Background

This section describes a wargame campaign, loosely based upon a series of raids the Huns made into the Eastern Eapire in 447. In a series of uncoordinated moves, parties of Huns attacked the Balkan provinces. It ended with the Huns reaching the sea at Helipolis and Sestus, Thrace devastated, the Roman army defeated in the Chersonesus where the Huns won their greatest victory ever, and Theodosius begging for terms. 6000 lbs of gold were paid in arrears, an annual tribute of 2100 lbs of gold was set, a large belt of territory south of the Danube was evacuated and handed over to the Huns.

At the start of the campaign, Attila'a power was not firmly

established - his army was one of three groups of Huns that

attacked the Eastern Romans. The other two groups were not under

his control. By the Autumn of 447 Attila, king, Commander in Chief

Supreme judge, was unconditionally obeyed (43).

At the start of the campaign, Attila'a power was not firmly

established - his army was one of three groups of Huns that

attacked the Eastern Romans. The other two groups were not under

his control. By the Autumn of 447 Attila, king, Commander in Chief

Supreme judge, was unconditionally obeyed (43).

The three groups were:

-

1) Attila and his army. If Attila had been unsuccessful in his

campaign then his rise to power would have probably ended there and

then.

2) A group of Huns, dissatisfied with their king, wanting gold and ready to go to war.

3) Huns already waging war on the Romans.

2 The Game

The caapaign is a three player game, each player controlling one of the groups of Huns.

The umpire regulates the game mechanics and controls the hard- pressed Roran army, which has limited initiative aa it has a set of defense priorities, mainly concerned with protecting Constantinople and Thrace (pre-programed tournament?). It must be stressed at this point that the umpire is not a player, so he cannot win with the Romans.

Philosophy. The game is to be played ln a kriegapiel, free-format sty1e, with game mechanics being minimal and simple - it is the umpire who regulates the flow a game, feeds information to the players, and resolves disputes and conflicts. Simple "luck" decisions are by throwing a dice where necessary. Many people believe a campaign is there to purely generate battles. I do not accept this. If you can win vithout a costly and risk, battle, then good for you. The battle is a means towards an end in the case of this game, for a player to accumulate as much booty (and hence also prestige) as possible during the campaign. Success, measured in gold in this game, will attract other tribes to the most successful leader, which in turn increases his political power. Having said this, a decisive win over the Roman field army will probably force Theodosius to ask for terms, and bring incalculable glory and wealth to the victor.

Assumptions The Hun armies will not usually fight each other, whatever their leaders may wish - there is more than enough booty available to the common warrior without having to resort to inter-tribal varfare in the middle of enemy territory.

The forces available are as follows. The figurs quoted are purely conjectural.

Roman field army: 12,000 men (suppleaented by local garrisons which remain with the town once the field army moves on).

Attila's army: 21,000 horsemen. Start position - anywhere on the Danube.

The second army: 19,000 horsemen, Start position - anywhere on the Danube.

The third army: 17,000 horsemen, already waging war on the Rooana Start anywhere within the empire bar Macedonia and Thrace. Start with 150 lbs of gold.

Game Objectives To get as much booty as possible. This is measured in lbs of gold. Ravaging the provinces and looting a city all produce gold. The value of an area or city is not known to a player beforehand. Sacking Conatantinople or humbling the Roman field army all produce suitable result. (think of all those slaves, all that ransom, and all that armour and weaponry) The game lasts 6 turns.

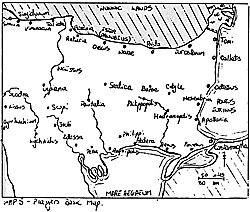

Players Information Each player gets a basic map of the region (see map 5) The umpire possess a more detailed map with notes on garrisoon strength, army location, etc recorded. Information is only given out when necessary or sometimes when asked (perhaps a player could try bribing the umpire with a case of beer). Players are given basic information on march rates, hints on chances of taking towns, etc. Thrace is known to be the richest province, Illyricum and Macedonia the poorest. Players will be interested to hear that the walls of Constantinople have just been destroyed by an earthquake.

Geme Mechanism The following is only intended as a rough guide. The game lasts six turns, each turn is approximately one week. A rough figure to man ratio of 1:100 is used.

Movement Rates There are a number of movement rates, which are themselves modified by a dice roll to give a variable move each turn.

-

Looting raiders: 60miles/turn (plus or minus 20 miles max) Travelling

at this speed the surrounding countryside is considered subject to

systematic plunder for a 25 mile radius. Heavily laden baggage also

travels at this rate.

Roman March: 120 miles/turn

Hun March:180 miles/turn (plus or minus up to 30 miles) Very little raiding is possible.

Force March:300 miles/turn (plus or minus up to 50 miles) No raiding possible. Attrition rate is 200 - 1200 men/turn (2D6)

Huns never have to maintain a supply line; the Roman field force alvays has to.

Looting The country raids generate 20 - 120 gold (2D6), modifiable by province A town provides 100 - 600 lbs gold (1D6) Constantinople yields 3,000 lbs of gold. A defeated field army is variable, depending on circumstance.

Danube towns fall on a 5,6 (1D6), other towns fall on a 4,5,6. Modifiers +1 surprise, +1 for a suitable bribe. If the initial attack is unsuccessful, a town will fall on a 6 (no modifiers). The Huns can attack a town twice per turn, but subsequent attacks (and some initial attacks) are subject to attrition (200 - 1200 men 2D6).

Constantinople Yes, the walls really were destroyed by earthquake during 447, while the Huns were raiding the region. They were hastily rebuilt. This option is to allow the possibility that a raid could have struck while the walls were down.

Constantinople will fall on a 5,6 if attacked, on turn 2 it will only fall on a 6. No modifiers. In each case, roll for attrition on the part of the attacker. Turn 2 the walls are considered rebuilt.

Plague The Huns frequently suffered from a plague on campaign - "a sickness of the bowels". A Hun army turned away from Constantinople because of plgeue. Attila's army wasn't affected so presumably his army was elsewhere.

2d6 per turn per player:

-

12 means plague

10 - 12 meana plague if continuing a siege into a second or subsequent turn, or if two Hun armies have combined forces.

9 - 12 means plague if a combined army is conducting a siege.

11 - 12 means plague if an army remains in an already looted and devastated region.

Plague Losses are 300 - 1800 per turn (3D6), and no one will want to come near you.

Conclusion

The Hunnic Empire'a collapse was as startling and violent as was its growth. Attila died in the winter of 452, of a nose bleed that choked him while asleep on the night of his marriage to Ildico. Vithin a year his empire had collapsed, and in 454 the Huns were decisively defeated by a coalition of German tribes lead by the Gepid kin8 Ardaric, at the battle of the Nedao River (and there, it strikes se, is a campaign in itself).

Why did the Hun empire collapae so quickly and thoroughly? Undoubtedly, his death was a major factor, but it is too simplistic to say the empire collapsed purely because Attila died. There were a number of factors at work. Both the Gallic caapalgn of 451 and the Italian campaign of 452 were disasterous for Attila and the Huns: too many dead warriora; too many lost horses. The Western government was not forced into subaission, with a consequent loss of tribute. The exploitation of the German subjects must have increased with the loss of the external revenues, remounts and loot; and the Hun nobles must have resented two years of failure. After his death, Attila's sons fought amongst themselves for the empire, with further discontent. Finally the German tribes revolted and a succession of battles were fought, culminating in the battle of the Nedao River. Hunnic pover was broken forever.

I hope you have enjoyed this article, and I trust by now you have a fair understanding and healthy respect for the Hun army in battle and on campaign.

Notes

1) Priscus fr.10, from Gordon, p58.

2) Priscus fr 23. Gordon.

3) Maenchen-Helfen, p274.

4) Priscus fr.10, from Grodon, pse.

s) Maenchen-Helfen, p10.

6) Ammianus XXXI.,2,2.

7) Maenchen-Helfen, p3ff.

8) Thompson' p41-43.

9) Ibid.

lo) Maenchen-Helfen. p13.

11) Ammianus XXXI.,2,3.

12) Maenchen-Helfen, p15. There is no direct proof that thw Huns did this, but it was a technique known to the Tatars of the Goldan Horde, and it is likely that it was a common steppe practice.

13) Maenchen-Helfen, p170ff.

14) Maenchen-Helfen, p172ff.

15) Colin NcEveay, pl6.

16) Maenchen-Helfen, plSefr. Froa &unianus XXXI2.7.

17) Ammianus, XXXI.,2,7.

18) See E.H. Carr's What is History?

19) Maenchen-Helfen, plO.

20) St. Jerooe; source: Ferrill, p91.

21) Maenchen-Helfen, p215.

22) Ammianus XXXI., 3, 5-8.

23) Maenchen-Helfen, p30ff.

24) Priscus. fr 8., from Gordon, p7s. See also Maenchen-Helfen, footnote 92, p215.

25) Priscus, fr 8., p81.

26) Maenchen-Helfen. p136.

27) Priscus fr.2., Gordon p63. See also Maenchen-Helfen, p110 for a discussion on this subject.

2s) Maenchen-Helfen, pi16ff.

29) Priscus, fr.lb., from Gordon, p63ff.

30) Maenchen-Helfen translation, p201; from Ammianus XXXI, 2,8. See also Rolfe and Ferrill for variation of the same text.

31) Rolfe renders the opening sentence as "Et pugnant non numquam lacessiti, ineuntes proelia cuneatim...." Maenchen-Helfen claims the latin should read as "...lacessiti sed ineuntes proelia cuneatim...". In either case, the formation used as a formed body is cuneatim - wedge.

32) Maenchen-Helfen, p221. The quote is from Procopius I, 1.14 - NN's reference.

33) Maenchen-Helfen, p222ff.

34) Maenchen-Helfen, p11.

35) Ammianus, XXXI.,2,6.

36) Maenchen-Helfen, p204, quoting Vegetius.

37) Maenchen-Helfen, p242. From Frazer 1965, I, 4.

38) Maenchen-Helfen, p254.

39) Ferrill, p142ff. The argument is as follows: 42,400 sq.Ku. of pastures comprising the Plains will support 150,000 grazing borses. On a ratio of 10 horses to support 1 campaigning cavalryman, we get the figure of 15,000 horsemen.

40) Thompson. p50.

41) Maenchen-Helfen, p213.

42) See Simon MacDowall's article in Slingshots 119.14, 120.17 and 121.18 for a good description of the protagonists and the battle. Ferrill also briefly describes it (p148), as does Barker (p55).

43) Maenchen-Helfen p123ff. The campaign of the 440's.

Bibliography

Ammianus Marcellinus. Translated by J.C. Rolfe. Loab.

The Armies and Enemies of Imperial Rome. Phil Barker. WRG 4th ed.

The Fall of the Roman Empire - A Military Explanation. A. Ferrill Thaames and Hudson.

The Age of Attila. C.D. Gordon. Ann Arbor Paperbacks

The Penguin Atlas of Medievel History. Colin McEvedy. Penguin

The World of the Huns. J. Otto Maenchen-Helfen. University of California Press 1973.

A History of Attila and the Huns. A.E. Tbompson. OUP 1975 reprint.

Warfare in the Classical World. John Warry. Landsdowne Press 1980

More Huns

-

The Huns Part 1: Introduction, Sources, At War

The Huns Part 1: On Campaign

The Huns Part 2: Fortifications and Sieges

The Huns Part 2: In Battle

The Huns Part 3: Equipment and Wargaming

The Huns Part 3: Battle of Naissus

The Huns Part 3: Wargaming Campaign

Back to Saga #51 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com