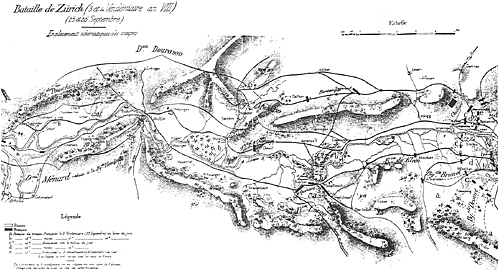

The battlefield of Zurich is dominated in the east by

the city itself, a typical Vauban type fortress. Running from

south to north through the center is the River Limmat,

which empties into Lake Zurich on the southern edge of city

of the same name. North of Zurich, the River Limmat splits,

with a smaller tributary, the River Sihl, running directly

south and skirting the western edge of the fortress walls. At

this same point the Limmat turns abruptly west and flows

some 18 miles where it joins the Aare River near the city of Brugg.

The battlefield of Zurich is dominated in the east by

the city itself, a typical Vauban type fortress. Running from

south to north through the center is the River Limmat,

which empties into Lake Zurich on the southern edge of city

of the same name. North of Zurich, the River Limmat splits,

with a smaller tributary, the River Sihl, running directly

south and skirting the western edge of the fortress walls. At

this same point the Limmat turns abruptly west and flows

some 18 miles where it joins the Aare River near the city of Brugg.

The river's width was normally about 70 to 80 yards. The entire area was covered of low plateaus, each about 20 yards higher than the river itself, with the most prominent of these being the Albis which overlooked Zurich from the SW. Between the Albis and the Sihl was the only reasonably flat piece of real estate in the area, the Sihlfeld. The area was dotted by clumps of trees and small villages built of sturdy masonry and wood construction.

On the morning of the 25th of September, 1799, the Russian forces of Generalanchef Rimskii-Korsakov were deployed as follows. LTG Prince Gortchakov commanded a force 9,773 men and 16 guns, most of which were stationed on the Sihlfeld facing west. Other portions of this force included MG Essen's command of 2,237 which occupied the area between Lake Zurich and the Sihl, the garrison of the city (one grenadier battalion, Ekaterinoslav Regiment) and four squadrons of the St Petersburg Dragoons at the small town of Wipkingen to the NW of Zurich. All Russian parks and baggage trains remained in Zurich.

Deployed along the north bank of the Limmat, over a distance of some eight leagues, was LTG Dourasov's "division" of 7840 men and 16 guns. From the small village of Hongg to the town of Baden stood MG Markov's brigade, while from Baden to Koblentz, where the Limmat met the Aare, stood MG Poustchschin's brigade. Some 92 vedettes were deployed to provide early warning.

There was also a reserve formation under LTG Sacken, some 5,670 men organized in four musketeer regiments plus artillery. Most of these troops, however, had been released to reinforce Freiherr von Hotze's Austrian contingent which stood directly south of Lake Zurich along the Linthe River. East of Zurich, near the Upper Rhine stood a cavalry reserve under the orders of MG Goudovitch. It consisted of 3.276 sabres along with 28 pieces of artillery.

British LTG John Ramsey, who tagged along to insure that His Britannic Majesty got his money's worth, was appalled at the lack of security on the part of the Russians. He wrote that Korsakov was not:

aware of the necessity of those precautions which other armies adopt in particular circumstances, and which he will in all probability feel inclined to attend to, when more acquainted with the stratagems of an active and clever enemy who acts scientifically and with system. The same deficiency appears evidently general among the officers, from the manner in which service is carried, and particularly that of the advanced posts, where we have seen the troops with their baggage and baggage wagons as if in perfect security.

The pickets of Cossacks, notwithstanding the

reputation they have for this species of service,

having their horses unsaddled and at grass, within

pistol-shot of the enemy's vedettes. [13]

Considering the plans of General Massena, such an

observation was evidence of impending disaster. French

plans envisioned a dawn attack on the center of Markov's

brigade at the small village of Dietikon, where the Limmat

formed a semicircle about a mile wide. To the north of the

river stood an imposing plateau some 20 yards higher than

the river, and before it was a 300 yard wide field filled with

thick bushes. The plateau was manned by only a single

grenadier battalion and a lone Cossack regiment. A thick

forest bordered the southern bank of the Limmat at this

point.

While all bridges had been blown across the river,

Massena felt he had adequate engineer support to force a

crossing.

In a letter to the French Directory Massena laid out

the specifics of his plans. He wrote:

I have the honor to advise you that, on 3

Vendemiaire, I shall cross the Limmat at Dietikon

where I shall be in person, while General Soult

crosses the Linthe between the Lakes Wallenstadt

and Zurich and while General Menard makes a

false attack at Brugg. This latter shall effect a

passage, but it will be secondary to the crossing at

Dietikon. General Lecourbe shall at the same time

march on Reichenau and menace Coire.

The length of the line which the army shall

observe, or hold the enemy is so large that I am

unable to assemble at the principle crossing but

14,000 men, on the Linthe under Soult there are

7,000 men, and Brugg 4,000, and before Zurich

there are 6,000, assigned to stop all who might

pass that way during my crossing...

General Lecourbe has sent me emissaries who

advised him of Souvorov's arrival in Bellinzona

with a corps of from some 15,000 to 18,000 men.

Efforts are being made to verify these reports. But

I have already been advised that an enemy corps

detached from the Army of Italy is already on my

right. [14]

The concerns about Suvorov notwithstanding,

Massena decided to proceed with his plans. The force that

would make the diversionary attack on the extreme right of

the Russian army was General Menard's 6th Division,

consisting of only a single infantry brigade plus some

pontooneers and the 23rd Chasseur a Cheval Regiment.

The diversionary attack to be made on Zurich, which

constituted the extreme left of the Russian army, was

entrusted to General Mortier's 4th Division which consisted

of Brigadier Drouet's and Brunet's brigades. Massena

hoped that these two forces would make enough

commotion to draw all available enemy forces away from the

main assault point at Dietikon.

The crossing at Dietikon was to be handled by

General Lorge's reinforced 5th Division, consisting of

Brigadier Gazan's and Bontemp's brigades, as well as

Brigadier Quetard's brigade from the 6th Division. Four

companies of pontooneers would assist Lorge in

completing the crossing. A reserve force of 6,327 troops

was stationed near the town of Altstetten under the

command of General Klein.

It counted two battalions of converged grenadiers,

the 102nd Ligne Demibrigade as well as two horse artillery

batteries and four regiments of cavalry. Altstetten

overlooked Zurich to the east, but Klein could easily march

in any direction

and was in fact given orders to be prepared to follow Lorge

across the Limmat.

Once the northern bank of the Limmat had been

secured (and the Russian line of battle effectively split),

Massena planed to wheel his troops to the east and march

directly on Zurich via two routes through the towns of

Regensdorf and Wipkingen. If successful, the enemy lines

of communication to the north of Zurich would be

irreparably cut. Assuming that Soult had succeeded in his

mission to cross the Linthe and destroy von Hotze, Zurich,

and the Russian army it contained, could well become

totally encircled. The plans looked sound, the troops were

eager, so at dawn on the 25th of September, the first boats

were launched and every French cannon in the area fired.

At 0400 hours, BG Gazan crossed the Limmat in

several small boats with his advanced guard, covered by a

hail of artillery fire. His forces consisted of three carabinier

companies of the I Oth Legere Demi-brigade, a full battalion

of the 10th and three companies of the 37th Ligne Demi-

brigade. These troops soon dispersed the small number of

Russians posted along the northern bank, splattering them

north towards the plateau near Klosterfahr. The actual

crossing took no more than three minutes and soon the

boats were sent back to pick up a second wave of assault

troops.

By 0500 hours the northern bank was secure enough

for the pontooneers to begin the construction of a

permanent bridge.

Gazan's advanced guard did not halt after securing

the northern bank, however. Instead they pushed up the

steep plateau where they encountered Col Treublut's

Converged Grenadier Battalion and a few reinforcing

infantry companies. The Russians were soon sent packing

under the heavy French assault and by 0600 the plateau

was under their complete control. During this assault, the

Russian brigade commander, MG Markov, was grievously

wounded and captured.

By 0730 hours, the pontoon bridge across the Limmat

was complete and by 0900 hours all of Lorge's 5th Division

was across and ready to march. Massena's Chief of Staff,

General Oudinot, took control and immediately swung the

division to the east. Two brigades, supported by most of

the division's artillery and cavalry, would march straight for

Zurich via the Engstringen-Hongg road. A third brigade

would march for the same destination via a more northern

route, traveling down the Dalikon-Regensdorf Road. Two

infantry battalions would swing west and occupy the town

of Wurenlos to provide early warning of any Russian

troops moving from that direction. Massena needn't have

worried.

Simultaneous with Lorge's attack across the Limmat,

General Menard's 6th Division made an immediate crossing

of the same river near the small town of Vogelsang. This

action not only drew the attention of the local Russian

brigade commander, but that of his boss, LTG Dourasov, as

well. Mesmerized by Menard's feint and somehow thinking

that upon his shoulders rested the entire fate of the Russian

Empire, Dourasov grabbed every available Russian soldier

in the area and threw them at Menard's single brigade of

infantry. Dourasov not once thought to contact Markov's

brigade to learn of anything that might be happening to his

east.

Not once did he send out a single reconnaissance

party to the east to insure an adequate intelligence flow

from the rest of his command. As a result, his tough

Russian troops fought Menard to a standstill, completely

oblivious to the disaster befalling the Russian army at

Zurich. It was not until 1900 hours, when a lone Cossack

officer finally made at through with an official report, that

Dourasov realize his incredible error. In open mouth

disbelief he ordered his 3 1/2 battalions and 10 squadrons

to withdraw towards Regansdorf (by this time in French

hands). Upon learning that movement to this village was

not possible, he ordered a retreat to the north, crossing the

Rhine on the night of the 26th and 27th of September.

Mortier's attack on the main concentration of

Russians before Zurich had also gone well. His troops had taken up arms at the break of dawn and had moved out from

the Albis heights at 0700 hours to attack the tiny town of

Wollishofen, defended by two musketeer battalions and a

battalion of the Ekaterinoslav Grenadiers. Prince

Gortchakov heard the commotion and immediately

reinforced the town with a battalion each of musketeers and Jaegers.

Stopped Cold

This stopped the French attack cold, so much so that at

1000 hours the Russians ordered a general advance across

the Sihlfeld plain, pushing Mortier's troops to the base of

the Albis heights.

Here, however, the Russians found Swiss terrain and

French tactical doctrine to be a much tougher proposition

than previously expected. Skirmishers and light artillery

ripped into the Russian formations, causing serious

casualties. One eye witness noted, "Whole files collapsed

forwards, and entire ranks were struck down in enfilade.

The Russians trampled their dying comrades underfoot

so as to close up in good order and reload by platoons and

divisions." Another eyewitness recounted, "the hedges

and vineyards all about the village were full of wounded

and dying Russians, though I do not recollect seeing five

dead Frenchmen on the whole ground. This is easily

accounted for from the nature of the country, which is

particularly well calculated for the French manner of

fighting." [15]

Massena nevertheless ordered portions of Klein's

reserve division to reinforce Mortier, and together they

repulsed three major Russian attacks. Korsakov was on the

scene, though he originally had gone off in the direction of

Lorge's crossing of the Limmat at about seven that

morning. Convinced that the noise he heard was little more

than a diversion, he returned to the fighting at the Sihlfeld

plain at 0730 hours.

He also took the precaution of recalling those

battalions of Sacken's Reserve that were on their way to

reinforce the Austrians along the Linthe. Now at 12 noon,

he saw no reason for further fighting and ordered his

Russians to fall back to their original position in front of

Zurich.

Meanwhile, the advance brigades of Lorge's division

had moved smartly eastward and had cleared Hongg by

about 10 in the morning. LTG Sacken, his own troops

countermarching back to Zurich, was essentially without a

job and happened to pass by the French advance. He

watched in abject horror at what seemed to be thousands

of French infantry pouring over the heights near Hongg.

He grabbed every available soldier in the area and begged

Korsakov for immediate help, but received only LTC

Granovski at the head of three companies of the

Ekaterinoslav Grenadiers. These troops were not enough to

stem the French tide, however, and Sacken's few troops fell

back to Wipkingen.

Sacken continued to send courier after courier to

Korsakov to advise him of the threat and request additional

troops, but never received a reply. Since there were no

couriers left, he sent off his British liaison officer to

describe the situation to Korsakov. No help arrived from

Korsakov, but shortly thereafter a Bavarian regimental

commander strolled into the area at the head of some

promised reinforcements from that tiny Germany state.

Sacken exclaimed, "You have arrived at the right

moment. I do not know where to find my commanding

general and ask that you do not lose precious time seeking

him. Occupy that height with your brave troops and you

shall render me an invaluable service. You cannot present

yourself in a better fashion to your new commander in

chief."

The Bavarian colonel looked over the battlefield,

quickly sized up the situation, politely declined Sacken's

request and left the area with his regiment in tow, never to

be heard from again.

[16]

At 1400 hours, Col Garin arrived with seven companies

of Russian grenadiers to reinforce Sacken. This force only

delayed the inevitable. Overwhelmed in front, being flanked

in the north by French troops marching from Regensdorf,

and taking canister from French guns across the Limmat,

the Russians could not stand. At the same time, Korsakov

realized his mistake and ordered a general withdrawal into

the city of Zurich by all Russian forces.

This movement was completed by evening under

heavy pressure from the French. During this time the only

assistance received by Korsakov was the Staroskol

Musketeer Regiment, part of Sacken's returning reserve.

They assisted their commander in his retreat into the city.

He, himself, was on foot as his horse had been shot out

from under him. Several bystanders also noticed several

musket ball holes in his coat. Many of his regiments were in

even worse shape. One Russian musketeer Regiment had

barely 200 men left under arms.

[17]

That evening Korsakov called a council of war and

decided to request terms from the "obliging" General

Massena. He requested only the terms appropriate for an

18th century army who had fought bravely in defense of a

major fortress. Korsakov would freely open the city so long

as his troops could march away, carrying their weapons,

baggage and wounded with them. Doughty Andre

Massena said "no."

Alpine Thunder The Battle of Zurich 1799

Introduction

The War of the Second Coalition

The Commanders

Fire in the Mountains

Epilogue

Order of Battle

Jumbo Map of Battle of Zurich: Sep 24-25, 1799 (monstrously slow: 716K)

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 4

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com