Peltast Equipment

Peltast Equipment

In many ways, a foot soldier in Classical Greece was defined by his shield. The hoplite carried a large, heavy round shield (aspis), and thus they were the `heavily armed.' This made the hoplite slow and cumbersome.

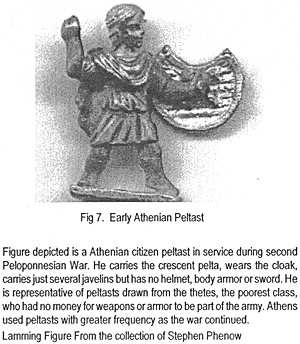

Fig 7. Early Athenian Peltast

Figure depicted is a Athenian citizen peltast in service during seconc Peloponnesian War. He carries the crescent pelta, wears the cloak carries just several javelins but has no helmet, body armor or sword. HE is representative of peltasts drawn from the thetes, the poorest class who had no money forweapons or armor to be part of the army. Athen: used peltasts with greater frequency as the war continued. Lamming Figure From the collection of Stephen Phenow.

[This seems a good place to point out that contrary to popular belief a hoplite is NOT named after his shield. A cursory glance at Thucydides and Xenophon in the original Greek will reveal that the shield a hoplite carried was called an aspis. The word aspis in reference to a hoplite's shield occurs 50 times in Xenophon and over 10 times in Thucydides' Peloponnesian War. 'Hoplon' is not used at all for shield. Hoplites means `heavy armed', and this refers both to the large and heavy shield as well as a heavy bronze cuirass, greaves, helmet, and sometimes additional arm and leg armour, which were used by the early type of hoplite.

As the hoplite evolved, lightening his load (then later coming full circle back to muscle cuirasses), he retained the aspis. This was a heavy piece of equipment, weighing about 15 lbs. 'Hoplite' in fact comes from an old verb hoplizo, meaning to prepare, to arm; and the noun hoplon is generally a tool or piece of heavy equipment, later as arms and armour generally - compare the Greek and English word `pan-OPLY(IA),' meaning `all-equipment'. Note that when Diodorus says the hoplite (heavily armed) was named after his shield, he means that he is named after the fact that his shield is much heavier than that of other troops].

The psiloi generally carried no shield (though he often wrapped a cloak or animal hide around his left arm (See Fig. 4). The peltast carried a small shield, often of the Thracian crescent shape. It is sometimes depicted as a circle, not much smaller than an aspis, with a small piece cut out, but more usually it is a true crescent. Completely round small shields are also shown, and later oblong ones appear. This small shield afforded the peltast some protection against both missiles and melee weapons, though clearly not as much as an aspis - peltast shields seem to have been made out of wicker covered with leather or hide and so besides being smaller, they were also much less resistant than the heavy wood and bronze aspis. [Though see above for the bronze-faced pelte carried by Cretan archers]. Such shields often had an attached strap so they could be slung on one's back to allow freer movement, especially in retreat, where it might also afford some protection to one's back: "Then the Thracians took to flight, swinging their shields around behind them, as was their custom."[An. 7.4.17] (See Fig 5.)

The most common armament of the peltast, in both art and literature, is one or more javelins (although, as we have seen, this was far from always the case). These often had a thong attached, increasing its range: "the javeliners with hand on the thong and the bowmen with arrow on the string" [An. 4.3.28. See the attic black-figure cup at National Museum, Copenhagen, for a clear depiction]. (See Fig 6.)

It seems clear that if and when peltasts ran out of javelins they used any stones they could find. [See for example, Hell, 2.4.33, Hell. 4.6.7, Hell. 5.1.10]. In art, if a side arm is carried, it is usually a dagger or short sword, though non-Hellenic peltasts can carry small axes and clubs too. As we have seen, a 'peltast' may also be an archer or slinger - if acting as either of these, it is unlikely that he carried his pelta, though Cretan archers and Rhodian slingers are known to have sometimes carried shields.

Armor was usually not worn, though helmets and cuirasses do occasionally appear; usually light composite varieties - perhaps hemithorakions ('half-cuirasses'). For example, an archer in the Nereid Monument wears a cuirass. Thracians, Amazons, Anatolians and others with peltas carry weapons suitable to their people, whether spears, bows or axes. This later changed. (See Fig. 7.)

Function in War

During the Classical period, warfare changed radically at the level of campaign, though battles themselves were fought in much the same way, with much the same troops.

The northern Hellenic cities in Thrace, and the Macedonians and Thessalians - as well as parts of Central and Western Greece - had a history of using peltasts. But for the first half of our period they were not used in the Greek cities of the South (south of and including Thebes, also Athens, Megara, Corinth and the whole Peloponnese) though colonists from the South no doubt encountered peltasts in Thrace and elsewhere. Southern states such as Athens and Sparta did use peltasts when campaigning in areas where peltasts were to be found - as for example Brasidas and Cleon in and around Amphipolis and the Chalkidike - but the first mention ofpeltasts being used in the South is in the force that Cleon took to Pylos in 425 where some Spartans were besieged by the Athenians on the island of Sphakteria; Thucydides mentions an undefined number of peltasts from Aenus, a Hellenic city in Thrace, accompanying this force.[P. W. 4.28].

The next mention of peltasts is the 500 fighting for the Thebans in 427 at Delium - quite possibly also Thracian mercenaries .[PW, 4 This is another example of the military innovativeness of Thebes, even at this stage - apart from this first use ofpeltasts, see for example the use of cavalry long before other Southern Hellenic states, their use of cavalry flank manoeuvre at Delium, the use of hammipoi (light infantry trained to fight with the cavalry), the Sacred Band as epilektoi (professional hoplites) before these troops were used by other poleis, and the use of deep hoplite formations already as early as 423].

The first mention of Southern Hellenic peltasts are the 5,000 trireme rowers Thrasyllus the Athenian strategos equipped as peltasts in 409.[Hell. 1.2.1] This is a very large number indeed, but it seems clear that this measure was taken due to the low cost of equipping - and no doubt paying at this time - peltasts compared to hoplites. These would have been chiefly the poorest of Athenians, the thetes. These made up the majority of his force, which operated in the eastern Aegean - the rest being made up of 1,000 hoplites and 100 cavalry from Athens. This was the first instance of the trend for using large numbers of peltasts on campaign, sometimes completely unsupported by other troops, which was a chief feature of the warfare of 4" century Classical Greece.

Ten years after Thrasyllus' innovation, we hear of Dracon, an Achaean fighting for the Spartan strategos Dercylidas, commanding a force of 3,000 mercenary peltasts, which operated as an autonomous force in Ionia - some years before Iphikrates' more famous mercenary peltasts. [Isocrates, Panegyrics 144. Isocrates also tells us that Timotheus the Athenian besieged and took Samos with 8,000 peltasts and 30 triremes. Isoc. Antidosis 111 ]. These seem to have been local Greeks, and were used for raiding the surrounding area in a kind of guerrilla warfare.

By far the most famous mercenary peltast force is that of Iphikrates the Athenian. These were highly successful both on campaign and in actual fighting. As they became veterans of war, they were able to fight effectively at times against hoplites, with support from friendly heavy troops. Their most famous exploit was the defeat of the Spartan mora at Lechaeum in 390. However, it must be pointed out that there were only 600 Spartan hoplites, that they and the cavalry were incompetently led, and that they only broke when the large force of Athenian hoplites bore down on them after suffering many casualties from the peltasts. Still, this incident clearly shows what well-led peltasts could do, in the right circumstances, to even the best trained hoplites.

The question that naturally arises is, why did the Greeks begin to rely more and more on the peltast. As already mentioned, one factor, at least at the beginning of the change, would have been the relatively low cost of such troops compared to hoplites and cavalry.

But there was more to it than that. At the start of the Classical Era, wars were decided largely by set-piece battles, involving a clash of each side's hoplites in a grand melee, while other troops (usually present in very small numbers) did little to affect the result of the battle. This began to change with the constant and intense warfare of the Peloponnesian War, a trend which only increased into the next century. This new warfare required smaller forces that could be absent for longer periods; it required greater strategic flexibility, with raiding, sieges and fighting in terrain other than carefully selected flat plains the norm.

By the 370s, a new warfare was being waged. The passes that often formed the only entrance into a state's land suitable for armies were now guarded against the enemy - usually by peltasts, due to their ability to fight in difficult terrain and their missile ability. Indeed if such passes were contested, it was usually to the peltast that the task fell.

In 379 the Spartan king, Cleombrotus, invaded Thebes, but the road that led through Eleutherae was guarded by Chabrias and his Athenian peltasts. [Hell. 5.4.14]. Cleombrotus therefore went via a different rout; here too a pass was held, but he sent his peltasts ahead and these cleared the way for the rest of the army. [Hell. 5.4.14].

Here Xenophon describes how an entire invasion campaign with a large army could be halted by occupied passes:

- "The Lakedaimonians, however, when spring was just starting, again mobilized and directed Cleombrotus to take command. When he arrived at Mount Cithaeron with the army, his peltasts went on to occupy in advance the heights above the road. But some ofthe Thebans and Athenians who were already in possession of the summit allowed the peltasts to ascend for a time, and when they were close upon them rose from concealment, pursued them, and killed about forty. After this had happened, Cleombrotus, in the belief that it was impossible to cross over the mountain into the country ofThebes, led back and disbanded his army. "[Hell. 5.4.59].

The Spartan king here calls off the entire invasion due to a strategically placed small force. It was not always peltasts that occupied strategic heights however; Spartan hoplites, by far the most versatile, could do so, too. During Agesilaos of Sparta's invasion of Corinth, the king, "sent one regiment (`mora ', and thus clearly hoplites) up the heights to proceed along the topmost ridge. On that night, accordingly, he was in camp at the hot springs, while the regiment bivouacked, holding possession of the heights."[Hell. 4.5.3].

The Peltast in Classical Greece

-

Preface and Introduction

What is a Peltast?

Speed and Maneuverability

Equipment and Function

Effectiveness in Battle

Conclusion and Bibliography

Peltasts in Action Diagram (27K)

Peltasts on Attic Amphora (86K)

Peltasts on Attic Cup (73K)

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com