So where did the battle occur? Historians call it the battle of Bedriacum based on Tacitus' statement in Histories "Vitellius then directed his course to Cremona, and after witnessing the spectacle exhibited by Caecina, he conceived a desire to visit the plains of Bedriacum and to survey the scene of the recent victory." (Tacitus II.70.)

How accurate is Tacitus? He was born in the 50's in Northern Italy, or France (theories differ). He knew the area quite well. His father-in-law Agricola also came from there. He knew Vestricius Spurrina from interviews in the Senate, and his recollections about Placentia arereasonably correct for that reason. Spurrina may have exaggerated some, like old soldiers tend to do, but the friendly rivalry between the Praetorians and the Urban cohort the night of the siege has a ring of truth to it, something the garrison commander would recall. That is not to say that Tacitus is unbiased. Alas no. In fact, since he is writing for the Flavian dynasties, be disparages both Otho and Vitellius so much that it becomes tedious. Neither is fit to rule so naturally they are replaced by the Flavian Vespasian. Nevertheless I believe his account is reasonably truthful.

Our next source is the "Parallel Lives" of Plutarch. Plutarch lived even longer then Tacitus. Likely he was also born in the 50's so he may have been in his 20's when Cremona occurred. However since he was a Boeotian, he probably didn't even know of the battle until well after the fact. But he must have been in contact with at least one creditable eye-witness. We infer this because of the rich detail he includes in the scenes. He also has an insider view of the principal characters and the emotions. Plutarch tells us it was Senator Mestrius Florus in his 'Life of Otho.' Florus was at Brixellum with Otho, he saw the field after the suicide of Otho, on his way to submit to Vitellius. Plutarch himself visited the field, he tells us in the Otho story. Since we must assume that both authors are reasonably accurate, then nailing down the field's location becomes easier.

The purpose of the campaign was to pen up the Vitellians so that they couldn't bypass Otho's growing forces coming down from the Danube. The main body was 14th Gernina, as well 8 cohorts from each: 7th Galbiana, 5th Macedonica, 4th Scythia, 7th Claudia, and their Moesian and Thracian auxiliaries. (Tact. II 32-33)

To do this they had to destroy the bridge that Valens and Caecina were building that would allow the German anny to cross to the south side of the Po and escape. The bridge was at the joining of Po and the Addua. (Tact.II 40.) The road to the confluence takes one through the town of S. Giacomo Lovara. The ground to the north between the Via Postumia and the village of S. Savino is heavily wooded with vineyards and ditches for drainage. On the south side, once you are past the drainage ditches that drain the Via, the ground is more rolling, covered in occasional vineyards and ditches. This fits the battleground as described in Tacitus and Plutarch. It is five miles from Cremona, and 18 miles from the proposed location of Bedriacum.

The Battle Begins

The Battle Begins

The Othoian army, under the command of L. Otho Titianus, started out badly.

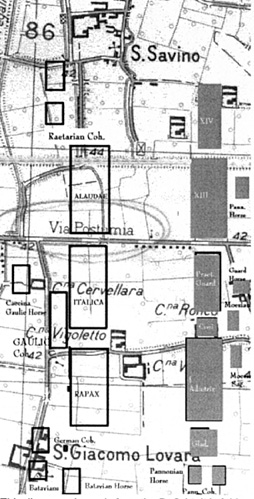

Historical dispositions except for gladiators at bottom right, who were not at the battle.

"It was resolved to move the camp forward to the fourth milestone from Bedriacum, but it was done with such a lack of skill, that though it was spring, and there were so many rivers in the neighborhood, the troops were distressed for want of water. Then the subject of giving battle was discussed, Otho in his dispatches was ever urging them to make haste, and the soldiers demanding that the Emperor should be present at the conflict; many begged that the troops quartered beyond the Padus should be brought up. It is not so easy to determine what was best to be done, as it is to be sure that what was done was the very worst." (Tacitus II 39.) Plutarch: "Proculus led them out of Bedriacum to a place fifty furlongs off, where he pitched his camp so ignorantly and with such a ridiculous want of foresight that the soldiers suffered extremely for want of water, though it was the spring time, and the plains all around were full of running streams and rivers that never dried up." (Plutarch "Otho")

The next day L. Otho Titianus advanced to his objective.

He apparently decided to advance along the Via, with his cavalry in the lead. "They started for a campaign rather than for a battle, making for the confluence of the Padus and Addua, a distance of sixteen miles from their position. Celsus and Paulinus admonished against exposing troops wearied with a march and encumbered with baggage to any enemy, who, being himself ready for action and having marched barely four miles, would not fail to attack them, either when they were in the confusion of an advance, or when they were dispersed and busy with the work of entrenchment." (Tacitus II. 40)

"The next day he proposed to attack the enemy, first making a march of not less than a hundred furlongs; butto thisPaulinus objected, sayingthey ought to wait, and not immediately after such a journey engage men who would have been standing in their arms and arranging themselves for battle at their leisure, whilst they were making a long march, with all their beasts of burden (each 8 man tent unit had a donkey to carry their tent, since this was a campaign, everything had been brought along.) and their camp followers to encumber them." (Plutarch Otho.) No matter, the march went on. By midday the Vitellians became aware of the columns' slow approach and mustered arms. The first battle for Cremona was about to began.

The battle opened with a cavalry clash. The cavalry screening the Othoian advance were set upon by the German horse. The Parmonians and Moesians were up to the task. They drove the Vitellians back. The cavalry routed back to the Vitellian camp, and there " were kept only by the courage of the Italican - (Italica, who, apparently, was the vanguard) from being driven back on the entrenchments by an inferior force of Othoians. These men, at the sword point, compelled the beaten regiments (alae) to wheel round and resume the conflict." (Tacitus II 41) "So while the legions took up their position in the march, they sent out the best of their horse in advance." Plutarch Otho.

With the Italica in the lead, the Vitellian column marched towards the Othoians. We know the camp was 3 miles from the confluence. (Tact II 41) This would make it 4 miles to crossroads. If the Vitellians were averaging around 3 miles an hour then after a hour and 10 minutes they would be approaching the road junction. Apparently they only knew that there enemy was close by scouting reports from their horse. The terrain precluded any vision. Yet the troops were strangely disciplined, their last two defeats had left a mark on them. "The line of the Vitellians was formed without worry for, though the enemy was close at hand, the sight of their arms was intercepted by the thick brushwood." (Tact. II.41)

With the Vitellian army cutting them off from the crossroads, (a small grace since if the army was moving down the S. Giacomo Lovara road they would have been taken in the flank) the Othoians had to form for battle. For some reason a panic swept through the ranks, and was quelled by some officer saying that the war was to be avoided due to a rebellion in the ranks of the Vitellians.

"In Otho's army the generals were full of fear, and the soldiers hated their officers; the baggage-wagons and the camp followers were mingled with the troops and as there were deep ditches on both sides the road, it would have been found too narrow even for an undisturbed advance. Some gathering round their standards, others were seeking them, everywhere was heard the confused shouting of men were joining the ranks, or calling to their comrades, each, as he was prompted by courage or by cowardice, rushed on to the front, or slunk back to the rear. From the consternation of panic their feelings passed under the influence of a groundless joy into languid indifference some persons spreading the lie that Vitellius' army revolted." (Tact. II. 41, 42)

This rumor quieted the troops and restored discipline, but at a cost, because when the Vitellians did not come over it caused dismay. Of course by this time the army was starting to fight for its lives, so the feeling was quickly ignored.

The ground was not suited for fighting with legions or horse. The Vitellians' superior number of auxiliaries would definitely add some advantage, and the Othoians had to form battle line where they were on the Via. "And nothing else that followed was done upon any plan; the baggage carriers, were mingling up with the fighting men; created great disorder and division; as well; as the nature of the ground, the ditches and pits in which were so many that they the troops were forced to break their ranks to avoid and go round them, and so, had to fight without order, and in small parties." (Plut. Otho)

I Adiutrix was formed from the two naval marine regiments stationed at Misenurn by Nero in 68 C.E. The raw unit nearly defeated the veteran XXI Rapax at Cremona. Figures 25mm by Minifig, Foundry and others. Painted by Joe Nacchio and Stephen Phenow. Photo by SFP.

The first Marine legio Adiutrix (Supportive) had moved off the Via and had formed up into duplex acies in the fields. While the ground was not the best, there were still vine props and ditches, there were also fields of millet and barley. There were many small farm dwellings around but the legio could still maneuver in lines in the time honored tradition. However it was newly formed and except for being involved in police duties in Rome, and the skirmish at Ad Castors, untried. It was facing the twenty first Rapax (Graspers) an old legio. Originally founded by Augustus (Corpus Inscriptionuin Latinarum, V. 4858, 4892, 5033.) it had been based at Vetera. (Tact. Ann. II 79) It had taken part in Augustus' pacification program of Ractia, helped put down the revolt in Dalmatia, and was transferred to Germania after the Varius disaster. There it had taken part in Tiberius', Drusus' and Germanicus' reprisals against the Germans. It would appear that the Nero-founded Adiutrix was in over their head.

Surprises

What happened next was surprising. "In an open plain between the Padus and the road legions happened to meet. On the side of Vitellius was the 21st called the Rapax, a corps of old and distinguished renown. On that of Otho was the 1st, called Adiutrix, which had never before been brought into the field, but its' spirits were high and eager to gain its first triumph. The men of the First, overthrowing the foremost ranks of the 21st, carried off the eagle" (Tact. II 43.) Plutarch is more laconic: "There were but two legiones, one of Vitellus called The "Ravenous"(Plut. Is using Greek here to describe the Latin title,) and another of Otho's, called The Assistant, (again Greek) that got out into the open, out-spread level and engaged in proper form, fighting, one main line against the other, for some length of time. Otho's men were strong and bold, but had never been in for battle before; Vitellius' had seen many wars, but were old and past their strength. So Otho's legio charged boldly, drove back their opponent, and took the eagle, killing pretty nearly every man in the first line." (Plut. Otho)

Not only did the green legio defeat the veteran one but took its Eagle as well. Now the Eagle was the sacred symbol of the legio. It is consecrated on the legio's birthday every year, and the Eagle bearers are priests, wearing hoods of animal skins covering their heads. They will only relinquish their charge if killed and that was what happened. Plutarch might be exaggerating about killing everybody in the first line, but there is no doubt that Rapax had received an unexpected check.

Loss of the eagle and the defeat of the first line is bad news for a legio. Plutarch's account also talks about the legions being "spread-out" and engaged in "proper form." Since legions operated in lines, so one line could relieve the other, bringing fresh men against tiring ones, Plutarch seems to be saying that these two are the only ones that fought in this way. This would go far in explaining why the Othoians lost.

In the center, along both sides of the road the Praetorians met their old compatriots (they had trained together in Rome when Nero raised the legio) the First Italica. Neither had time to spread out, so they met each other "in loose or compact formations" (Tact. II. 42) The fighting was brutal, especial among former comrades. This was tragic thing about a civil war "where triends become enemies, enemies, friends." (Seut. Otho) Tacitus continues "...they stood foot to foot, (fighting hand to hand,) throwing the weight of their bodies and their shield-bosses against one another, and ceasing to throw pila, they struck through helmets and breastplates with swords and other camp weapons. Recognizing each other and distinctly seen by the rest of the combatants they were fighting to decide the whole issue of the war." (Tact. II. 42) The Praetorians and Italica were fighting in cohorts and centuries (centuriae), trying to gain an advantage over one another. There was no higher organization, this was a soldier's battle. The Practorians were outnumbered by Italica, but on such a narrow front it didn't matter.

To the north two other legions were fighting. On the Vitellian side was the 5th Alaudae (Larks). Alaudae had an even older tradition then Rapax. Founded by Julius Caesar himself (Seut. Caesar) from Transalpine Gauls (it's name is Gallic) it distinguished itself at Munda, killing several Pompeian elephants. Because of this feat, it was given an elephant badge. (Appian Bellum Aftica I.5.)

It was facing a slighter younger legion, the 13th Gemina (Twin) The title "Gemina" according to Caesar was to show when a legion was combined with another usually after both bad suffered crippling loses. The 13th could trace its lineage back to Augustus who raised them from Caesar's old vets at Spello. (Inscriptiones latinae selectae 6619a) in 41 or 40 B.C.E. They were at Puteloi (App. Bell. Civ. V. 87) and at Actium were acting as marines where they were badly crippled in the naval fighting. They were combined shortly after this with another legion. Neither unit had time to spread out in the battle. They probably both swerved off the road to the north since Italica and the Praetorians were blocking their advance. Alaudae got into position first, and scattered the 13th in very short time. "In another quarter the 13th legio was put to flight by the charge of the 5th." (Tact. II. 43.)

The Vitellian Legio 5th Alaudae (Larks), deployed triplex acie. Across the Via Postumia are the ranks of the 1st Italica.

The fate of the vexillarii of 14th Gemina was very sad. Here were the picked men, veterans all, from Nero's favorite legion, and with the 20th had destroyed Boudicea. They too could trace their linage back to Augustus, (40) were hurt at Actium, and also were combined with a another legio. They had taken part in all of Augustus' major campaigns and were with Tiberius and Drusus in Germania. They were sent to Britain as part of Claudius' invasion force, and after defeating the lceni revolt in 61 were transferred to Rome to take part in Nero's campaign against the East in 68.

At Cremona they were forced to operate in terrain that was not ideal for Romans. It was ideal for their German and Gaulic foes. All these were auxiliaries used to fighting in bad turf, which was the whole purpose of Augustus raising the arm. They were as heavily armed as the Romans, but designed to go in areas the legionary couldn't. Even though Augustus never foresaw this use for them, they were brutally efficient. Tacitus dismisses the fighting ability of the 14th in one line. "The 14th was surrounded by a superior force and overwhelmed." Plutarch never even mentions them. Thus is the epitaph of the 14th who took the highest number of casualties in the vineyards and orchards in front of S. Savo. (Senator Florus remembers seeing corpses piled up as high as the town's temple roof. - Plutarch Otho. ) The vexillarii is not reported in the history again. Its casualties were too high to allow its reconstruction.

Meanwhile on the plains, Rapax and Aduitrix were still fighting. Flushed with victory, but jumbled from battle, Aduitrix's first line was disordered when Rapax sent in its second line. What makes a veteran unit a good fighting machine, is its ability to overlook misfortune. This was the case with Rapax .

"...till the others, full of rage and shame, returned the charge, slew Orfidius, the commander of the legion, and took several standards." (Plutarch Otho.) Tacitus is more complete "The 21st, infuriated by this loss, not only repulsed the 1st and slew the legate, Orfidius Benignus, and captured many standards from the enemy." (Tact. II. 43) (These would be cohort standards called Imagos, or Signums.)

With the death of the commander the 1st fell back, followed by Rapax, and this opened a gap. Into this gap advanced the bridge guard, several cohorts of Batavians.

They had an eventful morning. Once the fighting began they had defeated the gladiators of the south side, then being free to maneuver their commander Prefect Varus Alfenius urged them to join in the fight. The war loving Germans (ancestors of the Swiss) needed no more encouraging. The auxiliaries advanced the intervening three miles at a trot and since they were arriving on from the south, were able to move behind Rapax and take the Praetorians in the flank "New reinforcements were supplied by Varus Alfenius with his Batavians. They had routed the band of gladiators, which had been ferried across the river, and which had been cut to pieces by the opposing cohorts while they were actually in the water.

Thus flushed with victory, they returned and charged the flank of the enemy." Plutarch tells us who that enemy was. "Varus Alfenus, with his Batavians, who are the natives of an island of the Rhine, and are esteemed as the best of the German horse and foot, fell upon the gladiators, who had a reputation both for valor and skill in fighting. Some few of these did their duty, but the greatest part of them made towards the river and, falling in with some cohorts stationed there, were cut off. But none behaved so ill as the praetorians, who refused to meet them and ran away, breaking though their own body, putting them in disorder."

With the rout of the Praetorians the battle was over. Rapax had bested Aduitrix, Alaudae had beaten Gemina, the 14th had been cut to pieces, and now the Praetorians were running away. Tacitus tells us "The center of their line had been penetrated, and the Othoians fled on all sides in the direction of Bedriacum, The distance was very great, (18 miles) and the roads were blocked up with heaps of corpses-, thus the slaughter was greater, for captives taken in civil war can be turned to no profit." (Tact. II. 44) Tacitus is remarking here on how the Roman army depended on the selling of slaves to maintain its operating revenues. It would rather capture a beaten army then destroy it. This was not the case in civil war. Here the low ranking captives were useless, and so were killed.

Aftermath

The routed army rallied in Bedriacum angry at one another at the defeat. There Annius Gallus told them that they should not fight among themselves, but wait to see what the morrow would be. The surviving Praetorians oddly were still full of fight "They gained no bloodless victory. Their horse was defeated, a legio lost its eagle. We still have the troops beyond the Padus, and the Emperor himself. The legiones of Moesia are coming, a great part of the army is still in the south. And if it so, it is on the battlefield that we shall fall with the most honor." (Tact. II 44.)

However the rest of the army did not feel the same, they had cast their die, and had not won. Envoys were sent to the enemy army now four miles outside the town. Before long they returned with the announcement that a truce had been declared and the camps were to be opened. There was to be no more fighting. Tacitus closes this portion of the narrative with these moving words. "Both victors and the vanquished melted into tears at the sight of one another and cursed the fatality of civil strife with a melancholy joy. There in the same tents did they dress the wounds of brothers or of kinsmen. Their hopes, their rewards; were all uncertain; death and were sure. And no one had so escaped misfortune as to have no bereavement to lament. Search was made for the legate Orfidius' body, and it was burnt with the customary honors. A few were buried by their friends; those that remained, were left above ground."

Plutarch: "When the Vitellian generals rode to the walls nothing was said to the contrary; those on the walls greeted his men with salutations, others opened the gates and went out, and mingled freely with those they met; and instead of acts of hostility there was not anything but mutual shaking of bands and congratulations, everyone taking the oath and submitting to Vitellius. This is the account which the most of those that were present at the battle give of it, yet owning that the disorder they were in and the absence of any unity of action, would not give them leave to be certain of its particulars."

So ended the Battle of Cremona. There would be another in three months time.

More Battle of 1st Cremona

Back to Strategikon Number 1 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com