The West Africa Mission of Voulet and Chanoine

The West Africa Mission of Voulet and Chanoine

(“Apocalypse Now” in West Africa)

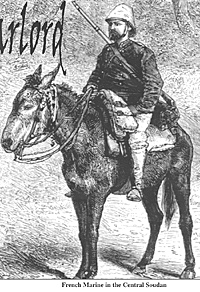

The scandal of the Voulet-Chanoine mission lay buried in secrecy and government cover-up for many years. Even before the mission, the reputations of its two leaders were known within the colonial circle. Former colleagues had described them as cruel and sadistic. During their campaign to subdue the Mossi tribes of the Wagadugu region earlier in the decade, they had left a trail of murder, mayhem and destruction. That they were then chosen for this mission despite warnings from government circles only adds to the intrigue. The mission was planned as an exploratory diplomatic mission but prepared as a large military adventure. Due to serious resource depletion in the Western Sudan from earlier campaigns, warnings of the difficulty of finding adequate numbers of porters and even potential rebellion were given but unheeded.

Although the meeting of the three Lake Chad missions had been considered in Paris at their conception, the orders given to Voulet did not mention the rendezvous. His orders were a vague instruction to bring the eastern territories of the Niger River region, and Lake Chad, under French Protection. The orders left up to Voulet what route he would use, and more poignantly, how he might conduct himself with the local population.

Driven by ambition, and the race to Lake Chad, there was “glory” to be had in arriving first and defeating Rabih.

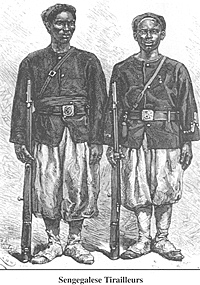

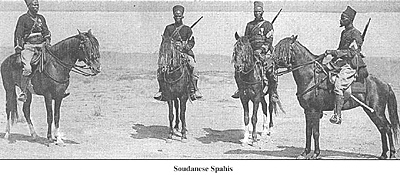

The officers of the mission under Capitaine Paul Voulet and Lieutenant Charles Chanoine were Lieutenant Paul Joalland, who commanded the artillery, Lieutenant Marc Pallier, Lieutenant Louis Peteau, and Dr. Henric. Three French NCO’s completed the European members. The regular troops consisted of 50 Senegalese Tirailleurs and 20 Spahis Soudanais. Also included were 400 locally raised auxiliaries and 30 interpreters and guides. They were all armed with Lebel rifles, the Spahis armed with Lebel carbines with a total of 180,000 rounds of ammunition. The artillery consisted of an 80mm mountain gun with 100 rounds.

Beginning

The mission began west of Timbuktu, 400 miles up the Niger at Koulikoro in November 1898. The mission split into two elements. Chanoine led the majority of Tirailleurs and the auxiliaries across land, below the Niger Bend, while Voulet traveled down the Niger, partly by canoe and partly by land. Stopping at Timbuktu, Voulet met with Lieutenant-Colonel Klobb, commander of the garrison there. The meeting was cordial and Klobb reinforced Voulet with 70 Senegalese Tirailleurs and 20 Spahis. Klobb traveled with Voulet 250 miles down the Niger before returning. Klobb noted that Voulet appeared to be a man without purpose and direction and expressed concern for the mission.

Chanoine’s trek across land was with out adequate supplies. Almost 150 of his men died from hunger or exposure, on one day April 20, 1899, sixteen died from thirst until saved by freak storm. Villages were attacked, destroyed and ravaged on the way to provide porters (who were enslaved into service) and supplies. When the two missions re-combined at Sey the situation was bleak. Lieutenant Peteau protested to Voulet, who dismissed him and sent him back to Senegal.

During the mission’s passage, rumors from French residents in the Soudan concerning the mission’s atrocities began making their way back to the coast. When Peteau returned, he confirmed the news and submitted a full report to the ministry. A cover up was ordered and Lieutenant-Colonel Klobb, on his way back to France on leave, was ordered back to take command of the mission. The ministry later admitted that it was hoped that the two renegade officers would redeem themselves by dying gloriously in battle.

The atrocities committed on the expedition were nothing short of ridiculous. One tirailleur who had shot a porter, was himself executed for wasting a bullet on the porter rather than using his bayonet: Another being executed for losing ammunition. Ordered to raid villages for porters, the tirailleurs were to execute any who would not comply and to return with the heads of those so executed as proof of compliance with the orders.

Klobb crossed the Niger Bend with Lieutenant Meynier and a platoon of 49 tirailleurs to relieve Voulet. After reorganization in Sey to reduce the expedition to the fittest and fastest men, 36 tirailleurs were left to continue the mission with a few Spahis Soudanais and 13 porters.

Desperately short of food and water, the Voulet – Chanoine mission had begun to ravage the area south east of Sey. Blaming the guides for their inability to locate a suitable village to supply them, many of them were hung. On locating a village that was attacked, two of the tirailleurs were killed. In retaliation, Voulet ordered the execution of 150 women and children.

Klobb caught up to within a few hours of Voulet, near Dankori, and sent ahead a team of 4 tirailleurs to inform Voulet that he was being relieved as head of the mission. Voulet’s reply was that he would rather die than submit to this humiliation, that he had 600 armed men and that if Klobb approached, he would treat him as an enemy. Voulet and Chanoine then separated the officers and did not inform them of Klobb’s intent. Voulet occupied the officers with a task and took those tirailleurs who remained loyal to him and prepared them to receive Klobb’s column that was approaching their rear.

Placing his men in a defensive position, Voulet was approached by Klobb and Meynier. Voulet ordered them to halt or he would fire on them. Klobb believed that Voulet was quite mad, and that neither his tirailleurs provided from Timbuktu nor the Europeans would open fire on him. However, Klobb was unaware that Chanoine had dispersed the forces in such a manner that none of the white officers or Klobb’s tirailleurs were opposing him. Voulet ordered his tirailleurs to fire two volleys into the air. Klobb was yelling for Voulet’s tirailleurs to obey his orders, Meynier was yelling for his own men not to retaliate. Voulet ordered his men at pistol point to fire on Klobb. Klobb fell dead and Meynier was wounded.

Sengegalese Tirailleurs

Voulet’s remaining tirailleurs, particularly those of Klobb’s Timbuktu command were dissatisfied with the situation and rumors of mutiny began to spread. One of the interpreters informed Voulet of the discord and was promptly shot by Voulet for not having told him sooner. This increased tensions even further and fearing an imminent mutiny, Chanoine and Voulet fired on the tirailleurs who returned fire, killing Chanoine instantly. Voulet fled with six tirailleurs who remained loyal to him. Those tirailleurs who had mutinied made there way to Sey to join the other white officers and placed themselves under their command. The next morning, Voulet approached the camp and was shot dead by the sentry. Lieutenant Pallier took command and suggested that the only way they could now save their careers was to march to Lake Chad and defeat Rabih.

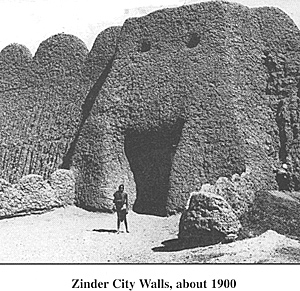

Zinder's Walls, about 1900

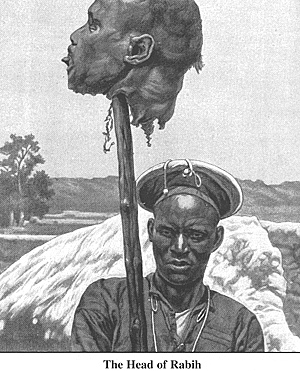

Joalland strengthened the French position in Zinder and built a fort. He also sought out the Amir of Zinder, Ahmadu, who was responsible for the killing of Cazemajou, the leader of a French mission the previous year. Finding him, he killed him and decorated the city walls with his head on a pole in the same place Cazamejou’s head had been placed. Sergeant Bouthel was appointed Commandant and left with the wives of the tirailleurs who had been accompanying the mission, as was the custom.

There was no news of Lamy at Zinder. Joalland had received new orders from Klobb (via Meynier), that a rendezvous with Lamy, although desirable, was secondary to reaching Lake Chad and bringing it into the French sphere. So on October 23 they left eastwards for the Lake. They reached the lake and traveled around its north end. They enacted treaties with several weak tribes and fought some minor engagements. One against Tubu desert raiders resulted in one tirailleur killed and six wounded.

By now, Joalland was receiving rumors that there had been two major battles involving white men from the south, one in which the whites had been annihilated (See Part 1) and the other inconclusive (See Part 2). Having arrived across the river from Gulfei, Joalland sent six men under Sergeant Abdul Saul up the Shari in an attempt to meet Gentil. They had to fight off Rabih’s men as they passed Mara. Further south they ran into Rabih’s army retreating down the river from Kuno in canoes. After engaging Rabih’s bazingers, and capturing a prisoner from whom they learned that this was a small part of Rabih’s army, they turned north and retreated.

Another, stronger mission under Meynier was dispatched which traveled south and rendezvoused with Gentil at Sada on the Shari on January 13, 1900. Meanwhile, Joalland continued to bring the tribes in Kanem into the French sphere, with only one tribe resisting, whose chief was killed. Joalland returned to Gulfei where in February he received news that the Forreau – Lamy mission had reached the northern end of Lake Chad.

The expedition became a painful drudge across a visually spectacular, but barren and inhospitable landscape. Days turned to weeks - and then months of tedious marches, interrupted only by stops for a few rancid dates. The condition of the camels deteriorated until by January their health was critically low. Soon they began to drop from dysentery, malnutritian and infections from sores caused by poorly managed loads. Soon their route was marked by a trail of dead camels numbering into the hundreds.

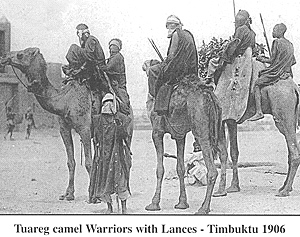

Finally, with great relief for the expedition, in February 1899 they arrived onto the comparatively lush plains of the Air - north of Agades - Tuareg country - with barely half of their camels. Here the mission set up camp and settled down as the local Tuareg chief promised the mission 500 camels. They waited some weeks and no camels arrived and the rumors that they were to be attacked grew. On March 8, one of the Chaamba and a tirailleur was murdered while out grazing the camels. Lamy prepared his troops for what was rumored to be an impending attack.

The mission was awoken on the morning of March 12 with a cacophony of sound. Here were the camels - not for sale - but supporting Tuareg warriors, each also pulling a black auxiliary - rumbling towards them, a human wave of desert warriors. Lamy quickly formed his men into a square behind the simple breastworks he had prepared, anchoring one of the corners with his 42-mm rapid-fire canon. The wall of warriors pressed closer - “You see them, the brutes!” shouted Lamy, “Well, just like at target practice”, and the French square fired volley after volley into the advancing horde. The front ranks fell, repeatedly, and those in them who tried to break off were simply trampled by the succeeding ranks that pressed on. Under heavy fire, it took the horde almost 15 minutes to advance from 500 yards to 50, the murderous volleys from the square kept them beyond their lance range. Having no firearms, the Tuareg eventually broke, without ever reaching the square and fled, leaving the scene littered with bodies.

The mission settled in to more months of monotony, unable to continue its trek due to insufficient camels. Lamy attempted negotiations with the locals and the Sultan of Agadez 200 miles to the south, but no camels were to be had. Lamy resorted to sending out raiding parties to bring back camels. Some raids were successful, others not, some bringing back human captives which were later traded back to the Tuareg for camels. When news reached them that the West African mission had crossed the Niger bend, Lamy was determined to move on and on June 8, he had ammunition and medicines loaded up on what camels were available and pressed on.

After only a few days, Lamy led a 150 man raiding party to capture more camels in the rocky hills. Returning with their loot of 3 camels and 4 horses, they were ambushed by more Tuareg causing a few casualties. They continued the southerly advance - marching in square - 100 meters on a side, the pack animals inside. On July 25, they arrived at Agadez where they set up their camp within cannon range of the walls. Weeks of interminable negotiations ensued, but the Sultan would not provide any camels, essential if the mission was to continue. At one stage, Lamy sent an armed column on into the city the to demand compliance. Finally, under threat from Lamy that they would sack the city they were supplied several hundred donkeys. After attempting to leave Agadez in August 1899, the were blasted by a desert sirocco and forced to return. A further interminable 2 months of negotiations with the Sultan of Agadez ensued, but no more camels were produced and the ability of the region to support the extra mouths dwindled. Finally, Lamy surrounded the wells with his men and stated that no one would drink until he had his camels. This did the trick and more pack animals were produced. In November 1899, Lamy finally arrived in Zinder and met up with a contingent of the West African mission’s Senegalese tirailleurs. This brought about the realization that the rendezvous of the three missions was a distinct possibility.

While the Forreau-Lamy and the reformed Voulet-Chanoin Mission under Joalland were rendezvousing at Lake Chad, Rabih was reorganizing and reforming his banners at his capital Dikwa. He recruited 3,000 new troops equipping many of them with arms and ammunition captured from weapons seized at Nyellim Hills and Kuno. Fadl Allah with 400 bazingers was sent to Gulfei, a small walled town near the mouth of the Shari at Lake Chad. Fadl Allah strengthened Gulfei and the nearby towns of Logone and Kusseri.

The Forreau-Lamy-Joalland mission reached Gulfei on January 25, 1900 and camped across the river, some 800 meters from the walls. After receiving some sporadic but hopelessly out-ranged musket fire from the walls, Joalland opened up with his 80mm mountain gun. Firing went on sporadically for some days and missions were sent out from the main French force (now under the command of Commandant Lamy) to capture or drive off small contingents of Fadl Allah’s force from the surrounding villages and towns. In one town, tirailleurs found some red British jackets bearing epaulettes embroidered with W. Riding supposedly captured from skirmishes with the Royal Niger Company.

Fadl Allah pulled back to Kusseri. On March 3, 1900 Lamy attacked Kusseri with three companies with a total number of 365 rifles - supported by two 80mm guns and one 42mm rapid fire cannon. The companies advanced in three columns. Lamy was in the center with a company of Algerian Tirailleurs, Lieutenant Rondenay on the left with another company and Meynier on the right with a company of Sudanese Tirailleurs, one platoon of which was mounted. Advancing from the Northwest, at 300 yards and now under constant musket and rifle fire, the artillery deployed. An opening was soon rendered in the wall and the Tirailleurs stormed the breach. Faced with violent bayonet charges from the Tirailleurs, many of the bazingers fell back to the eastern gate on the banks of the river. Taking to canoes, many hundreds were in the river, attempting their escape when they were spotted by the tirailleurs, who slaughtered them from the banks with accurate rifle fire. The carnage of Rabih’s forces was great, but only one tirailleur was wounded in the battle and one Mahdist style banner was captured by the mounted platoon that offered no quarter to its bearers.

After this success, the populace of the entire lower Shari region flocked to the French banner and placed them selves under Lamy’s command, eager to rid their region of the ravages of Rabih. Some 15,000 irregulars were added to Lamy’s command which now centered at Kusseri.

Forreau left the mission at this point and continued up the river system towards the Congo in continuance of his scientific mission. Meeting Gentile on his move south, Forreau brought the southern mission up to date with events at Lake Chad and Gentil began his march northwards with his own mission and 1,500 of Gaorang’s troops for the final rendezvous.

Rabih moved northwards slowly, not anxious to engage the French, but no doubt realizing the inevitability of the coming clash. Rabih was not going to assault the French, but resort to his tried and tested method of digging in and going on the defensive. This he did on April 11 at the stockaded village of Lakhta, just 5 kilometers from Kusseri just beyond the area protected by Lamy’s pickets. Deploying his cavalry in a screen around his force, he staked out a large area of high ground east of the village. Here he constructed a square earthen bank crowned with a stockade 300 meters across. The ground to the east was thick brush and the Shari lay to the northwest. The ground for 200 meters to the front of the fort was cleared of all brush and obstacles to provide a clear field. Since the brush had not been completely cleared on the left flank, nor to the rear of the position, fields of fire in these locations were occluded

Rabih’s defense consisted of 13 of his best banners including the 3rd, 6th, 27th, 28th and 29th (see issue 88) and the usual horde of auxiliaries Rabih also had the three mountain guns captured at Nyellim Hills (see issue 87).

Gentil arrived at Kusseri on April 21, 1900 and placed his force under the military command of Lamy. Gentil, the eternal diplomat, was concerned that they were in the German sphere as defined by the Berlin Conference. To avoid any future political repercussions, he enacted a legally binding treaty with the local Shehu, Sanda Kura, the rightful ruler of Borno by having him sigh a treaty with Gaorang and his allies (the French) to rid Borno of Rabih. He then appointed himself as senior political representative of France, and then authorized Lamy to attack Rabih wherever he might be found.

Rabih had prevailed at Nyellim hills through sheer weight of numbers and had used his tried and tested defensive tactics at Kuno (see issue 87) where he had fought off many bayonet charges. But he realized that the French had withdrawn due to ammunition limitations. Here at Lakhta he knew that the French were also short of ammunition and that they were running low on other supplies. The French must attack soon or withdraw, and Rabih realizing this, secured his defenses and waited. He would draw them into an attack, allow them to expend as much ammunition as they could, and when they withdrew, he would mercilessly counter-attack.

On April 22, in the morning, Lamy assembled his troops outside of the walls of Kusseri. He left a garrison of about 100 men at Kusseri under the command of Lt. Thézillat who was recovering from a bullet wound.

Soudanese Spahis

Chari Mission: Captain Reibelle

Central African Mission: Captain Joalland

Saharan Mission: Captain Robillot

The artillery was brigaded into a single battery under the command of Captain Brounoust, Lieutenant Martin and the Quartermaster Sergeant Papin

Due to ammunition shortages, especially in the Central African mission, ammunition and supplies were re-distributed. The artillery was brought up on pack camels.

Lamy’s plan was simple - to pin Rabih in place with the Central African company and the Saharan Company while the Chari companies engaged in a left flanking maneuver to the rear of the palisades, then attack simultaneously.

As the columns approached in single file, some of Rabih’s horsemen were caught off guard collecting fodder for their mounts apparently were unaware that the attack was imminent.

A kilometer from the palisades, Reibelle began his flanking maneuver moving off to the left. Joalland’s force began it’s advance on the right and Robillot was held back in reserve ready to support Joalland as needed.

Brounoust began an intense artillery barrage on Rabih’s fort while the tirailleurs crawled forward under the heavy return fire of the bazingers. For two hours, the tirailleurs lay in the hot sun trading fire with bazingers - ammunition re-supply and water being brought up from the camel train to the rear.

At the point that he felt the bazingers had been softened - in fact many had fled their position at the palisades under the fierce fire - Lamy ordered the charge. As the bugles blared - the tirailleurs rose from the dusty stubble and charged the palisade. The tirailleurs charged for the small gates, barely a meter wide as lacking any sort of siege ladders, the log wall was a formidable obstacle. Despite many bazingers having deserted the wall, the bodyguard banners put up a tremendous defense but tirailleurs, bayonets fixed, were equally furious and a terrible carnage ensued.

Rabih’s bazingers fell back from the fort and retreated south. Rabih managed to rally his bodyguard banners and counter attacked the fort. Lamy and his staff had entered the fort, his troops, and particularly the Bagirmians were looting and pillaging the dead and dying. Rabih’s counter attack poured fire onto Lamy’s group killing several officers and mortally wounding Lamy.

Lamy is Wounded Illustration (slow: 109K)

It was another year of continuous skirmishing before the remnants of Rabih’s army under Fadl Allah were rounded up and defeated and almost a decade before As Sanusi (see issue 88) was assassinated by the French. Rabih’s rule had been brought to an end. His tactics and well-trained army far outmatched any indigenous opposition that could be brought to bear on him, but against the French - he was equally outmatched. Even in the carnage of the final battle, which saw the death of over 1000 of Rabih’s bazingers, only 28 tirailleurs had been killed and 75 wounded. The French had expended 32,000 rifle rounds and 94 artillery shells.

Correction to Part II

My automatic spell-check replaced the name of Rabih’s Lieutenant, al Sanusi, with the name al Sansui ( a Japanese Hi Fi manufacturer). Al Sanusi reigned in the Dar El Kuti region as Rabih’s lieutenant, was responsible for the attack on Crampel’s mission and was assassinated by the French in 1911 at Ndele. - Ian Croxall

Already corrected in MagWeb.com archive.

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 3

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 2

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 1

That night, Bastille Day, July 14, 1899, Voulet told his officers what he had done. He renounced his citizenship and declared that he was going to establish an empire for him self in the Western Soudan. He addressed his black sergeants in the same manner and invited them to become his chiefs and support him as Warlord of the region. The officers declined to participate realizing that he had gone too far. They and 30 tirailleurs returned to Sey and united with Meynier’s group.

That night, Bastille Day, July 14, 1899, Voulet told his officers what he had done. He renounced his citizenship and declared that he was going to establish an empire for him self in the Western Soudan. He addressed his black sergeants in the same manner and invited them to become his chiefs and support him as Warlord of the region. The officers declined to participate realizing that he had gone too far. They and 30 tirailleurs returned to Sey and united with Meynier’s group.

When Meynier had recovered from his wounds, the column was marched to Zinder with the hopes of meeting the Forreau – Lamy expedition. Zinder was attacked and easily taken. However, by this time, discipline had been so eroded that a second mutiny broke out which was put down, but not before another 45 tirailleurs had been killed. This took Pallier to the end of his tether. He relinquished command to Lieutenant Joalland and returned to Senegal with 300 men, Dr. Henric and two sous-officers – he died on his way to France.

When Meynier had recovered from his wounds, the column was marched to Zinder with the hopes of meeting the Forreau – Lamy expedition. Zinder was attacked and easily taken. However, by this time, discipline had been so eroded that a second mutiny broke out which was put down, but not before another 45 tirailleurs had been killed. This took Pallier to the end of his tether. He relinquished command to Lieutenant Joalland and returned to Senegal with 300 men, Dr. Henric and two sous-officers – he died on his way to France.

The Forreau-Lamy Mission

The Forreau Lamy Mission set out from Ouargla in October 1899 to cross 2000 miles of the Sahara, its destination, Lake Chad. The mission was put together on the fly with 380 inexperienced Tirailleurs and 1004 poorly managed camels. Food and water soon became short in supply and the camels succumbed to festering sores. The mission had brought insufficient flour for bread and the Chaamba Arabs hired to hunt gazelles and antelope hardly provided enough game to support themselves.

The Forreau Lamy Mission set out from Ouargla in October 1899 to cross 2000 miles of the Sahara, its destination, Lake Chad. The mission was put together on the fly with 380 inexperienced Tirailleurs and 1004 poorly managed camels. Food and water soon became short in supply and the camels succumbed to festering sores. The mission had brought insufficient flour for bread and the Chaamba Arabs hired to hunt gazelles and antelope hardly provided enough game to support themselves.

The Showdown

Lamy’s Order of Battle

Lamy’s Order of Battle

Three companies (Galland, Cointet and Lamothe) - total 340 men each with 500 rounds, two 80mm mountain guns with 250 rounds each.

One company - 174 men (of whom 20 were mounted) with almost 300 rounds per man and a single 80mm piece with 30 rounds.

Totaling 274 rifles with 180 rounds per man and a 42mm rapid fire cannon. These numbers include a troop of 10 mounted Algerian Spahis.

Baguirmi contingent.

400 bazingers and 200 mounted warriors - all armed with firearms.

The tirailleurs launched a savage counter attack against Rabih’s group, which was driven away in rout. Rabih was wounded and left by a bush where a tirailleur spotted some movement and fired into the bush -- hitting Rabih in the head. When informed that there was a bounty on Rabih’s head, the tirailleur returned and retrieved the head. Bringing it back to the fort, the dying Lamy asked if it was true that Rabih was dead. Lamy died later in the knowledge that he had defeated his enemy - and was buried at Kusseri and the fort that followed was to bear his name.

The tirailleurs launched a savage counter attack against Rabih’s group, which was driven away in rout. Rabih was wounded and left by a bush where a tirailleur spotted some movement and fired into the bush -- hitting Rabih in the head. When informed that there was a bounty on Rabih’s head, the tirailleur returned and retrieved the head. Bringing it back to the fort, the dying Lamy asked if it was true that Rabih was dead. Lamy died later in the knowledge that he had defeated his enemy - and was buried at Kusseri and the fort that followed was to bear his name.

Part Three: The Fall of Empire

Part Three: The Many People of Rabih's World

Part Three: Wargaming the Period

Part Two: Rise to Dominance

Part Two: Rabih's Army

Part Two: Organization of the Banners (very slow: 212K)

Part Two: Gentil's Missions 1897-1899

Part Two: Jumbo Color Illustration: Rabih's Warriors (slow: 319K)

Part One: Battle of Nyellim Hills

Part One: A Leader Emerges

Part One: The Years Under Sulaiman

Part One: Azande Warfare

Part One: Jumbo Map of Central Sudan (slow: 116K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 89

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com