1.1 Introduction

For over seventy years the Huns terrorised Europe and the Near East, extorting gold and silver from nations and engaging in frequent and bloody warfare, until their empire finally broke up in the 450's and their brief but violent impact on Europe ended. However, even after this, Huns were serving the Byzantines as effective mercenaries, and the white Huns were making their presence felt in the Middle East and in Northern India.

This article sets out to examine Hunnic warfare during this period. It discusses sources, briefly examines the level of society and technology at which the Huns existed, and looks at their campaign strategies and battlefield tactics. I will relate these findings to the wargame table, and illustrate them with a battle report. Finally, I have set up a campaign senario for consideration.

Before I begin, I muat apologise for tbe 1iaited scope of this artlele, as it only covers the European Huns. The white Huns, a Mongolian Tribe which migrated from the Altai region, and later became known as the Avars in the west, will not be considered. My main reason for this is the time I have available is limited, and most of the material I have relates to the Huns in Europe and Asia Hinor.

1.2 Sources of Interpretations

Before discussing Hunnic warfare in detail, it is neceasary to make a few comments about ancient sources. The Huns had no written language of their own, and left behind little archeological evidence of their society and lives. Thus we are forced to view the Huns through the eyes of people who had a written language and had contact with them.

Unfortunately, these were also the Huns' enemies; people who vere not disposed to write politely about a nation that routinely sacked their lands, defeated their armies in battle, and enslaved their fellow citizens. It is not surprising then, that we find the Huns referred to by Roman authors with a degree of loathing and hatred. In the Romans' eyes, the Huns "live in the form of humans but vith the savagery of beasts." (1)

To complicate matters further, details of the Huns were not always derived first-hand from Roman observers. Instead, information often arctved second hand via people such as the Goths who had usually been roughly I treated by the Huns, and forced to seek safety within the Roman empire. Thus we have a further layer of observers stamping their own interpretations and embellishments on events.

The sudden arrival of the Huns in Europe also causec oroblems. Their customs and languages were unknown in Europe, and lead to further misinterpretation. This a problem when trying to discern the inner fabric of Hunnic society.

Thus most observations are superficial - e.g. appearance, dress, overt habits. There is a tendency to stereotype and/or identify tne Huns with tribes known to ancient writers. This is why Huns are often referred to as Scythians, which became a generic name for all nomadic nations. To Priscus, Huns were Scythians; but note that all Scythians were not Huns. Ammianus however, always refered to the Huns as Huns.

An example of misinterpretation can be seen in the recording of the custom of slashing the cheeks of Hun males, a facial feature which marks out the Hun. It has been variously described as a practice applied to babies to prevent the growth of a beard, to help endure wounds, or to render the warrior ugly and more terrifying. In fact, it is a mark of mourning. On Attila's death, "they cut off part of their hair and disfigured their faces horribly with deep wounds so that the distinguished warrior might be bewailed, not with feminine lamentations and tears, but with manly blood"(2). Apparently this custom is not uncommon among some tribal societies." (3)

One of the first attributes that most authors describe is the physical appearance of a Hun. The description is designed to make the Hun appear sub-human - a creature more animal that human. Priscus and Ammianus both do this. According to Priscus, "they put to flight (the Alans) by the terror of their looks, inspiring them with no little horror by their awful aspect and their horrible swarthy appearance. They have a sort of shapeless lump, if I may say so, not a face, and pinholes rather than eyes." (4) I doubt if the Alans, who themselves have a savage reputation, would rout on seeing an ugly face.

Ammianus hated all barbarians, but the Huns were the worst (5). Unlike the Germans who had, in Roman eyes, acquired a modicum of civilisation, the Huns were primeval savages. They were faceless and sub human - they were "so monstrously ugly and misshapen, that one ought take them for two-legged beasts or for the stumps, rough-hewn into images, that are used in putting sides to bridges." (6) Even the compliments fitted this image - they had compact, strong limbs and strong necks.

There was also a widespread belief, especially around the late fourth century, that the Antichrist was born, and the end of the world was approaching. (7) The Huns rode with the devil, and the fire and destruction they wrought on the Romans and Germans added to this belief.

The belief in the primitiveness of the Huns, the hatred of them, the identification of the Huns with Armageddon, were elements that combined together to discourage ancient authors from further researching Hunnic society. At best they might equate them with an earlier tribe, at worst with supernatural events. The attitude of ancient authors has by and large filtered through to modern writers. The Huns are often presented as warlike yet primitive; in fact so primitive that they belong to the "lower stage of pastoralism." (8)

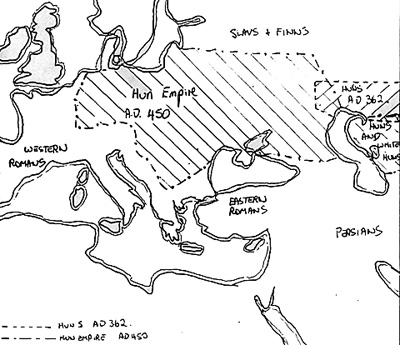

A clue that points to the incorrectness of this assumpt on is the success of the Huns in warfare. The open, hard, steppe life engenders a hardy and savage warrior, certainly. But a ferocious individual does not guarantee military success on the battlefield, nor on campaign. There are plenty of "barbarian" nations whose warriors were acclaimed for their bravery and fearlessness, yet were defeated in the field. The Huns were successful--acquiring and holding an empire (see Map 1 at right).

A clue that points to the incorrectness of this assumpt on is the success of the Huns in warfare. The open, hard, steppe life engenders a hardy and savage warrior, certainly. But a ferocious individual does not guarantee military success on the battlefield, nor on campaign. There are plenty of "barbarian" nations whose warriors were acclaimed for their bravery and fearlessness, yet were defeated in the field. The Huns were successful--acquiring and holding an empire (see Map 1 at right).

1.3 Hunnic Society and Technology

It is important to examine the social and technological level of Hunnic society, because this reflects upon their ability to conduct warfare. Modern authors, reading ancient sources too literally, equip Huns with bone arrowheads and bartered swords and spears. They live an entirely nomadic life, without a hereditary aristocracy; "The production methods available to the Huns were primitive beyond what is now easy to imagine" (9), with a correspondingly crude social structure. A howling hoard of marauders and plunderers, without military organisation, incapable of attacking fortifications or defences. Their success is attributed to pressure of numbers and/or Roman decay.

This picture of the Huns is incorrect. A detailed analysis of Hunnic society is beyond the acope of this article; besides which, authors such as Maenchen-Helfen have produced excellent works on this subject. The points I will cover relate specifically to Hunnic military matters.

An important consideration is metal working. The Huns are often described as incapable of working metals. This is incorrect. The Huns cast metal cooking cauldrons, which were usually made of copper. The technically inferior castings, and the poor quality of materials, indicate that they are not Roman workings or recast Roman bronze. The finds of tanged Hun arrowheads are all made of iron (10).

No doubt captured weapons would be used, as would bartered arms. However, to assume the entire Hun nation equipped itself with such weapons is not justified.

Ammianus claims that the Huns did not even understand how to cook food. The cooking cauldrons found, used to cook mutton and suchlike, refute this. The consumption of "half-raw flesh of any kind of animal," which they would "place between their thighs and the backs of their horses, and thus warm it a little" (11) could be a misinterpretation of a practice of placing thin strips of meat wrapped in cloth under the saddle before long journeys. When riding hard, the meat was accessible and eaten at they rode (12). The Huns indeed may have eaten raw meat and raw vegetables, but as a speciality dish rather than through any inability to cook.

It is known that the Huns possessed wagons, which call for specialist skills - cartwights. Thus we have evidence of specialisation of labour within the society. Not everyone can cast metal, construct wagons, or make weapons - especially the highly sophisticated Hunnic war bow. Specialisation requires a social and economic sturcture that has developed to a reasonable degree -- certainly enough to make a living out of specialisation.

The Huns lived a nomadic lifestyle, with animal husbandry as their economic mainstay, and hunting and fishing as supplementary occupations. However the nomadic life was not truly nomadic in the sense that they forever moved from place to place in a random procession, as the Beduins did. Rather they moved seasonally from a summer pasture to winter quarters. The summer pastures might vary, but the winter quarters always remained the same (13). They tended all kinds of domestic animals includinq cattle and sheep. The sheep provided mutton, milk and cheese, leather and felt, as well as wool which was spun. They also produced linen. There is some evidence of Hunalc agriculture (14).

I point out these domestic sKlll because they are sometimes denied of Huns. One reason for this could be during times of warfare and migration the Huns lived-on their livestock; which would typically be the situation when the Germans and Romans had contact with the Huns. At such times the nomadic pattern, wnlch lnevltable precludes industry, would be seen as normal to outside observers. And once the Huns made themselves masters of other settled tribes as happened in Europe, how much easier to be the enslaved population to produce food for the masters, rather than the masters do it for themselves.

Once we divest ourselves of the prejudice that the Huns were primitive the extreme; a society at a much lower socio-economlc level that the other nations they had contact with in the barbaricum, we are in a much stronger position to evaluate them. We need not attributing success to luck Roman military lneptltude. I believe it took more than just luck to defeat the Ostrogoths - for "In three years they had obliterated a century of German expansion" (15). The Huns did not fight with a primitive yet sly instinct. They fought witn skill and capability, from within a society and using a technology that effectively supported warfare.

1.4 The Huns at War

Having established that the Huns were not a nation that lived in the Stone Age, we are ready to look at detail at thelr military capabilities.

1.4.1 Command and Control

It has been suggested that the Huns had no form of nobility or social ordering, apart from a "disorderly government". The evidence does not support this (16).

To plan a mayor campaign such as the Huns undertook in Italy and France in the 450's takes organization and skills which cannot simply be attributed tntlrely to Attlla. Attila, who incidentally was of noble birth, certalaly would have decided upon the main thrust of his campaign, the direction, duration and aim. However, to assemble far flung tribes, arrange food and transportation for the army, to march an army through unknown lands, and conduct major sieges (e.g. Aquilla in 452) all require more than the presence of one "great man".

Other activities, such as assembling troops at short notice, performing strateglc manoeuvrers (as against the Goths in 375), and keeping troops in check once they had been paid off by their Roman paymasters (e.g. Bauto's troops in 384) all speak of a good degree of leadership and authority right own to the local tribal and sub-tribal level. Whenever the Huns fought for the Romans they fought well, and kept exemplary discipline. I am referring here to Huns hired as auxiliaries, officered by their own native leaders and not by Romans.

The Hun leaders also seemed to posses a good intelligence network. They were well aware of what was going on in the frontier Roman provinces; and were careful to conduct raids at times when Roman field armies were elsewnere.

The Huns are described as "In truces they are faithless and unreliable, strongly inclined to sway to the motion of every breeze of new hope" (17), but this was not the case. Thompson came up with a plausible explanation a treaty made with one tribe would be binding for that tribe, but would be totally irrelevant to the neighbouring tribes.

When the Huns first came into contact with the Romans, there was no Hun strong enough to enforce his will on all tribes, to prevent Hun groups from waging their own wars and making thelr own peace; conducting and breaking alliances at their, not a king's, pleasure. However, even at this early stage, concerted action on a large scale was possible - one example being the great raid into Asia in 395. Not even Attila, at the height of his power, ruled all the Hun tribes.

Over time, there was a gradual but growing concentration of power in the hands of fewer leaders, cumulating in the reign of Attila and his brother Bleda. Finally, after Bleda's murder, power was consolidated in Attilas' hands.

1.4.2 Attila

It seems appropriate at this point to consider the impact of Attila on the Hunnic nation. Some historians overstate his impact, others minimise his influence. The "Great Man" theorists of history (18) attribute the burst of energy and glory that occurred within the Hunnic nation during the 440's entirely to Attila's presence. Without Attila, the Huns would have remained a powerful band of robbers preying on the Roman border provinces, but nothing more. The opposite view holds that Attila was simply lucky to be around at the time. Other circumstances generated the Huns rise to power decline in Roman military power, the growing strength and centralisation of Hunnic power, etc.. Attila merely rode the crest of the historical wave of progress.

The truth, I believe, lies somewhere in between these two extremes. Various important pre-requisites with Hunnic society had already been developing - an effective warrior tradition, strong local leadership, a conquered and (temporarLly) subdued interior, plenty of land, an enslaved population that could attend to domestic and agricultural tasks, and a military capatility that permitted extensive and far reaching raids and campaigning. Attila's achievement was to effectively harness and exploit all the elements that existed with Hunnic society, and tO forge the loose social bonding between bites into a nation; to channel the energies in one direction: against the Roman empire.

Even at its height, the Hunnic empire was never a real danger to the survival of the Romans. Why? Attila never wished to take and rule Constantinople or Rome, nor is it likely that he would have succeeded if he had attempted it. The Huns relationship with the Romans vas parasitic they wanted the tribute and the spoils of war - booty, slaves, weapons. To rthrow the Roman empires would have been counter-productive to these requirements.

More Huns

-

The Huns Part 1: Introduction, Sources, At War

The Huns Part 1: On Campaign

The Huns Part 2: Fortifications and Sieges

The Huns Part 2: In Battle

The Huns Part 3: Equipment and Wargaming

The Huns Part 3: Battle of Naissus

The Huns Part 3: Wargaming Campaign

Back to Saga #49 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com