Etymology

To get some idea of how these troops functioned and their importance, we must understand something of the use of the word itself in our source texts. The word peltastai is usually said to originate from the word pelte (pelta), the name of the crescent-shaped shield used by many peltasts. [This due to Diodorus, 15.44.3. However, his passage seems wrong-minded, for he says, "the infantry who used to be called 'hoplites' because of their heavy shield had their name changed to 'peltasts' from the light pelte they carried." This is clearly wrong. The evidence of Nepos is no better].

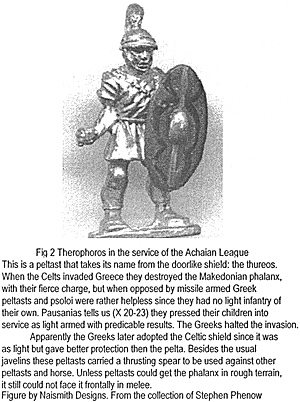

Fig 2 Therophoros in the service of the Achaian League

This is a peltast that takes its name from the doorlike shield: the thureos. When the Celts invaded Greece they destroyed the Makedonian phalanx with their fierce charge, but when opposed by missile-armed Greek peltasts and psoloi were rather helpless since they had no light infantry of their own. Pausanias tells us (X 20-23) they pressed their children into service as light armed with predicable results. The Greeks halted the invasion.

Apparently the Greeks later adopted the Celtic shield since it was as light but gave better protection then the pelta. Besides the usual javelins these peltasts carried a thrusting spear to be used against other peltasts and horse. Unless peltasts could get the phalanx in rough terrain, it still could not face it frontally in melee. Figure by Naismith Designs. From the collection of Stephen Phenow.

This assumes that the word pelte predates peltastes, but this is far from clear. There is for example a word older than both pelte and peltastes, the verb pelo, used as early as Homer, which means `to move around' or `to be in motion'. [The third person plural Doric form, pelonti (3p pl), and the deponent form, peletai, are especially reminiscent of the word peltastai. Note that the word pelte also refers to a horse-ornament, as well as a spear]. It seems quite possible that the Greeks named the peltast after this word, which describes these troops admirably, and then extrapolated from there the term for the shield used by the most common type of peltast in their world, the Thracian. [The crescent-shaped shield was also used by many Anatolian peoples, such as the Paphlagonians, as well as Skythians. Herodotus mentions the pelta in his description of the Thracian force that joined Xerxes, though he does not use the term peltast [(His 7.75.1)].

There were in fact other types of such troops known to the Greeks that did not use crescent shields but small round shields, and the term peltastai refers to just such troops. Furthermore there are plenty of depictions of mounted troops carrying crescent-shaped shields, as well as various kinds of infantry, especially foreign peoples.

[See for example p. 179 in L'autre Guerrier where can be seen Black Ethiopian troops with peltas but armed with axes; vase g102 in the Louvre for a Phrygian or Skythian with pelta; image 360 in Boardman's Athenian Red Figure Vases for an `Easterner' with bow, axe and pelta; Harvard vase Fogg 1959.219 for a Thracian with boots, cloak, pelta and long spear, and Ferrara [41] for a soldier carrying both a large hoplite spear with sauroter (butt-spike) and a pelta. Note too that a passage in Aristophanes' Lysistrata reveals that the 'Skythian police' of Athens carried peltas (line 563)].

A chance passage in Xenophon's Anabasis provides a rare literary insight into light infantry equipment: "A man of Mysia, who was called Mysus, took ten Cretans, stayed behind in some undergrowth, and pretended to be trying to keep out of sight of the enemy; but their shields [peltai], which were made of bronze, would now and then gleam through the bushes." [Anabasis, 5.2.29. Note that depictions of slingers with shields (which are rare) show the shields are rounded].

Thus, troops carrying a pelta can be cavalry, archers, or slingers, various foreign peoples, as well as the more commonly accepted peltast; similarly, 'peltasts' did not always carry a pelta. [For mounted troops with peltas see vase 1963.25 in Dusseldorf In fact, we cannot even be sure that a pelte refers to a crescent-shaped shield. Later sources imply any small shield may be meant (see Snodgrass, p. 78)].

Terminology

The definition of the peltast is itself complicated by the often-loose terminology of the Greeks. Plato says, `...we must hold a general tournament for peltasts, who will compete with bows, shields, javelins, and stones thrown either by hand or by sling."[Laws 834a]. Thucydides in The Peloponnesian War refers to 1,200 Thracian peltasts, which he refers to as swordsmen (machairophoros) in the same sentence [7.27.1].

Even Xenophon, the most militarily precise of our historians, often lapses into very loose definition: "The peltasts attacked right away, throwing javelins, hurling stones, shooting arrows and discharging slings... "[Hellenica, 2.4.33]. Xenophon also uses the word peltast to describe the troops of Persia, Phrygia, Paphlagonia, Cappodocia and Lydia in his Cyropaedia [E.g. 2.1.5]. Ordinarily we do not think of archers, slingers, or stone-throwers as peltasts; in our sources the former are usually referred to as toxotoi, sphendonetes, and psiloi or gymnetes respectively. The 'peltast,' then, is in fact quite an elusive character, and it is not always easy to know how exactly these troops were armed or armored.

We should therefore judge the peltast by his behavior rather than his equipment, though naturally there is some overlap between the two. Whether carrying crescent, circular, or oblong shield, whether armed with javelins, spears, swords, slings, bows or a combination of these, and whether completely unarmed or wearing armour, what he did, how he functioned in war, is what is important. The behavior of peltasts in our texts can be said to be the result of particular characteristics; these are discussed below.

The Peltast in Classical Greece

-

Preface and Introduction

What is a Peltast?

Speed and Maneuverability

Equipment and Function

Effectiveness in Battle

Conclusion and Bibliography

Peltasts in Action Diagram (27K)

Peltasts on Attic Amphora (86K)

Peltasts on Attic Cup (73K)

Back to Strategikon Vol. 2 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com