With the suicide of Nero in 68 CE the empire went through a period of anarchy known as the 'Year of the Four Emperors.'

Othoian Command group; left to right, Rufus

Proculus, Praetorian Prefect, Lucius Otho Titianus, the Emperor's

brother, and Suedius Clemens. Figures 25mm by RAFM, Grenadier

and Lamming, painting and photo by SFP.

Othoian Command group; left to right, Rufus

Proculus, Praetorian Prefect, Lucius Otho Titianus, the Emperor's

brother, and Suedius Clemens. Figures 25mm by RAFM, Grenadier

and Lamming, painting and photo by SFP.

The first of the four new emperors was Servius Sulpicus Galba, the propraetor of Hither Spain who had rebelled against Nero's rule with the help of his legio the sixth. He took office with the support of the Senate and the Praetorian Guard, but ignored the person who had brought him the purple, Lucius Otho, the Governor of Lusitania province in southwest Spain.

When hearing that the 72 year old Galba was going to name a different person as his successor, Otho went to the Guard, who themselves were dissatisfied with the emperor's stinginess. Otho promised lavish rewards to those who would get him the purple. Fifteen Praetorian Guards, so encouraged, organized a revolt in which Galba and his adopted son were killed in Janus 69, and handed the office to Otho (Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars "Life of Otho." 5, 6). But as Tacitus noted in "The Histories": "The secret of Empire was out, Emperors could be made elsewhere than in Rome." (Tact. History 1. 50)

Indeed soldiers stationed outside Rome decided to become involved. The legions in Germania and the Rhine had once been commanded by Galba and were fond of him. When it was heard that Otho had been proclaimed Imperator after murdering their former General, the legate of lower Germany, Fabius Valens, acclaimed his general and the Governor of lower Germany Aulus Vitellius as Emperor, and the legate of higher Germany, Alienus Caccina followed suit. (Tact. I. 57.) Vitellius accepted the commission of being Galba's avenger and he and his followers prepared to march on Rome with two legiones, 21st Rapax and 5th Alaudae, and vexillarii from six more. Tacitus tells us: "After the force from Britannia had joined him (three vexillarii from the 2nd, 9th, 20th probably 2,000-3,000 men, eight auxilii, 4,000 men).

Vitellius, who had now a prodigious force and vast resources, determined that there should be two generals and two lines of march for the contemplated war. Fabius Valens was ordered to win over the Gauls, if possible, or, if they refused his advance, to ravage the provinces of Gaul, and to invade Italy by way of the Cottian Alps. Caecina was to take the nearer route to Italy and to march down from the Penine range. To Valens was entrusted the picked troops of the army (i.e., the vexillarii from lower Germany legiones 4th, 10th, 15th, 1st) along with the 5th legion (minus two cohorts) and the auxiliary infantry and cavalry, (including the famous Batavi) to the number of 40,000. (This seems high unless Tacitus is including all the support personal. By my count Valens' force should be around 18,000 fighting men.) Caecina commanded 30,000 from Upper Germany, (again this seems high, 14,000 seems more likely.) his force being one legion, the 21st, one vexillatio each from the 1st and the 23rd, German auxiliaries, (which are later called from Gaul, Lusitania, and Rhaetia so they are not German at all [Tact. I. 70] ) and from this source Vitellius was later to follow with his whole military strength." (Tact. I. 61.)

Tacitus may be inferring that Vitellius was waiting for the rest of the army to assemble before following after his two legates. The British units couldn't arrive until sailing season commenced which was sometime in March. The campaign was well under way by then. The "source" might refer to the legionary base at Cologne. It allows for easy movement up the Rhine, and troops can move into Gaul, where Vitellius would be (at Lyons) when Cremona was fought. This is all speculation. Tacitus does not tell us. It also could be that Tacitus' numbers refer to all the troops under both legates at the end of the campaign in June.

Stop the Rot

Meanwhile Otho when hearing that the Vitellians were coming over the Alps mobilized his own forces. He started to lose troops in Cisalpine Gaul upper Italy to the Vitellians (no one likes a tyrannicide) including the Silius' horse and wished to stop that rot as quick as possible.

He sent the legio composed of naval marines once stationed at Misenum, now called Adiutrix (supportive) still in the capital for Nero's aborted 68 CE campaign, and detached 5 cohorts of Praetorians. There were Italian auxiliaries as well, including 2,000 Gladiators. He had Annius Gallus, and Vestricius Spurinna in command. He ordered Spurinna to take 3 cohorts of the five guard (1500) and occupy the Padus to contest Caecina's crossing (Tact. II. 12.) He planned to join with his loyal forces from Pannonia and Dalmatia. He followed several days later with the rest of the Praetorians in Rome (2,000), the guard horse (Equites Singularies) (500) and citizens' levies (3 cohorts 1,500?) and his household. (Tact. I. 87.)

His expedition did not fair well in its beginning. To quote Plutarch: "As to the prodigies and apparitions that happened about this time, there were many reported which none could answer for, or which were told in different ways; but one which everybody actually saw with, their eyes, was the statue, in the capitol, of Victory carried in her chariot with the reins dropped out of her hands, as if she were grown too weak to hold them any longer; and a second, that Gains Caesar's statue in the island of Tiber, without earthquake or wind to account for it, turned round from west to east; and this was a most unfortunate prodigy.

But now when the news came that Caecina had possessed the Alps, Otho sent Dolabella, a patrician who was suspected by the soldiery of some evil purpose, for whatever reason, whether it were fear of him or of anyone else, to the town of Aquinum, (base of Silius' horse) to give encouragement there, and proceeded then to choose which of the magistrates should go with him (Otho) to the war, he named amongst the rest Lucius, Vitellius brother without distinguishing him by any new marks' either of his favor or displeasure." (Plutarch Lives. Otho) Since had luck started with the expedition the Romans felt that Otho would have a hard time in prevailing.

Meanwhile Caecina had accepted the defection of Silius' horse, a loyal Galbian formation. The valley of the Padus (Po) was open. (Tact. II. 17) He captured 1,000 marines, and 100 horse, during his advance as well as a cohort of Pannonians near Cremona. (Tact. II. 17.) He found out that the 13th legio from Pannonia was near by.

This was because the 13th was responding to Otho's request to come to Italy. The Armies of Pannonia and Dalmatia were all sending troops: "These comprised of 4 legiones from each (army) of which 2,000 troops had been sent on in advance. The 7th had been raised by Galba, the 11th, 13th, and 14th were all veteran soldiers." (Tact. II. 11.) The 13th and the auxiliaries from Pannonia were in the advance, around 5,000 men.

As Caecina moved deeper into the valley of the Padus he decided to advance against Placentia (It. Piacenza). By taking this fortress city, at the junction of Po and the Trebia rivers, he could have a base of operations as well as a secure place to await Valens. He discovered the Othoians had rushed advanced forces under the command of Spurinna to Placentia. These were 3 cohorts of Praetorians, 2 cohorts of veteran citizen Auxilii (one is called the 17th Cob.) and a "handful of horse." (Tact. II. 18.)

Vitellian Command group; Caecina Alienus

(mounted) Figures 25mm Wargame Foundry, painting by Joe

Nacchio, photo by SFP.

Vitellian Command group; Caecina Alienus

(mounted) Figures 25mm Wargame Foundry, painting by Joe

Nacchio, photo by SFP.

The Vitellians under Caecina prepared to storm the place. They had already been successful in several skirmishes as they advanced across the Po valley, and their war fever was very high. Caecina attempted to get them to wait for Valens, but the impetuous army wished to attack right away.

Tacitus tells us what happened next. "The first day, however, was spent in a furious onset rather than in the skillful approaches of a veteran army. Exposed and reckless, the troops came close under the walls, stupefied by excess in food and wine. In this struggle the amphitheater, a most beautiful building, situated outside the walls, was burnt to the ground, possibly set on fire by the assailants, while they showered brands, fireballs, and ignited missiles, on the besieged, possibly by the besieged themselves, while they discharged incessant volleys in return."(Tact. II. 21) By nightfall Caecina been repulsed with "great slaughter." His losses had come from the auxiliaries, mostly Germans. (Tact. II. 24)

Both sides prepared during the night for the following day's assault. The Vitellians constructed siege equipmentmantlets, pelvises, and ramming sheds, (apparently they had no artillery) while the Othoians cut timber for stakes and gathered the stones of buildings and heavy lead fittings to break up the ranks of storming troops. (Presumably this was for the catapults, Tacitus doesn't make it clear) The Praetorians and Italian cohorts engaged in a friendly rivalry seeing who was faster in carrying out these tasks. Their morale rose, accordingly.

Dawn

As dawn came the walls were crowded with defenders, and the plains surrounding the city had around 12,000 armed men ready to attack. Once it was light the attack began. Tacitus continues: "The close array of the legions, and the skirmishing parties of auxiliaries assailed with showers of arrows and sling stones the loftier parts of the walls, attacking them at close quarters, where they were undefended, or old and decayed. The Othoians, who could take a more deliberate and certain aim, poured down their javelins on the German cohorts as they recklessly advanced to the attack with fierce warcries, (the baratis) brandishing their shields above their shoulders after the manner of their country, and leaving their bodies unprotected.

The soldiers of the legions, working under cover of mantlets and hurdles, undermined the walls; threw up earthworks, and endeavored to burst open the gates. The Praetorians opposed them by rolling down with a tremendous crash - ponderous millstones, placed above for that purpose.. Beneath these many of the assailants were buried, and many, as the massacre increased with the confusion and the attack of the walls became fiercer, retreated wounded, fainting and mangled... with serious damage to the honor of the storming army." (Tact. II. 22.)

Caecina gave up. He had lost perhaps a quarter of his army. Since they do not appear at First Cremona, his legio loss must have been from the vexillarii of the 1st and 13th. He had greater losses in auxilia as would be expected. (Tact. II. 22.)

Balked at seizing Placentia, Caecina next determined that Cremona would be his base of operations. Since he had only the one viable legio the 21st, he decided to retreat to the Padus, cross, and advance on to Cremona, before the Othoians could react. Polybios tells us that "It (Cremona) was Latin colony, which was founded in 218 B.C. as a bulwark against Gallic Insubres and Boii on the north bank of the Po." (Polyb. 3.40;) "Crernona staunchly supported Rome against Hannibal, although thereby it suffered so severely that in 190 it required additional colonists" (Livy XXI. 27.10). Its territory was confiscated for a colony of Roman veterans circa. 41 B.C.E. (Erg. Ed. IX. 28). Thereafter it was an important road center. If Caecina could seize that town, he could slow down the advance of Otho's reinforcements from Dalmatia.

Spurinna let him go. He sent a warning to Gallus who was marching to his relief with the "supportive" legio, the First. Gallus halted at Bedriacum, and started to fortify. Tacitus says that this was a village between Verona and day's march from Cremona and on the via Postumia.(Tact. II. 23) It was to be the rallying point for the Othoian forces. The problem is we do not know where it is today.

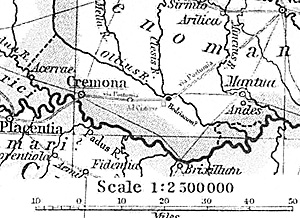

We can make an educated guess. (see map) We know it was east of Cremona. Plutarch says it was 150 furlongs away. (Plutarch, Otho) This puts it 16.9 miles away. Sixteen

miles is a normal day march for Romans so sixteen miles is likely

correct. It was here that Otho would concentrate his scattered army.

Also a good tactical commander, Suetonius Paulinus (victor over

Boudicea), and vexillard from his former legio, the 14th, (2000 men)

had arrived. (Paulinus from Rome, the 14th from Moesia). ne

Praetorians from Rome (2 cohorts), the 13th from Pannonia (3000?

It had its eagle) and the 1st Adiutrix, as well as Paulinus' vexillarii of

the old 14th gave Paulinus and Marius Celsus a strong force to

operate with. Paulinus quickly went on the offensive. Caecina,

meanwhile had to do something. Valens had been delayed. Vitellius

was somewhere in Gaul, and the Othoians were becoming stronger.

He also discovered that an army commander in a civil war had to

have successes, otherwise

the troops would stop listening to him. He needed a victory. So he

planned to ambush a unit of the enemy while it was scouting, destroy

it, to regain his men's favor.

We can make an educated guess. (see map) We know it was east of Cremona. Plutarch says it was 150 furlongs away. (Plutarch, Otho) This puts it 16.9 miles away. Sixteen

miles is a normal day march for Romans so sixteen miles is likely

correct. It was here that Otho would concentrate his scattered army.

Also a good tactical commander, Suetonius Paulinus (victor over

Boudicea), and vexillard from his former legio, the 14th, (2000 men)

had arrived. (Paulinus from Rome, the 14th from Moesia). ne

Praetorians from Rome (2 cohorts), the 13th from Pannonia (3000?

It had its eagle) and the 1st Adiutrix, as well as Paulinus' vexillarii of

the old 14th gave Paulinus and Marius Celsus a strong force to

operate with. Paulinus quickly went on the offensive. Caecina,

meanwhile had to do something. Valens had been delayed. Vitellius

was somewhere in Gaul, and the Othoians were becoming stronger.

He also discovered that an army commander in a civil war had to

have successes, otherwise

the troops would stop listening to him. He needed a victory. So he

planned to ambush a unit of the enemy while it was scouting, destroy

it, to regain his men's favor.

The Othoians were watching the camp at Cremona. Caecina planned to advance to the temple of Castor and Pollex 12 miles from Cremona. Plutarch tells us what happened next: "Caecina placed a strong ambush in the rough and woody country, and gave orders to his horse to advance, and if the enemy scouts were to charge them, then to make slow retreat and draw them into the snare." However, deserters (a constant problem in any civil war) informed Paulinus of the trap, and he set one of his own. He took a vexillatio from veteran 13th , as well as 2 cohorts of Praetorians, the Equites and assorted auxiliaries. He blocked the via to the south with 2 cohorts of the First. He made sure that the 13th and Praetorians were well bidden on either side of the road. When the Vitellians pursuing the fleeing enemy horse came down the road, it was they who fell into the trap. "Then the Othoian infantry charged. The line was completely crushed, and the reinforcements who were coming up to their aid were also put to flight. Caecina indeed had not brought up his cohorts in a body, but one by one; as this was done during the battle, it increased the general confusion, because the troops who thus divided, were not being strong at any one point, and were swept away by the panic of the fugitives. "Tact. II. 26.)

Paulinus has been censored by modem historians for not finishing the job, as well as Tacitus, claiming that whole Vitellian force was in a panic. But his lack of pursuit made sense. After all he had no real idea where his enemies' main forces were, and if what Tacitus tells is correct, there was a lot of Vitellians strung out along the Via. Even though the Othoians were successful, they won only through the element of surprise. They didn't outnumber the entire enemy, and Paulinus sensibly called off the pursuit. And what with soldiers being soldiers, the troops didn't understand, (it is interesting how in a civil war everybody is a leader and military genius) and suspected that Paulinus had been bought off by Caecina. He returned to the camp with the disgusted forces.

It didn't take long for the emperor to hear this rumor about Paulinus loyalty. "He came up from Brixellum where he had established his residence, to meet with his generals and bring his along his brother, and the Practorian Prefect Licinius Proculus, an evil man." (Suetonius: "Otho" 8)

Whatever happened in this meeting, Paulinus and Celsus at least tried to talk the emperor into stalling the advance. The rest of the 14th Gemina (Martia Victrix) "whose men had covered themselves in glory while quelling the revolt in Britannia.. Nero had enhanced their reputation by putting in the forefront of all his forces, transferring them to Italy, - thus their devotion to him and their willingness to fight for Otho ... would appear on the scene in several days - supplemented by forces from Moesia." (Tacitus II.32)

Tacitus now goes on to talk about bow Paulinus attempted to talk the emperor into reaching the settlement with Caecina. Vitellius was still not on the scene. Actually, this wasn't a bad idea. Caecina's men were convinced that he was somehow was in league with the Othoians, after all he lead them to two defeats. No doubt he'd been willing to talk at least, Suetonius says. But things changed again. The news came that Valens had arrived at Cremona, and that the enemy was trying to outflank the Othoian position. (Suetonius "Otho" 9.)

Valens had an eventful trip. He had poached the newly enrolled 1st Italica and an ala of horse (Taurine) from Lugdumm (Lyons) (Tact I. 65). As he moved out of Gaul into Cisalpine the Othoians landed a force from the fleet on their flank. In Gallia Narbonensis near the colony of Forum Julii the naval forces were ready to advance. Valens sent back two cohorts. and four alae of Germans and had the detachment commander (Julius Classicus, commander of the Teverian horse) raise all the horse of the province to defeat the landing. They fought several engagements which resulted in the Vitellians being worsted. Classicus retreated farther back into Gallia Narbonensis. The Othoians advanced to Albigaumn in Liguria. (Tact. II 15.)

While in Liguria a Batavian unit arrived which had been stationed. With the 10th in Britannia and had been ordered back to the island. Valens' army was in a mutinous mood and the auxilia had brought information to Valens: namely that the 14th was no longer in Moesia but on the move into the Padus Valley. Valens, upon bearing the Othoians had won at Forum Julii and that Narbonensis was blockaded, sent the Batavians back to give support to Classicus.

Mutiny

This was the spark that ignited a major mutiny among Valens' troops. The Batavians, gallant men and conquerors of the Britons, had been ordered away just when the army needed thern the most. With cries of "he hides the spoil of Gaul!" the legionaries threw stones at him, and Valens fled for his life disguised as a slave. The legionaries ransacked his baggage, and dug trenches looking for the loot. When they didn't find any, the mutiny burned itself out and Valens was able to resume command. (Tact. II 28.29)

Valens had been at Ticinum, (Pavia) resting and refreshing supplies when news of the defeat at the Castors arrived. His troops were in a fury because they had missed battle, and forced Valens to continue movement towards Cremona at once. He obeyed realizing that "...in civil wars the soldiers have more license than the generals" (Tact II. 29)

Caecina meanwhile, was attempting control his own army. He attempted the time honored stratagem of keeping disaffected troops busy by building a bridge to the south side of the Padus, and he shifted the blame to Valens. "After all" he said, "he had the bigger army, and where is he?" This bridge was important because the Othoians had been raiding the north side of Cremona using their own bridge and Caecina was finally able to destroy it. (Tact. II. 34.)

When Valens arrived he found that the situation in Caecina's army was that they thought he, Valens., was no better than a traitor, and his own army agreed with them. Caecina was to be supreme commander. Tact. II. 35,36)

The bridge building was resumed. The Othoians attempted to block it and were defeated. With the bridge the Vitellians could bypass the blocking force and march on Rome. This made up Otho's mind. He would not wait. The Practorians had arrived from Placentia and informed the Emperor that Caecina had been badly hurt. These Praetorians also tipped the balance of power.

He now had 7 cohorts of Praetorians, the 1st Adiutrix (though raw was at full strength 5,000), the 13th Gemina, with its eagle (at least seven cohorts 3,600) and the vexillarii from the 14th Gemina, (four cohorts 2,000) as well as Moesian, Pannonian, and Italican auxiliaries facing 21st Rapax (eight cohorts), 1st Italica (with nine cohorts but raw like his First), 5th Alaudae, (probably seven cohorts) and the vexillarii from six legiones (6,000) He would attack!

He replaced Paulinus and Celsus with the Prefect Licinius Proculus, along with his brother Titianus Otho overseeing operations. His plan was simple. He would reinforce the gladiators on the south side of Padus, with two cohorts of Praetorians. The main army would advance to the bridge location and set up camp, cutting its access. If the Vitellians attacked more the better; it would show Rome that Otho did not want civil war, it was forced on him. If the Vitellians did not attack, then by the end of the week he would have the rest of the "fighting" 14th with vexillarii from 7th Galba, and the 11th plus their auxiliaries. That should be enough to get the force of Caecina to surrender.

With this plan ready to be put in operation he now made, in Tacitus estimation, a huge mistake. He let himself be persuaded to return to Brixellum with a cohort of Practorians and a cohort of Italican auxiliaries (Tact. II. 33. 39). Plutarch agreed: "Hehimself returned to Brixellum. This was another false step, both because he withdrew from the combatants all the motives ofrespect and desire to gain his favor which his presence would have supplied, and weakened the army by detaching some of his best and most faithful troops for his horse and foot guards." (Plut. "Otho")

By replacing his best Generals with two incompetents he was sending a clear message to the Legates and Tribunes and Prefects of the army, that he did not trust his best men to lead them. This must mean that the battle was as good as won, why else would he have done this?

So the Othoians advanced into an important battle with no faith in their generals, no emperor to inspire them, and each unit commander believing that some sort of deal must have been struck with the enemy to allow this to happen. It was a recipe for a disaster. Plutarch sums the man up quite well: "Otho also himself seems not to have shown the proper fortitude in bearing up against the uncertainty, and, out of effeminacy and the want of use, had not the patience for the calculations of danger and was so uneasy at the apprehension of it that he shut his eyes, and like one going to leap from a precipice, left everything to fortune." (Plut. "Otho")

Fortuna can be a fickle goddess as Otho was about to find out.

More Battle of 1st Cremona

Back to Strategikon Number 1 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com