However he was armed and armored, the peltast's equipment was certainly lighter than that of the hoplite - even during the period of the hoplites' lightest panoply. At the start of the hoplite era, in the early Archaic period, the hoplite was very heavily armored indeed. Aside from his heavy aspis, helmet, spear and sword (the minimum equipment for a hoplite) he also wore a heavy cuirass and greaves of bronze, and sometimes arm, foot and leg protection.

However he was armed and armored, the peltast's equipment was certainly lighter than that of the hoplite - even during the period of the hoplites' lightest panoply. At the start of the hoplite era, in the early Archaic period, the hoplite was very heavily armored indeed. Aside from his heavy aspis, helmet, spear and sword (the minimum equipment for a hoplite) he also wore a heavy cuirass and greaves of bronze, and sometimes arm, foot and leg protection.

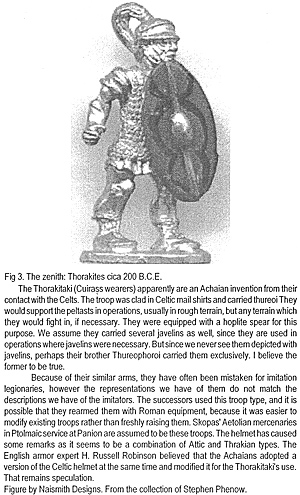

Fig 3. The zenith: Thorakites cica 200 B.C.E.

The Thorakitaki (Cuirass wearers) apparently are an Achaian invention from their contact with the Celts. The troop was clad in Celtic mail shirts and carried thureoi They would support the peltasts in operations, usually in rough terrain, but any terrain which they would fight in, if necessary. They were equipped with a hoplite spear for this purpose. We assume they carried several javelins as well, since they are used in operations where javelins were necessary. But since we neversee them depicted with javelins, perhaps their brother Thureophoroi carried them exclusively. I believe the former to be true.

Because of their similar arms, they have often been mistaken for imitation legionaries, however the representations we have of them do not match the descriptions we have of the imitators. The successors used this troop type, and it is possible that they rearmed them with Roman equipment, because it was easier to modify existing troops rather than freshly raising them. Skopas' Aetolian mercenaries in Ptolmaic service at Panion are assumed to be these troops. The helmet has caused some remarks as it seems to be a combination of Attic and Thrakian types. The English armor expert H. Russell Robinson believed that the Achaians adopted a version of the Celtic helmet at the same time and modified it for the Thorakitaki's use. That remains speculation. Figure by Naismith Designs. From the collection of Stephen Phenow.

By the time of the Persian Wars the cuirass was usually a composite of leather or linen and bronze, and the extra limb protection was dropped. By the end of the Peloponnesian War, helmets were lighter and cuirasses and greaves were often completely neglected; this trend continued into the 4th century. In the second third of that century, heavier helmets, greaves and muscle cuirasses of bronze are once again in use. Additionally, peltasts fought in looser formation, with more space around each individual soldier. Asklepiodotos tells us " the most open order in which men are both spaced in length and depth is four cubits (approx. 6 feet) is called no special name." These two factors gave him greater speed and maneuverability than the hoplite, and this was the peltast's chief defining feature.

This speed often defined where and how the peltast fought. Peltasts who were part of a balanced force usually fought in front of or on the flanks of the phalanx. Similarly, the way peltasts fought took advantage of their maneuverability, getting close to heavier-armed and thus slower enemies, showering him with missiles, and then retiring when the enemy approached them. Additionally, their speed made peltasts ideal for pursuing a defeated foe. Lastly, their loose formation made peltasts excellent troops for fighting in difficult terrain.

In the Van

There are many instances of peltasts positioned at the forefront of the army when fighting alongside hoplites, both before the battle for scouting purposes and gaining dominating terrain, and as the initial attacking force in the actual fighting.

Xenophon, for example, states his own use of peltasts as a scouting force during the march of the Ten Thousand [An. 4.5.20]. Also in the Anabasis, Xenophon says, "Meanwhile the main body of the Greeks was moving up from the plain, with the peltasts charging at a run upon the enemy's line, and Cheirisophus following double-time with the hoplites." [An. 4.6.25].

This rush at the enemy was sometimes made together with ekdromoi ('out-runners,' hoplites detailed to run out from the phalanx, often to deal with lightly equipped foes). Describing the tactics of the Spartan king, Agesilaos, Xenophon says, "Therefore, after sacrificing, he immediately led his phalanx against the enemy line of cavalry, ordering the first ten year-classes of hoplites to run to close quarters with the enemy, and telling the peltasts to lead the way at double-time."[Hell. 3.4.23].

On the Flanks

Peltasts were also often placed on the flanks of the army. The Spartans used this formation, as did the Ten Thousand: "When Dercylidas learned of all this, he told the commanders of divisions and the captains to form their men into line eight deep as quickly as possible, and to station the peltasts on either wing with the cavalry,"[Hell. 3.2.16] and, "After they had got the peltasts into position on either flank, they took up the march against the enemy."[An. 6.5. 25. See also, An .6.7.23: "The men acted as their own marshals, and within a short time the hoplites had fallen into line eight deep and the peltasts had got into position on either wing."].

Here Xenophon describes an instance reveals the reason for this deployment:

- "Now Cheirisophus, Xenophon, and the peltasts that were with them got past the wings of the enemy's line as they advanced. When the enemy saw this, they ran out of line, some to the right and others to the left, to engage them - with the result that their line was pulled apart and a large part of the center was left isolated. "[An. 4.8.16].

Being placed on the flanks or in the van was the usual place for peltasts, but there were exceptions. The Ten Thousand adopted a different formation when accompanied by allied Thracian peltasts: "And as soon as he had given over their guides to the Greeks, the hoplites took the lead, the peltasts followed, and the horsemen brought up the rear."[An. 7.3].

In Pursuit

The peltasts' speed made them excellent troops for pursuing the defeated foe. When fighting the Carduchi, themselves lightly-equipped, Xenophon describes one such instance: "Then Lycius; who commanded the Greek cavalry, and Aeschines, commander of the peltasts, upon seeing the enemy routed set off in pursuit, while the rest of the Greeks shouted to them not to fall behind, but to follow the enemy right up to the mountain."[An. 4.3.22]. Another instance of peltasts pursuing, this time accompanied by hoplites, occurred when the Ten Thousand were fighting the Mossynoeci - after routing the enemy with the aid of supporting hoplites: "The peltasts at once made after them and pursued them up the hill to the city, while the hoplites followed along, still keeping their lines."[An. 5.4.24].

Difficult Terrain

The peltasts' loose formation also made them excellent troops for occupying and fighting in difficult terrain - terrain which would disrupt a hoplite formation's cohesion, and be inappropriate for mounted troops. Xenophon reveals his thinking of the use of peltasts in the following passage from the Anabasis:

- `By the time it was midday he was already upon the heights, and catching sight of the villages below he came riding up to the hoplites and said: "Now l am going to let the horsemen charge down to the plain on the run, and to send the peltasts against the villages. You, then, follow as fast as you can, so if any resistance is offered, you may meet it. "[An. 7.3.44].

Once dominating difficult terrain was occupied, peltasts could harass the enemy with missiles while themselves remaining safe. Here is a passage in which a force of Acamanian peltasts forced Agesilaos and his men down from the hills they were occupying: "But now many Acarnanian peltasts came up, and, because Agesilaos was encamped on the mountain-side, by throwing stones and discharging slings from the ridge of the mountain they succeeded in forcing the army to descend to the plain, without suffering any harm themselves."[Hell. 4.6.7].

Ambushes

Ambushes

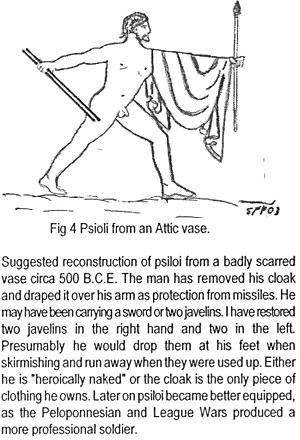

Fig 4 Psioli from an Attic vase.

Suggested reconstruction of psiloi from a badly scarred vase circa 500 B.C.E. The man has removed his cloak and draped it over his arm as protection from missiles. He may have been carrying a sword or two javelins. I have restored two javelins in the right hand and two in the left. Presumably he would drop them at his feet when skirmishing and runaway when they were used up. Either he is 'heroically naked" or the cloak is the only piece of clothing he owns. Later on psiloi became better equipped, as the Peloponnesian and League Wars produced a more professional soldier.

The peltasts' speed and maneuverability, combined with this ability to fight from and in difficult terrain, made them ideal ambushers. In 389 Iphikrates and around 1,200 peltasts were in the Chersonese to defend Athenian interests from the Spartans. There, Anaxibius, a Spartan general, was leading a force of 1,000 mercenaries and 200 hoplites, as well as a few Spartans.

- " [Iphikrates] crossed to the least inhabited part ofAbydene territory at night, went up into the mountains and set an ambush... Iphikrates did move from his hidden position so long as the army of Anaxibius was on level ground. But when the Abydenes, who were in thefront, were in the plain of Cremaste, where the gold mines are, and the rest of the army was following down the slope, and Anaxibius with his Lakedaimonians wasjust beginning the descent, at this moment Iphikrates started his men up from their ambush and rushed upon him at the double. "[Hell. 4.8.35].

The ambush was a resounding success: Anaxibius and the few Spartans stayed and died - the rest fled. Here again the peltasts revealed their ability to pursue successfully, killing 200 of the mercenaries and about 50 of the hoplites in the pursuit.

Later in the 380s, Chabrias the Athenian general took a force of 800 peltasts and a `force' of hoplites to the island of Aegina:

- "During the night, he and his peltasts landed in Aegina and set an ambush in a place beyond the Heracleium. At dawn, as was arranged, the Athenian hoplites marched inland. As soon as Gorgopas heard this, he marched out with theAeginetans and the marines, as well as eight Spartiates, as well as many rowers armed with whatever weapons they could find. When their vanguard went by the ambush, Chabrias' men came out and hurled javelins and stones at the enemy. The hoplites came into action at the same time. The men in the vanguard, who were not marching information, were killed, including Gorgopas and the other Spartans - the rest turned and fled. "[Hell. 5.1.10].

Indiscipline Leads to Danger

Another important characteristic of peltasts is that they were generally lacking in discipline compared to hoplites and cavalry. They often charged impetuously without support, sometimes against superior enemy, thus bringing trouble upon their own heads.

During the march of the Ten Thousand, Xenophon describes an incident of this impetuosity causing their own rout: "When the Greeks were drawing near, the peltasts raised the battle-cry and proceeded to charge upon the enemy without waiting for any order; and the enemy rushed forward to meet them, both the horsemen and the mass of the Bithynians, and they put the peltasts to rout."[An. 6.5.26].

This recklessness at times caused peltasts to charge cavalry in the open, a situation that could have only one result:

- "Now when the Olynthians saw the peltasts sallying forth, they turned about, retired quietly, and crossed the river again. The peltasts, on the other hand, followed very rashly and, with the thought that the enemy were in flight, pushed into the river after them to pursue them. Thereupon the Olynthian horsemen, at the moment when they thought that those who had crossed the river were still easy to handle, turned about and dashed upon them, and they not only killed Tlemonidas himself, but more than one hundred of the others. "[Hell. 5.3.4].

The peltasts' lack of discipline also meant they were regarded as likely to pillage, as revealed by Xenophon's wry comment: "Then the peltasts, as was natural, started to plunder."[Hell. 3.4.24]. He again refers to this tendency to loot during the march of the Ten Thousand: "as soon as they began to cross the mountains, the peltasts, pushing on ahead and spying the enemy's camp, did not wait for the hoplites, but raised a shout and charged upon the camp."[An. 4.4.20].

The Peltast in Classical Greece

-

Preface and Introduction

What is a Peltast?

Speed and Maneuverability

Equipment and Function

Effectiveness in Battle

Conclusion and Bibliography

Peltasts in Action Diagram (27K)

Peltasts on Attic Amphora (86K)

Peltasts on Attic Cup (73K)

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com