When Rabih fled Sulaiman’s camp at Giga in 1879, he had less than a thousand men with him. There are conflicting reports on exactly how many men, but however many there were initially, they were quickly reduced by desertion and by his leaders being captured and executed by the pursuing authorities. His numbers may have been reduced to as few as 125.

After fleeing into Dar Fur, Rabih raided and traded his way south and east through the Central Sudan. For several years in the early 1880’s Rabih raided along the borders of Dar Kresh and the northern Mbomu river valley in Azande Land (see map in last article). This raiding took him westward as far as the Ubangi Valley and by 1884 Rabih’s Army strength was at 15,000 men. Rabih then turned north into Dar Rung and Dar al Kuti on the borders of the Wadai Sultanate to the north.

Sultan Yusuf of Wadai was becoming very concerned with this large military empire building on his borders. Rabih attempted a peaceful approach with Yusuf and requested that Yusuf leave open the trade routes so that armament shipments would continue to reach him from the north. Yusuf’s reaction was to shut down the flow of commerce all together resulting in a major attack from Rabih into the Wadaian vassal governorship of Dar Runga.

The first attack was a victory for Rabih, but some other attacks were indecisive. The Wadaian Sultan re-opened the trade links but still prevented armament shipments from reaching Rabih.

To the south was the Sultanate of Bagirmi ruled by Gaorang II whose capital was at Massenya. The 1850’s German explorer Heinrich Barth as a run down dilapidated town described this. In 1889 Rabih attacked some of the northern tribes of Bagirmi, vassals of Sultan Gaorang, and was operating in the Shari River valley south of Lake Chad. In 1890, Rabih left Bagirmi and returned to Dar al Kuti to re-establish his eastern trading routes and to re-build his army.

Rabih was now only receiving limited supplies from Bornu around Lake Chad to the northwest. In December 1890, Rabih moved his camp and set up his army base at Kusseri near Lake Chad in the lower Shari River valley. Before he left he installed al-Sansui, one of his lieutenants, as Sultan of Dar al-Kuti.

Although al-Sansui was a benefactor and dependent of the Rabih, al-Sansui did himself benefit from his trading locations near to the secondary empires of Wadai and the Mahdi, just as Rabih had done before him.

Once Rabih had moved out of Dar al Kuti, Sultan Yusuf reopened the trading routes to all commerce except arms and ammunition.

Crampel Mission 1891

In 1891, within a month of Rabih’s departure, a French expedition led by Paul Crampel entered Dar al-Kuti and presented the new sultan, al-Sansui with an opportunity to begin his ascendancy to independence from Rabih. Crampel’s mission arrived carrying 50 modern rifles (Kropatchek, Gras and Remingtons) and 175 flintlocks, 30,000 rounds, 60,000 percussion caps (very difficult to obtain and beyond the manufacturing capabilities of most African nations – hence their continued dependence on flintlocks) and about ½ ton of Black Powder.

When Crampel told al-Sansui that he was heading north, to either Rabih’s camp or the Wadaian Sultanate, al–Sansui was concerned. Sansui speculated that if Crampel arrived with this amount of weaponry, Rabih would attack Crampel and add the prize to his arsenal – even further subordinating al-Sansui to Rabih. Al-Sansui was also concerned about Wadai as he had accepted power in Dar al-Kuti (a land formally a vassal of Wadai) from Rabih without Wadaian approval and the Sultan considered Sansui a rebel. Here was Sansui’s opportunity to provide himself the means to redress the armament imbalance.

So, as Crampel set off, despite al-Sansui’s requests the he not to go north. Al-Sansui sent several detachments ahead to ambush the expedition. Crampel, along with most of the Tirailleur Senegalese were killed in the attack. At least one tirailleur survived and became a military instructor for al-Sansui’s army. A second contingent of the Crampel mission commanded by Gabriel Biscarrat was attacked a few days later it’s weapons assimilated into al-Sansui’s army.

Rabih was angry at the killing of Crampel and ordered al-Sansui to send him the captured armaments and the 12 captured Senegalese tirailleurs. From these and other contacts, Rabih was becoming aware of the huge power behind these exploratory expeditions, the vanguard of the “Great Scramble”. In 1899 Rabih also made contact by letter with his friend Zubair, whom the British was release and had employed under General Wingate, providing further insight as to what may lay ahead.

Rabih invaded Bagirmi in 1892. He moved south by boat while his army advanced along the shore. Sultan Gaorang’s army, unlike Rabih’s, was dominated by cavalry and was used in a preemptive attack against Rabih’s banners as they approached Banglama. As Rabih had little reliance on cavalry, they had to defend on foot. Alerted to the advancing Cavalry army, they prepared a defensive perimeter of thorn barriers behind which the riflemen could fire on the horses. This they did effectively and broke the attack, which fell back on Banglama. Rabih’s army advanced on Banglama killing many Bagirmians. Gaorang survived and fell back on Manjaffa.

The Siege of Manjaffa 1892

Rabih followed up relentlessly and placed Manjaffa under siege. He built siege redoubts around the town that would have been the envy of any 18th century European army commander. From here he poured rifle fire onto the defenders and attacked repeatedly for 2 days, in one assault loosing 400 of his banner troops. Manjaffa was a fortified town with walls 6 meters high and 2 meters thick. Following the initial attacks, the siege entered a stage medieval in scope. The defenders resorting to boiling water and incendiary bombs against their attackers. For four months, they held put. Food ran out and the defenders resorted to eating dogs. Messengers were sent to appeal for help from Wadai. Units for Sara came to Manjaffa’s aid but were driven off by Rabih’s banners, which had been called up as reserves from the Shari. A relief column from Wadai did attack from the north with over 2,000 rifle-armed cavalry. Rabih’s excellent communication system also alerted him to their arrival and he placed his 23rd banner leader Tokoloma in charge of their interception. Tokoloma was trained as an engineer in the Khedival army and had ridden as a leader with Zubair. He quickly drew up entrenchments to intercept the advancing Wadaian force in which he placed his rifle-armed bazingers.

Gaorang sent a sortie from Manjaffa to rendezvous and assist the arriving Wadaian relief column but all they found on their arrival was 1,000 dead Wadaian troops - the beaten survivors having withdrawn.

One of Rabih’s soldiers, Faki Na’im from Uthman Sheku’s 10th banner had previously suggested a plan to Rabih which had been rejected. Rabih now consented to the ploy. Faki, with three handpicked bazingers killed one of the guards and stole into Manjaffa at the point where the river entered, under cover of darkness. They set fire to several buildings and began shouting and firing their rifles. The Bagirmian defenders thought a much larger force had gained entry to the town and they fled and broke out of the perimeter, Gaorang escaping to the North.

Rabih was impressed with the brave defense put up by the defenders and in a rare act of mercy prevented his army from completely sacking the town.

The Invasion of Bornu 1893

After Manjaffa Rabih came to the decision that Bornu must also be invaded to solidify his power base on the lower Shari south of Lake Chad. He established a series of garrisons along the Shari River.

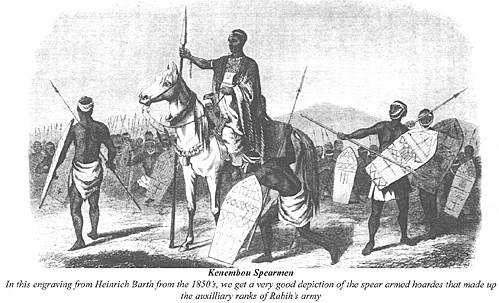

From here, Rabih could launch his invasion of Bornu. Forty years earlier, the German explorer Heinrich Barth provided a descriptive account of a Bornu Army on the march.

The Battle of Amja River 1893

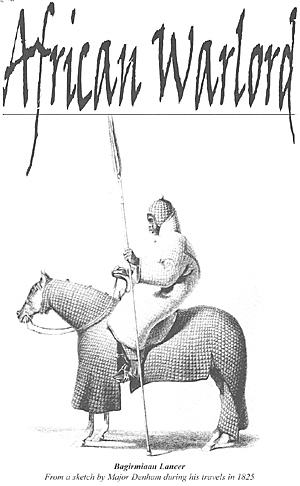

An army of 10,000 such Bornu troops was sent to oppose Rabih. Again, Rabih was greatly outnumbered in cavalry. About half of these were regular troops arranged into 12 banners, 6 of infantry and 6 cavalry. These comprised a mixed bag of troops types, from mail clad lance armed cavalry to musket and bow armed infantry. Under command of Mohamed Tahar, the Bornu army arrived at Dikwa on the Shari River looking for Rabih. He had moved to a large clay plain on the Amja River.

Although it was the dry season, a freak storm had left a boggy marsh spot in the plain on which Rabih anchored his flank. The next day, Tahar’s army found Rabih and attack with a headlong cavalry charge. As was becoming the standard response, Rabih’s’ Remington armed rifle troops broke the charge. The Bornu cavalry broke off and launched a second attack against the flank, becoming quickly mired in the swamp. Forced to dismount, the attackers were shot down in the swamp unable to maneuver.

Hearing of the attack at Amah, Gaorang attempted to reinforce Bornu from the south but was too late and broke off the attack on hearing of Tahar’s defeat.

The Battle of Lagara 1893

On hearing of Tahar’s defeat, the Bornu Shehu (sheik) Hashim mustered an army of 6,000 horsemen and a large slave levy of infantry and 12 cannon and marched south to intercept Rabih. This was assembled on a large plain in Bornu at Lagara, but Rabih had been alerted to this by his excellent reconnaissance. Now having a full appreciation of Central Sudanese cavalry tactics, Rabih expected a full frontal cavalry charge form his opponent and was not to be disappointed. He placed his rifle-armed bazingers in the center on the river, using its bank as cover with 2 cannons in the center. He anchored his flank with his two small cavalry troops.

Shehu Hashim began the attack with the predictable large-scale headlong cavalry charge and used his slave levy to attack Rabih’s left flank. The Remingtons and cannons devastated the cavalry charge that was forced to withdraw. Rabih’s left flank was on the point of collapsing under the slave assault when due to the collapse of the enemy center, he was able to wheel on the left flank and save it from collapse. Shehu Hashim was unable to employ his cannon and they were captured when Rabih pursued the defeated enemy.

Rabih pursued Hashim who refused to defend Kanem, the capital and it was completely sacked and ravaged by Rabih’s army. Rabih retired to his capital, Dikwa on the Shari River having defeated the two largest powers in the Central Sudan.

The Battle of Gashegar 1894

After the destabilizing effect of Rabih’s invasion, an internal power struggle led to Abba Kyari, a nephew of Shehu Hashim, assassinating him and declaring himself Shehu. He immediately challenged Rabih who responded by leading a force of 700 bazingers to challenge Shehu Kyari near Gashegar.

Arriving ahead of Kyari, Rabih prepared earthworks on the banks of a small stream, Yobe, by the town of Dumurwa. He detached a rear guard of 50 men perhaps expecting that he might be forced to fall back with his small army and that they might serve as a rallying point. Shehu Kyari divided his force into two wings and attacked each flank simultaneously. The 5th and 11th banners gave way and as night fell, Rabih’s forces fell back in disarray. Kyari failed to exploit his victory and his men fell on Dumurwa to loot it - intending to follow up on Rabih in the morning.

Rabih had his detachment, a mile to the rear, blow its horns and bang the war drums to serve as a rallying point for the men pulling back from the battle line. He reorganized his banners and counter attacked Dumurwa in the dark. Dumurwa was now blazing and some of Rabih’s previously hidden gunpowder ignited causing confusion. In the light of the burning huts, the Bornu soldiers were shot down by the attacking bazingers and in panic many of them broke out and fled. Shehu was trapped down by the river and caught with a small retinue of bodyguards and personal slaves. He put up a valiant defense and was attacked several times before succumbing. He was captured, but was defiant still to Rabih who then had one of his slaves slit Shehu Kyari’s throat.

Rabih spent the rest of 1894 sending out columns from his base in Dikwa and by early 1896 had subdued much of Bornu, whose princes’ resistance dwindled with each skirmish. Rabih’s hold on Bornu was consolidated, and due to Gaorang’s continued activity to the south, Rabih penetrated no further to the west and north.

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 2

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 1

The Battle of Banglama 1892

The Battle of Banglama 1892

“Heavy cavalry, clad in thick wadded clothing, others in their coats of mail, with their tin helmets glittering in the sun, and mounted on large heavy chargers, which appeared almost oppressed by the weight of their riders and their own warlike accoutrements; the light Shuwa horsemen, clad only in a loose shirt; and mounted upon their weak unseemly nags; the self conceited slaves, decked out gaudily in red burnoose or silken dresses of various colors; the Kanembu spearmen, almost naked, and their large wooden shields, their half-torn aprons round their loins, their barbarous head-dresses and their bundles of spears; then in the distance behind, the continuous train of camels and pack oxen.”

Part Two: Rise to Dominance

Part Two: Rabih's Army

Part Two: Organization of the Banners (very slow: 212K)

Part Two: Gentil's Missions 1897-1899

Part Two: Jumbo Color Illustration: Rabih's Warriors (slow: 319K)

Part One: Battle of Nyellim Hills

Part One: A Leader Emerges

Part One: The Years Under Sulaiman

Part One: Azande Warfare

Part One: Jumbo Map of Central Sudan (slow: 116K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 88

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com