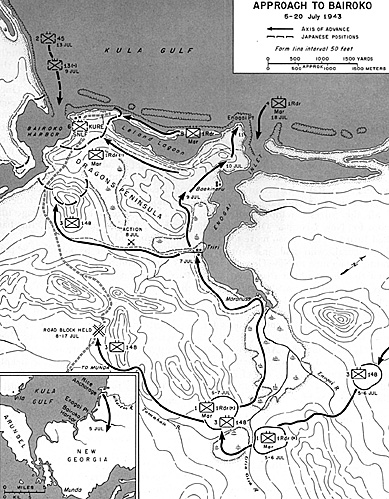

At 0600 Of 5 July, with nearly all his Northern Landing Group ashore and in hand, Colonel Liversedge ordered his troops to move out. The 1st Marine Raider Battalion, the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry, and K and L Companies of the 145th Infantry were to advance southward toward Dragons Peninsula, the piece of land lying between Enogai Inlet and Bairoko Harbour. (Map 8) Once they had reached the head of Enogai Inlet, the Raiders and K and I Companies, 145th, were to swing right to take the west shore of Enogai Inlet prior to assaulting Bairoko, while the 3d Battalion, 148th, advanced southwest to block the Munda-Bairoko trail. M, L, and Headquarters Companies of the 3d Battalion, 145th Infantry, were ordered to stay and defend Rice Anchorage under Lt. Col. George C. Freer, the battalion commander.

The preinvasion reconnaissance parties, after examining the ground between Rice Anchorage and Dragons Peninsula to determine whether an overland attack would be practicable, had reported the country generally level with sparse undergrowth. There were no swamps.

Enogai Inlet, with a good anchorage, had a mangrove-covered shore line except at its head where firm ground rose steeply to an elevation of about five hundred feet. Dragons Peninsula itself was hilly, swampy, and jungled, but on the inland shore of Leland Lagoon a ridge ran from Enogai to Bairoko village. Bairoko Harbour was deep, and was backed by swamplands.

Approach to Bairoko Across Dragons Peninsula

Approach to Bairoko Across Dragons Peninsula

Jumbo Map: Approach to Bairoko (Extremely slow: 321K)

The advance to Dragons Peninsula began immediately after Liversedge issued his orders. Guided by natives, the troops moved along the three parallel trailsthe original track and the two cut by Corrigan's natives. The 1st Marine Raider Battalion, Lt. Col. Samuel B. Griffith, III, commanding, led the way, followed in order by K and L Companies, 145th, under Mal. Marvin D. Girardeau, and Lt. Col. Delbert E. Schultz's 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry.

The patrols' reports had implied that the going would be easy, but the march proved difficult. The rough trails, winding over hills and ridges, were obstructed by branches, roots, and coral outcroppings. Ram wet the troops all day.

The Raiders, whose heaviest weapon was the 60-mm. mortar, made fairly steady progress, but the soldiers of M Company, 148th Infantry, fell behind as they floundered through the mud with their heavy machine guns, 81-mm. mortars, and ammunition.

At 1300 part of D Company of the Raiders, the advance guard, was sent on ahead to secure a bridgehead on the far bank of the Giza Giza river. (At this time the lettered companies of the 1st Raider Battalion were all rifle companies; there was no heavy weapons company.)

Three hours later the Raiders' main body and the companies of the 145th Infantry arrived at the river and bivouacked there overnight. They had covered five and one-half miles in the day's march without meeting a single Japanese. Colonel Schultz's battalion camped for the night about one and one-half miles to the north.

Next morning, 6 July, the Raiders led out again, and D Company pushed ahead to secure a crossing over the Tamakau River. The rains had flooded the river; it was now nine feet deep. Without tools or time to build a proper bridge, the Raiders threw a log over the stream, and improvised rafts from poles and ponchos to ferry over their heavy equipment. After several rafts had capsized, they gave up and carried everything over on the log. Several men slipped off the log and fell into the swollen river; a few had to be rescued from drowning. The crossing had started before noon, but not until dusk did the last man cross the river. Schultz's battalion, also delayed by high water, caught up with the Raiders and bivouacked near them for the night.

On the morning Of 7 July the Raiders and Girardeau's companies set out for Enogai, while Schultz's battalion pushed south toward the Munda-Bairoko trail. The country was rough, the going hard for both forces. The Raiders took five hours to cover the 2,500 yards between their bivouac and the east end of Enogai Inlet.

The 3d Battalion, 148th, reached the trail at 1700. In the afternoon the two hundred men who had been landed astray on 5 July caught tip with the main body. There had been no opposition from the Japanese; a patrol was observed but kept its distance.

Capture of Enogai Inlet

When the Marine Raiders and Girardeau's two companies reached Enogai Inlet, one platoon, again from D Company, pushed forward to secure the deserted village called Maranusa. From there a patrol marched toward Triril another village which was hardly more than a clearing. Up to now the marines had not seen any Japanese, but as the patrol approached Triri its point detected five Japanese ahead. The marines ambushed the party and killed two of its members. They belonged to the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force. The other three fled. When Liversedge heard about this action, which made it obvious that his force had been discovered, he ordered Griffith to secure Triri at once in order to prepare to repel a counterattack. Griffith dispatched the demolition platoon from battalion Headquarters Company with orders to pass through D Company and seize Triri.

On the way up, the platoon ran into a strong enemy patrol which opened fire. The marines retired to a defensive position on the bank of a stream and kept the enemy in place with fire. At this point D Company appeared on the scene, swung to the left, struck the Japanese on their inland (right) flank, and drove them off. Three marines and ten Japanese were killed in this skirmish. One of the dead Japanese had on his person a defense plan which showed the exact location of the heavy guns at Enogai. By 1600 all elements of the Enogai attacking force were installed at Triri.

At dawn the following morning--8 July, the day on --which Schultz's battalion completed its block on the Munda-Bairoko trail-two Raider combat patrols went out of Triri. B Company sent one out to ambush a trail which led northwesterly to Enogai, and a D Company patrol advanced south along a cross-country track leading to Bairoko to lay another ambush. This patrol had advanced a short distance by 0700, when it ran into an enemy force of about company strength. A fire fight broke out, and at looo Griffith sent C Company to drive the enemy back a short distance.

In the meantime, the patrol which had advanced toward Enogai reported no contact with the enemy. In order to assemble all companies of the 1st Raider Battalion for the attack against Enogai, Griffith sent K and L Companies of the 145th south to take over from C Company. C Company then disengaged, moved back to Triri, and in the early afternoon the 1st Raider Battalion marched northwest toward Enogai. But the trail led the marines into an impassable mangrove swamp. The battalion therefore retired to Triri, while scouts hunted for a better route to use the next day.

In the south sector, the fight between the Japanese and K and L Companies had continued. The Japanese in repeated assaults struck hard at K Company which was on the right (west). Capt. Donald W. Fouse, commanding K Company, was wounded early in the action but stayed with his company until the fight was over. When the Raider battalion retired to Triri, the Demolition Platoon was committed to the line, and when K Company was hard hit a platoon from B Company of the Raiders swung wide around the Japanese left flank and struck them in the rear. This maneuver succeeded. The enemy scattered. (K Company reported killing a hundred Japanese; the marine platoon is reported to have killed twenty.)

The 1st Raider Battalion resumed its advance against Enogai the next morning, using a good trail, apparently unknown to the Japanese, that led over high ground west of the swamp. K and L Companies remained to hold Triri, the site of Liversedge's command post. Griffith's battalion, meeting no opposition, made good time. By 1100, the Marines were in sight of Leland Lagoon. They swung slightly to the right toward Enogai Point and at 1500 ran into two Japanese light machine guns which opened fire and halted the advance. Griffith deployed, with A Company on the left, C in the center, B on the right, and D in reserve. The companies then assaulted, but the Japanese defended so resolutely that no further progress was made that day.

Patrols reconnoitered vigorously so that by 0700, 10 July, Griffith had been informed that the Japanese were strongest in front of his center and left, and that there were no Japanese directly in front of B Company. The battalion resumed the attack at 0700. C and A Companies advanced slowly against rifle and machine gun fire. Supported by 60 mm. mortars, B Company drove forward rapidly, cleared the village of Baekineru, and captured two machine guns. Then A Company, strengthened by one platoon from battalion reserve, pushed over Enogai Point to the sea.

By 1500 all organized resistance had ended except for a pocket in front of A Company. When D Company started establishing beach defenses, it was troubled by three machine guns from another enemy pocket. Mopping up these two groups of Japanese took until 11 July.

The Raiders had run out of food and water by midafternoon of io July, but were succored by L Company, 145th, which brought rations and water up from Triri. These had been dropped, at Liversedge's urgent request, by C- 47's from Guadalcanal.

By 12 July Enogai was organized for defense against land or seaborne attacks. Estimates of Japanese casualties ranged from 150 to 350. Postwar Japanese accounts assert that Enogai was defended by one platoon of soldiers and 81 men of the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force. The marines lost 47 killed, 4 missing, and 74 wounded. They captured three .50-caliber antiaircraft machine guns, 4 heavy and 14 light machine guns, a searchlight, rifles, mortars, ammunition, 2 tractors, some stores and documents, and the 4 140-mm. coastal guns that had harassed the landing at Rice Anchorage. The guns were intact except that their breechblocks had been removed. Luckily, a marine digging a foxhole uncovered one, and a hasty search of the area turned up the other three. The marines used these guns to help guard the seaward approaches to the newly won position. (Sasaki apparently had ordered two of these guns to Munda.)

Roadblock North of Munda

While the Raiders were thus engaged, the soldiers of the 3d Battalion, 148th Infantry, were deep in the jungle holding their block. The block, completed on 8 July, was set up on a well-used trail some two miles southeast of Enogai Inlet and eight miles north of Munda. I Company, with one M Company platoon attached, faced toward Bairoko; K Company faced Munda. L Company covered the flanks of I and K, and extended its lines back to protect the battalion command post. M Company, with the Antitank Platoon attached, was in a supporting position to the rear. Each rifle company field one platoon in reserve under battalion control. All positions were camouflaged.

Colonel Schultz ordered his men to fire at enemy groups larger than four men; smaller parties were to be killed with bayonets.

The battalion held the block from 8 through 17 July. Patrols went out regularly. General Hester had ordered patrols to push far enough to the south to make contact with the 43d Division's right flank as it advanced westward against Munda, but this was never done.

Schultz was strengthened on 11 July by the addition of I Company, 145th Infantry, after a group of Japanese had overrun part of L Company's positions in a series of attacks starting io July. Except for this, the Japanese made no effort to dislodge Schultz's men, whose greatest enemy proved to be hunger. The troops had left Rice Anchorage carrying rations for three days on the assumption that Enogai Inlet would be taken in two days and that American vessels could then land stores there. These could be delivered to the troops after a relatively short overland haul. But Enogai was not secured until 11 July. The 120 native carriers thus had to carry food all the way from Rice Anchorage. Although, according to Colonel Liversedge, the natives "accomplished an almost superhuman task," they could not carry supplies fast enough to keep the troops fed. (1st Mar Raider Regt [NLG], Combat Rpt and War Diary, 4 Jul-29 Aug 43 entries.)

By 9 July the food shortage was serious. Only 2,200 D rations had been delivered. Late that evening, with food for the next day reduced to one ninth of a D and one ninth of a K ration per man, Schultz radioed to Liversedge an urgent request that food be brought in by carrier. He also hoped the natives could carry out two badly wounded men who were being cared for in the battalion aid station. But as there were not enough natives, C-47's dropped food, as well as ammunition, to the battalion the next afternoon.

Much of the food fell far beyond the 3d Battalion's lines, and some of the ammunition was defective. Schultz was forced to cut the food allowance for the next twenty-four hours to one twelfth of a K ration. Fortunately Enogai had now fallen, and on 13 July Flight Officer Corrigan's natives carried in three hundred pounds of rice which the men cooked in their helmets, using salt tablets for seasoning. The next day, though, was another hungry one; one D and one K ration was the allowance for each eighteen men. Thereafter, until the block was abandoned, carrying parties and air drops kept food stocks high enough.

During the nine days it held the block, the 3d Battalion lost 11 men killed and 29 wounded; it estimated it had killed 250 Japanese.

At the time it was believed that the blockers had cut off Munda from reinforcement via Bairoko, and that they held the Japanese Bairoko force in place, prevented Enogai from being reinforced from either Munda or Bairoko, and protected Griffith's right flank and rear. (NGOF, Report of Operations on New Georgia; 1st Mar Raider Regt, Special Action Rpt, New Georgia, 6 Oct 43.)

Knowledge gained after the event indicates that none of these beliefs was warranted.

That Munda was not isolated is demonstrated by the fact that the Japanese reinforcement of Munda was in full swing, and all the reinforcements seem to have reached Munda without much trouble. The enemy obviously stopped using the blocked trail after 8 July and shifted to another one farther west.

Meanwhile, reinforcement by water continued. On 9 July, when 1,200 Japanese from the Shortlands landed on Kolombangara, 1,300 of the 13th Infantry transferred by barge to Bairoko. Three days later, on 12 July, a Japanese tenship force left Rabaul to carry 1,200 more soldiers to Kolombangara, and Halsey sent Ainsworth's task force to intercept again. The two forces collided early on 13 July northeast of Kolombangara in a battle named for that island. The Allies lost the destroyer Gwin; the New Zealand light cruiser Lcandcr and the American light cruisers St. Louis and Honolulu suffered damage. The Japanese flagship, the light cruiser Jintsu, was sunk, but 1,200 enemy soldiers were landed on the west coast of Kolombangara. (For a full account of the battle see Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 180-81.)

At Bairoko, during this period, the 13th Infantry made ready to go to Munda. It was part of this regiment which attacked the trail block on io July. (An enemy account claims that the Americans were "annihilated." See 17th Army Operations, Vol. II Japanese Monogr NO. 40 (OCMH).)

On 13 July, when the Bairoko garrison was strengthened by the 2d Battalion, 45th Infantry, and a battery of artillery, the 13th Infantry marched south to the Munda front.

As far as pinning down the Bairoko troops was concerned, the block lay more than two miles from Bairoko, and thus could not have affected the Bairoko garrison very much. And surely, had the Japanese desired to reinforce Enogai from Bairoko, they would have used the direct trail along the shore of Leland Lagoon rather than going over the more roundabout route which was blocked.

In view of the American strength at Rendova and Zanana, the thesis that the Japanese might have sent troops from Munda to Enogai is equally untenable, even if it were not known that the Japanese were reinforcing Munda, not Enogai. Finally, Schultz's battalion was too far from Griffith's to render much flank protection in that dense, dark jungle. (On 10 July General Hester explicitly directed Colonel Liversedge to keep his battalions within supporting distance of one another.)

It is clear that the trail block failed to achieve results proportionate to the effort expended. So far, the principal effect of the entire Rice Anchorage-Enogai-Bairoko operation had been to employ troops that could have been better used at Munda.

By 11 July, with Enogai secured, Liversedge was five days behind schedule. Casualties, illness, and physical exhaustion had reduced the 1st Raider Battalion to one-half its effective strength. Considering that two fresh battalions could reduce Bairoko in three days, he asked Admiral Turner, with Hester's approval, for additional troops. There were not two more battalions to be had, Turner replied, but he promised to land the 4th Raider Battalion at Enogai by 18 July, and authorized a delay in the assault against Bairoko until then. Thus short one battalion, Liversedge directed Schultz to abandon his block and march to Triri on 17 July. The 3d Battalion, 148th, was to join the Raiders and part of the 3d Battalion, 145th, in the Bairoko attack.

The Northern Landing Group had accomplished the first phase of its mission by capturing Enogai, but was behind schedule. On the Munda front, General Wing's Southern Landing Group was also behind schedule.

More The Offensive Stalls

- Japanese Plans

Operations of Northern Landing Group

Operations of Southern Landing Group

Casualties

Command and Re-inforcements

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com