Eyewitnesses to those amazing times did not mince

words. One described the Holy Warriors of the Czar as

"exactly the same hard, stiff wooden machines which we

have reason to figure ourselves as the Russians of the

Seven Years War ... they waddled slowly forward to the tap-tap of their monotonous drums; and if they were beaten

they waddled slowly back again, without appearing in

either case to feel a sense of danger..."

Eyewitnesses to those amazing times did not mince

words. One described the Holy Warriors of the Czar as

"exactly the same hard, stiff wooden machines which we

have reason to figure ourselves as the Russians of the

Seven Years War ... they waddled slowly forward to the tap-tap of their monotonous drums; and if they were beaten

they waddled slowly back again, without appearing in

either case to feel a sense of danger..."

Yet Britain's Military Mentor also noted that "no

troops in the world are so careless of being attacked in the

flank, or turned..." Of the other warring parties Albrecht

Adam wrote in 1797, "I was roused to enthusiasm by the

smart and colorful uniforms of the French Revolutionary

army, the keen spirit, the very soul, the characteristically

wild faces of those soldiers, and their strange way of

moving. The most striking contrast was produced by the

Austrian armies. We saw them pass by, calm and grave,

mostly in serried columns, correctly dressed even in mid-campaign. Resigned to hardship, never forgetting their

discipline, they always made an impression to be

respected." [1]

Whether they knew it or not, these keen observers

had just seen irrefutable proof of one of the most important,

yet most neglected, aspects of the Napoleonic period.

Simply, it was that the French Revolutionary and

Napoleonic Wars were notjust armed conflicts between

opposing governments, they were wars between vastly

different societies as well. This in turn meant that the

soldiers, as well as the generals who commanded them,

produced by these societies varied greatly in appearance

and demeanor to all who saw them.

This betrayed the fact that they often looked at the

very nature of war itself in ways that were totally

incompatible with each other. It was not a case where one

side played by the accepted rules of the game and the other

did not. Rather it was a situation where the set of rules for

one side was completely different to the those used by the

other. Ultimately, it remained an area of armed conflict

where the human factor could still determine the difference

between victory and defeat.

Second, and perhaps of far greater importance, is that

it helps us realize that the Allied generals who fell so hard

under the hammer blows of the French, particularly in the

early career of a young upstart Corsican named Bonaparte,

were not the idiots many have made them out to be. They

were commanders who potentially could have done quite

well in the era of Frederick the Great. They were simply men

who played the game of war with rules far out of date. It

was not their fault, as no one had told them the rules had

changed.

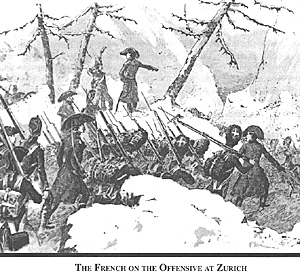

This clash between opposing military values, and the

decisive results it often produced, took many forms during

the wars of the French Revolution. But perhaps no where

can one find a more fascinating example than the lush

mountainous landscape around the picturesque Swiss

fortress of Zurich. The date was 25 September 1799, and a

battle was about to fought and decided largely on pure

human perception, to include the rather innocuous subject

of a person's taste in music.

Alpine Thunder The Battle of Zurich 1799

Understanding this concept focuses many things

into crystal clear perspective, but two should be of

particular importance to those interested in the period. The

first is that it helps explain exactly why the undisciplined

and poorly trained armies of the French Republic were able

to more than hold their own against their professional

adversaries. While differences in doctrine had much to do

with this, the influence of the human perspective can not be

discounted.

Understanding this concept focuses many things

into crystal clear perspective, but two should be of

particular importance to those interested in the period. The

first is that it helps explain exactly why the undisciplined

and poorly trained armies of the French Republic were able

to more than hold their own against their professional

adversaries. While differences in doctrine had much to do

with this, the influence of the human perspective can not be

discounted.

Introduction

The War of the Second Coalition

The Commanders

Fire in the Mountains

Epilogue

Order of Battle

Jumbo Map of Battle of Zurich: Sep 24-25, 1799 (monstrously slow: 716K)

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 4

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com