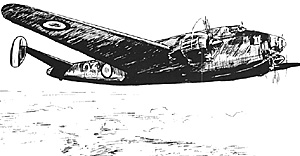

At right, LeO 451

At right, LeO 451

At 4:30 on the morning of May 10, 1940, the Luftwaffe struck simultaneously at 52 airfields in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The tiny air forces of the latter two nations were no match for Goering's armada, but both countries had had the foresight to disperse their warplanes to secret airfields just prior to the outbreak of combat. Even so, fully one-half of the Belgian planes were destroyed by the initial attacks, and the rest followed within a few days. The better-hidden Dutch airplanes were not so vulnerable to bombs but were decimated by German strafing attacks in just a few hours. Neither country presented any effective opposition to the enemy in the air.

The French response to the air attack was very sluggish, due to an abysmal command structure and the handling of air power as an extension of the army, rather than having a truly separate air force. For example, the French northern air zone was assigned 275 fighter planes (Morane 406's and Curtiss-Hawk 75A's), 15 day bombers, and 55 night bombers. But any application for air support from theseunits had to go through Vuillem in's headquarters for approval, while orders for Barratt's AASF units came from the Chief of the French Imperial General Staff.

By the time a request finally was granted, it was usually too late for the assigned units to do any good. Nor did the French expect the "sitzkrieg" to heat up so soon; air commanders had been told that no bombing was likely to take place before May of 1941. As a result, a French bomber squadron returning from a leaflet raid on Duesseldorf on May 8 spotted a German troop column approaching the French border, but took no action against it.

Those Allied airplanes that did take to the air on the tenth of May might as well have stayed home. 32 Battle bombers of the AASF attacked German columns, but for no effect. This raid resulted in the loss of 13 bombers, while all the rest sustained damage. The absence of Allied air reconnaissance over the Ardennes Forest, through which enemy forces were pouring, created a serious gap in Allied intelligence about the invasion. However, the Luftwaffe also experienced some confusion with their operations.

The German town of Freiburg accidentally was bombed by three He-111's on the tenth of May. Hitler blamed the attack first on French bombers, then on British bombers, and later exploited the error as an excuse for terror air raid reprisals against civilian targets in Allied countries. Yet bomb fragments found in Freiburg clearly identified the offenders as German.

May 11 saw only slightly more organized air resistance offered by the defenders. The last remaining Belgian bomber squadron (12 planes) attacked a bridge at Vroenhoven, but lost all but one aircraft without taking out its objective. An entire fighter squadron sent along on the raid was destroyed either in the air or when the planes landed to refuel. Luftwaffe bombers wiped out a complete squadron of Blenheims as they attempted to take off from a French airfield.

The only organized air raid on May 11 was a combined British and French effort directed at bridges over the Albert Canal and near Maastricht in Belgium and the Netherlands. However, this assault was broken up by German antiaircraft fire and the bridges were not touched by Allied bombs.

There was one bright light in the Allied air record on the third day of the war, when the French Second Army's fighter group intercepted German bombers near Sedan. Thirty bombers were shot down without loss to the interceptors. RAF Fighter Command bolstered the continental air defenses by dispatching another four squadrons of Hurricanes (64 aircraft) to France, with two further squadrons sent the following day. This left 41 fighter squadrons in Great Britain; the stripping of the island's air defenses was beginning to cause concern for Air Marshall Dowding, head of Fighter Command. Offensive air operations on May 12 were as fruitless as before, with all five Battles sent to bomb the two bridges over the Albert Canal at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt being destroyed for nought.

It was not until May 14 that a major air raid was launched by the Allies. For two hours a French force of Morane and Potez aircraft blasted away at bridges over the Meuse River, while all the remaining British Battles and Blenheims struck at the enemy bridgehead at Sedan. Again the results achieved were minimal, and again the attacking air flotillas were slaughtered. 35 of the 60 British planes involved were shot down, along with at least 40 French machines.

Although the total strength of the AASF was raised to 250 aircraft on May 14, few bombers remained serviceable by the end of the day. British air losses for this day alone totalled 67, and only 206 of the original 474 British planes in France were left after just five days of fighting. French aircraft losses were comparable to the 57% attrition rate suffered by the AASF. In desperation, French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud pleaded with Winston Churchill for an additional ten squadrons of Hurricanes, but Dowding, concerned over the alarming rate of loss, stifled this request at a meeting of the War Cabinet on May 15. However, the next day the War Cabinet partially reversed its decision and sent four squadrons (actually eight half squadrons) to France.

That same day, Churchill requested that the other six squadrons be sent. Due to Dowding's opposition and limited space available at the British airfields in France, the War Cabinet decided to send the six squadrons on a rotational basis - three would operate from France in the mornings and then return to southern England while the other three would operate from France in the afternoons. That way, only three of the six squadrons would be risked at any one time.

The overwhelming losses suffered by the AASF bombing force during the first week of the war convinced Barratt that his Battle light bombers (which were nearly as obsolete as the French Amiot 143 bombers) were not suited for combat when unescorted by fighters. On May 15 he withdrew the remaining Battles from day combat in France. Four months later, Goering would arrive at a similar conclusion and action regarding the use of Stuka dive bombers in the Battle of Britain.

May 16 was another gloomy day for the Allies, as 36 of 67 British fighters sent into action near Sedan were destroyed. British bombing efforts at this stage focussed on strategic bombing of the Ruhr, Germany's industrial heartland, but this approach had little positive impact on the Allied war effort. The lack of air support of Allied ground operations was in stark contrast to the close coordination of Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht, and this lack seriously hampered the Allied defense. Many opportunities to bomb the Germans in their compact formations on the roads were missed by those French and British planes that were in the air. The French air inferiority so demoralized the ground troops who were subjected to incessant dive bombing attacks that it was said that, "When there are three planes, then they are French. When there are forty, they are German."

More French Air Force in World War II

-

Introduction

Preparation for War

The Machines

The First Week

The Beginning of the End

To The Armistice, 1941-1945

Back to Grenadier Number 12 Table of Contents

Back to Grenadier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by Pacific Rim Publishing

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com