At this point one must necessarily shift away from

the battle and turn to an examination of the commanders

involved. In one of the strangest incidents in all military

history, their greatly differing perceptions about the very

nature of war would allow one an advantage that would

almost insure victory. The victim can not be blamed,

however, for he merely acted in a way in which his society

had acknowledged as correct and proper.

At this point one must necessarily shift away from

the battle and turn to an examination of the commanders

involved. In one of the strangest incidents in all military

history, their greatly differing perceptions about the very

nature of war would allow one an advantage that would

almost insure victory. The victim can not be blamed,

however, for he merely acted in a way in which his society

had acknowledged as correct and proper.

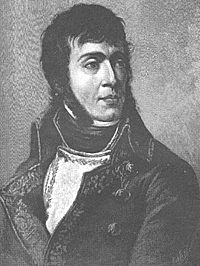

The unfortunate commander in this case was Generalanchef A.M. Rimskii-Korsakov, the Russian commander of the Allied forces in the Swiss area of operations. Korsakov was 46 years old at the time of this momentous battle, and had a relatively distinguished military career. He had begun his service to the Russian crown as a cadet in the Preobrazhinski Guard Regiment, and at the age of 25 had been named the Lieutenant Colonel Commanding of the Tchernigov Musketeer Regiment. He served with distinction against the Ottoman Turks.

In 1794, he obtained permission to accompany Allied

forces invading France, performing so well that he came to

the personal attention of Czarina Catherine the Great.

Further exemplary service against the Persians followed,

and in 1797 he was named the Inspector General of

Infantry. He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant

General in 1798, receiving his army command the next year. [5]

Korsakov's record does not betray the man as a

military dunce. Nevertheless, there were other factors

involved in his appointment by Paul 1. First, Korsakov

openly supported the Czar's military reforms and agreed

with Paul that the discipline and courage of the Russian

soldier would overcome all obstacles. But in the second

case, there was the strange consideration of music - yes,

music. Korsakov, you see, came from a very musical family,

one of its later members (Nikolai) gaining lasting fame as

the composer of "Flight of the Bumblebee." Our present

subject's contribution, however, was the composition of a

slow march for the Czar's Semenovski Guard Regiment. It is

said that Paul liked it so much that he played it over and

over again. With such distinguished credentials, it seemed

only logical to appoint Korsakov to a position of great

responsibility. [6]

It thus happened that Korsakov took both his sword

and his composer's desk to Zurich. There one eye witness

noted, "Sometimes the French musicians came to play

martial airs on the banks of the beautiful Limmat. Then the

Cossacks would spring to their feet of their own accord,

and dance and jump in circles."

The Russian Generalchef noticed the stirring music

as well, and this was to be his downfall. [7]

It is little wonder. Korsakov, like most of the Russian

officer corps, were products of a society that had at least

partially embraced the European concepts of enlightenment.

This historical era, which we know as the Age of Reason,

was born as a direct result of a political, social and

economic revolt against the chaos of the Thirty Years War.

As military activity represented one of European man's

most important endeavors, it was only natural that the Age

of Reason influence it as well. What this influence produced

was, like the society it served, a military system determined

to operate in such a manner as to keep human conflict under

strict control and in as much a state of order as was

practical. The chaos of the Thirty Years War depopulated

nations, wrecked economies and nearly destroyed

dynasties. Order in all things, to include warfare, was

needed to insure that this did not happen again.

The warfare of Korsakov was thus one of a limited

nature where the civilian population was avoided as much

as possible, so that the agrarian economies of Europe might

proceed undisturbed and the state might flourish. This

necessitated the rise of professionally trained and

disciplined armies that could subsist without the need for

contact with civilians. Such armies were small due to the

expense of maintaining them, and moved slowly due to the

amount of baggage they had to carry.

And as such military establishments represented a

considerable investment to the monarchy, they were rarely

committed unless victory was absolutely assured. It is no

wonder that France's great Marshal Maurice de Saxe wrote,

"I do not favor pitched battles, especially at the beginning

of war, and I am convinced that a skilful general could make

war all his life without being forced into one." It is also little

wonder that such thinking created a style of warfare based

on movement and position, assuring the maintenance of the

political, social and economic status quo. Order and control

had triumphed over chaos. [8]

Obviously, such military doctrine could not flourish

unless specific rules, both legal and traditional, were

created to govern its conduct - always with the idea of

maintaining control and order. Such strictures manifested

themselves in many ways, to include the still relevant Laws

of Land Warfare, and what historian Christopher Duffy

refers to as the "cult of honour."

One can name numerous examples throughout this

period of proper battlefield behavior. There is, of course,

the famous story of the British commander offering the

French Guards the honor of the first volley at Fontenoy in

1745. While that story may be pure concoction, other tales

are definitely not. The same battle, for example, saw a

French officer post a guard over a wounded English

colonel, even offering him his purse to ensure proper care.

Frederick the Great was know to have "chewed out"

one of his own Jaeger, who was wounded and lying in

ambush for the next enemy epaulet that happened to stroll

by. "Old Fritz" blasted the disgraceful fellow and demanded

that he stand up and "fight like a Prussian." Frederick

would have been pleased to know that on at least one

occasion, the French returned the favor.

Before the battle of Rosbach (1757), one French

officer reported to the Due de Crillon that the Prussian king

was within musket shot and asked for a marksman to

eliminate him. "Crillon handed his loyal Brunet a glass of

wine, and sent him back to his post, remarking that he and

his comrades had been put there to observe whether the

bridge was burning properly, and not to kill a general who

was making a reconnaissance, let alone the sacred person

of a king, which must always be held in reverence." It was a

time when fortress garrisons were normally afforded the

honors of war after a courageous defense, and where the

pursuit of a broken enemy was considered in poor form. It

was, after all, the great Frederick who responded to a

proposal for immediate pursuit with the reply, "Yes, you are

quite right, but I don't want to defeat them too badly." [9]

But if this was the military culture of Korsakov, it

most definitely was not that of General Massena. Born the

son of a poor winegrower in 1756, he enlisted in a French

light infantry battalion in 1775, rising through the ranks to

sergeant-major in 1784. He retired in 1789 and became a

most effective smuggler and merchant. He volunteered for

military service to the Republic in 1792 and his talents soon

made him a major general in 1793.

In 1798 he became the commander of the French

Army of Rome, taking the reigns of the Army of the Danube

the next year. He was the type of general who could enforce

an iron discipline, and yet plunder a province with the blink

of an eye. He hated to read, so could not plan a campaign,

but was incredibly resourceful in the face of the enemy. He

was a "general by instinct," and it was none other than the

Duke of Wellington who swore that he never slept

comfortably while Massena was in the field. In short he was

the perfect French Revolutionary general. [10]

Like Korsakov he was also a product of his culture.

But his society was one that rejected warfare as a means to

simply rearrange a few boundaries while retaining societal

order. To the young French Republic war was the legitimate

means to survival through the destruction of the absolutist

nations of Europe that threatened it. War was an instrument

by which the current political order would be overthrown

and replaced with one built on the Revolutionary tenants of

"liberty, equality and brotherhood." Only then would the

French Republic be safe. These beliefs required a type of

warfare that was designed to totally destroy the enemy. It

was a type of warfare that required generals to win big and

to win at all costs.

It accepted that nearly anything in war was legitimate,

so long as victory was the ultimate end. In the words of the

famous "Organizer of Victory," French War Minister Lazare

Nicolas Carnot,"Act in mass formation and take the

offensive. Join action with the bayonet on every occasion.

Give battle on a large and pursue the enemy until he utterly

destroyed." This was hardly the gentlemanly conduct to

which Korsakov, or any other Allied officer was

accustomed. [11]

Given such diametrically opposed views about

warfare, what happened next around the steep, rolling hills

of Zurich suddenly begins to make a little more sense.

Historian John R. Elting recalled,

There was a momentary semi-truce around the

Swiss city of Zurich in 1799. East of the Lake of Zurich

and its northern tributary, the Limmat River, an Austro-

Russian army was readying for an attack to be launched

as soon as the victorious Suvorov's army came up out

of Italy through St Gotthard Pass into the French rear.

To the west was Massena, coiling to strike first.

Meanwhile, Austrian and Russian officers tried to

amuse themselves with parties and balls, but such

affairs went limpingly for lack of proper musical

accompaniment. Austrian bandsman somehow lacked

the necessary gentletouch; as for their Russian

colleagues, it is my uncharitable guess (founded on

personal observation two and a half centuries later) that

it had proved impossible to keep them out of the

punchbowl.

From behind the French lines came the sounds of

several fine bands, tooting with skill and zest.

In the lightest spirit of eighteenth-century warfare,

the Allies requested the occasional loan of some of

those French musicians, if General Massena would be

so obliging. Dour Andrd Massena was a man who

would have opportunity into his bedroom before the

average general began to wonder if there were an

unusual noise at his front door. He obliged. If some of

the French bandsman he graciously provided

occasionally peered around the comers of their

sheet music, the Allies assumed they were simply

ogling the fair ladies swirling past them and not

noting what regimental uniforms their partners

wore. [12]

One will never know how much influence such

musical intelligence made on the thinking of "dour" Andre

Massena, but his attack on the Allies remains to this day an

achievement of planning and surprise. It was a battle

launched with perfect timing as Suvorov had not yet arrived

and most of Korsakov's Austrian allies had just departed the

area to move north towards the forces of Archduke Charles.

One can only wonder whether this was a matter of good

fortune, or whether a lack of Austrian uniforms at a military

ball became a decisive factor. Regardless, the time was now

0400 hours, 25 September 1799, and the destruction of

Korsakov's army, not to mention the concept of warfare it

represented, was close at hand.

Alpine Thunder The Battle of Zurich 1799

Introduction

The War of the Second Coalition

The Commanders

Fire in the Mountains

Epilogue

Order of Battle

Jumbo Map of Battle of Zurich: Sep 24-25, 1799 (monstrously slow: 716K)

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 4

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com