This action in the sub Saharan scrubland known as the Sahel was a costly victory for Rabih Fadl Allah. It was to be his last great victory and found him at the pinnacle of his empire. Three great columns, instruments of French Imperialism were closing in on their objective – the Inland Sea of Lake Chad.

This action in the sub Saharan scrubland known as the Sahel was a costly victory for Rabih Fadl Allah. It was to be his last great victory and found him at the pinnacle of his empire. Three great columns, instruments of French Imperialism were closing in on their objective – the Inland Sea of Lake Chad.

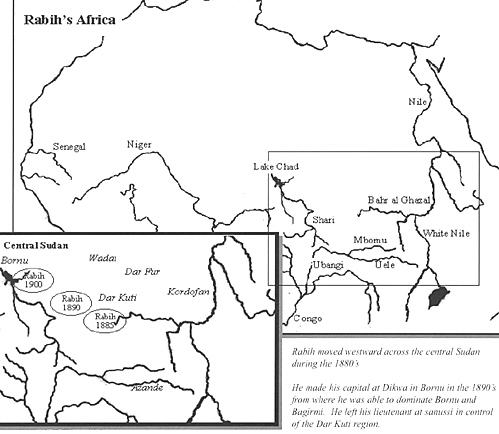

But who was Rabih Fadl Allah and why is so little known about him outside of Central Africa? The French missions fought their way across the harshest of the world’s environments, fighting skirmishes and pitched battles along the way. The climax of their forays into the heart of Africa was to be a clash with one of the largest of the African Empires, that of Rabih. This was still a few weeks and a few battles away but the die was now cast.

In this article we will introduce the history of the region, the peoples and describe the battles, uniforms, weapons and tactics. We will try to inspire with photographs and period illustrations. We will discuss appropriate figures and organizations necessary to game this period. Scenarios are presented with a mind to Colonial Rules such as The Sword and the Flame and Soldiers Companion. These can readily be adapted to other colonial rule sets of ones choice.

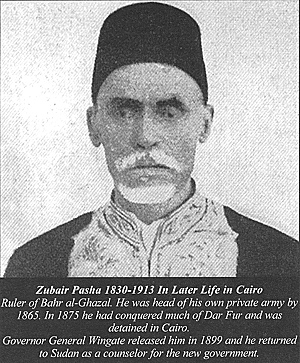

Zubair Pasha and Rabih’s Early Years

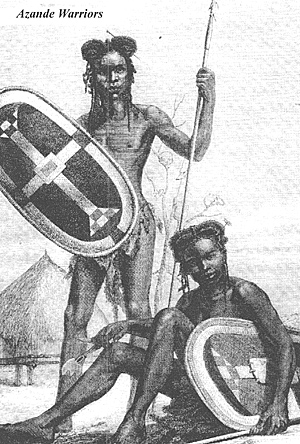

Gordon of Khartoum described Zubair Pasha as the greatest slaver who has ever lived. Along with his son Sulaiman, Zubair established a vast slave trading empire in southern Kordofan. The trading was centered at the markets of Khartoum and began to flourish in the 1860’s. Zubair, who had come from humble beginnings, financed his first independent slaving mission in 1858. He recruited a company of 25 men and departed up the Nile on a boat he had purchased in Khartoum. This expedition took him into Azande territory of the upper Sudan and the realm of Chief Tikima north of the Mbomu river. Zubair established friendly relations with Tikima by supporting him militarily against his regional enemies. Tikima rewarded Zubair with one of his daughters after Zubair was wounded in a skirmish.

Returning to Khartoum in 1860, Zubair had achieved enough profit to form a larger army of 200 guards with which to launch a second mission into the upper Sudan. One of these guards was Rabih Fadl Allah whom Rabih had met during a chess game in Khartoum. Rabih was about 20 years of age, had received a koranic education, and possibly had served the Khedival army in a Sudanese battalion. It is also quite likely that he was a horseman as he had a permanently injured third finger of his right hand reportedly caused by a fall from a horse during military maneuvers.

Although Rabih had quite possibly been a slave at one time, he was probably not a slave of Zubair. However, the distinction between slave and free-born was little more than titular in the totalitarian military regimes of Zubair and later Rabih.

Although Rabih had quite possibly been a slave at one time, he was probably not a slave of Zubair. However, the distinction between slave and free-born was little more than titular in the totalitarian military regimes of Zubair and later Rabih.

Initially Zubair created a working relationship with the Azande chiefs, this eventually turned to conflict as more and more Azande were carried off to the Khartoum slave markets. Eventually forced away after a series of skirmishes, Zubair established his own zeriba (fortified village whose name is usually preceded by “Dem”) from which to defend his position. Over the next several years Zubair fought off the Azande tribes, created a string of zeribas in the Kresh Ndogo region, and dominated the trading routes through Kordofan to Dar Fur and Khartoum. This power base also led to the control of the valuable regional copper mines. During this period, the strength of Subaru’s army rose to some 12,000 bazingers that were needed to dominate the caravan routes and garrison the zeribas.

Zubair’s expansion necessitated establishing trading relations with the Rizaiqat Arabs of Dar Fur. The raiding into the Azande areas subsided to some extent as the Azande emulated the Khartoum’s’ tactics. In 1870, chief Ndoruma of the Azande defeated a Khartoumer expedition of 2,000. In the same year, Zubair again turned his attention south towards the Azande.

In 1869, the Khedival government attempted to bring the Khartoumers (as the slave raiders and traders became known) under their authority. Most submitted, but Zubair maintained his independence and was eventually considered a rebel. In 1872 Jafar Pasha, the Governor General, sent reinforcements to his local commander and Zubair was attacked. Zubair immediately rose to the challenge. It is during this battle that Rabih emerges as a reliable and ruthless commander at the head of his own banner. The years of campaigning, skirmishing and jungle warfare had hardened this force to the extent that the Khedival troops were no match for Zubair’s army.

Zubair made political moves in Khartoum to the effect that he had reacted to rogue elements of the Khedival forces whose local commanders he alleged were acting in their own self interests and an Inquiry was begun in Cairo. Zubair was at the pinnacle of his career. His slave exports were in excess of 50,000 souls per year and supported by massive amounts of ivory, copper and other valuable trading commodities. His army of 12,000 was officered mostly by Jalayin Arabs, often relatives of Zubair. Some commanders were trusted friends, such as Rabih, or occasionally slaves risen through the ranks. Most of the army were recruited or pressed into service from the surrounding tribes. Many of his troops were cannibals whose excesses were encouraged to inflict psychological terror on the enemy. However, the cannibalistic acts were not tolerated outside of battle and were forbidden during the short periods of peace that punctuated Zubair’s military career.

Battles

It is important to detail some of Zubair’s major battles, as his tactics are an obvious influence in Rabih’s latter tactical considerations. Sultan Hussein of Dar Fur, with whom Zubair had established trading treaties, died in 1872. His son Ibrahan Hussein succeeded him. Zubair immediately complained that the wild Rizaiqat tribes of Dar Fur, who still attacked his caravans, were Hussein’s subjects and held him responsible. Without waiting for a response, Zubair invaded Dar Rizaiqat with a foot army of 4,500 bazingers in February 1873.

Over 600 of Zubair’s army died from sickness on the march, plagued by terrible weather. A journey of 12 days took “forty” days and the troops were driven on remorselessly by Rabih and other ruthless banner commanders. Arriving in Shake, Zubair’s tired and bedraggled troops were immediately attacked by 15,000 mounted Rizaiqat Arabs. All evening, Zubair’s army was attacked, but it formed and maintained disciplined firing lines and was able to break charge after charged with accurate rifle and musket fire that broke the ranks of the cavalry. Despite surrounding Zubair during the night, the Rizaiqat army was defeated the next morning and was forced to withdraw. Zubair had captured more than 600 horses that began a cavalry arm for his army.

This was Rabih’s first experience of the large cavalry armies with which he was destined to become so familiar in the years to come in the Central Sudan but also that the tactic to defeat them was a controlled and disciplined infantry rifle firing line.

Zubair was joined by two Rizaiqat Arab chiefs and over the next seven months was able to bring Dar Rizaiqat under effective occupation. There was some speculation at this time that Zubair was the coming Mahdi, the expected one and even Abd Allah at Ta’aishi (who was later to become chief kahlifa to the Mahdi) whose life Zubair had earlier spared, had written to Zubair asking if he was indeed the “expected one”.

At the end of 1873, Zubair declared war on Dar Fur. At the same time, the Cairo inquiry ruled favorably for Zubair. He was promoted to Bey and granted Governor Generalship of Bahr al Ghazal, an awkward position for the Khedival government who recognized that he was the only person who could keep order, but at the same time the Khedival government had officially abolished slavery. He was rewarded by reinforcements of regular soldiers and cannon.

In January 1874 Sultan Ibrahim sent a force of 31,000 foot, 9,000 cavalry and 23 cannons to challenge Zubair’s position. Zubair’s Rizaiqat allies informed him they would only support him in the event he was victorious in the ensuing battle. Including his recently provided reinforcement of regular troops, Zubair had 5,000 men and artillery at his disposal.

Losing 400 men to a preliminary skirmish, Zubair retreated to prepared positions at Abu Sigan. Disciplined protected firing lines again showed that they could break the ranks of mass cavalry charges. As the Dar Fur cavalry attacks were disordered and began to break, Zubair’s Rizaiqat allies descended on the flanks of the attackers and took them to rout. The defenders followed up in an orgy of cannibalism. The number of Dar Fur dead is not recorded. Zubair captured all 23 cannons, 27 camel loads of ammunition and over 2000 armored breastplates. Some of the cannon were hundreds of years old and of pure copper. A second and third army sent by Sultan Ibrahim met similar fates over the next month.

Losing 400 men to a preliminary skirmish, Zubair retreated to prepared positions at Abu Sigan. Disciplined protected firing lines again showed that they could break the ranks of mass cavalry charges. As the Dar Fur cavalry attacks were disordered and began to break, Zubair’s Rizaiqat allies descended on the flanks of the attackers and took them to rout. The defenders followed up in an orgy of cannibalism. The number of Dar Fur dead is not recorded. Zubair captured all 23 cannons, 27 camel loads of ammunition and over 2000 armored breastplates. Some of the cannon were hundreds of years old and of pure copper. A second and third army sent by Sultan Ibrahim met similar fates over the next month.

This was Zubair’s greatest military achievement and he was promoted to the rank of Pasha. But the Khedival government sought to restrain him and ordered him to take the defensive, they then ordered Ismail Pasha Ayyub, Governor General of Sudan, to take over the offensive. Ayyub was ordered to subjugate Dar Fur despite protestations from Sultan Ibrahim that it was Zubair that was the aggressor, not he. Zubair, understanding that the government was trying to restrain him ignored the order and advanced on Dar Fur. He now had a large enough army to completely subdue Dar Fur, and arriving at Dara in June 1874, he occupied the town. He built fortifications and surrounded the town with a ditch 12 feet wide and 12 feet deep.

On the way to Dara, Zubair had been slowed by a series of skirmishes. Sultan Ibrahim was unable to build his new army prior to Dara’s occupation but was subsequently able to besiege it. Zubair held off the siege for 4 1/2 months fighting off attack after attack with disciplined rifle fire from prepared positions. After the new Dar Fur army had blunted itself against the prepared positions, it withdrew. It was immediately followed up and attacked repeatedly and relentlessly. Ayyub Pasha was in the meantime attempting to catch up with Zubair, whom he felt was stealing his glory.

Sultan Ibrahim fought one last engagement with Zubair and in a forlorn hope charged Zubair’s lines to engage him in personal combat, he was brought down in a hail of bullets. Respecting this bravery, Zubair buried him with full honors. Dar Fur’s capital was sacked and its great riches shared amongst leaders of Zubair.

Ayyub Pasha was furious at Zubair who remained restrained now that he had a taste for military greatness under the authority of the government. He obeyed Ayyub’s order to continue mopping up Dar Fur while he, Ayyub, took credit for the conquest.

In 1875, Zubair Pasha fell into disagreement with Ayyub over methods of taxation and they both went to Cairo to make their cases to the government. Zubair arrived in Cairo in 1876 with 1000 bodyguards, while leaving 6000 of his regular bazingers -- including Rabih -- under the command of his son Sulaiman. The Khedival government heard his case and after five months of prevarication, Zubair was informed that he would not be allowed to return to the Sudan. This was an action Zubair had not foreseen and going to Cairo turned out to be Zubair’s greatest tactical error. He was provided with a household and a pension and did not return to the Sudan for nearly 25 years.

While Zubair’s early career had given Rabih a sound foundation in raiding, hit and run and other small-scale tactics, the latter actions had provided the basis for his tactical education and Rabih became an experienced military commander. The tactics learned under Zubair were to recur over the next 25 years: Carefully selecting the ground over which the enemy must fight and reinforcing natural defensive features with fortifications. Providing a steady discipline rifle fire to break up enemy and allowing the enemy to blunt itself with repeated attacks. Then, when it was sufficiently weakened, fighting back at the enemy with repeated attack after attack, remorselessly, never letting up or allowing the enemy to regroup.

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1874 – 1911 The Rise and Fall of the Empire of Rabih Fadl Allah

-

Part One: Battle of Nyellim Hills

Part One: A Leader Emerges

Part One: The Years Under Sulaiman

Part One: Azande Warfare

Part One: Jumbo Map of Central Sudan (slow: 116K)

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 2

-

Part Two: Rise to Dominance

Part Two: Rabih's Army

Part Two: Organization of the Banners (very slow: 212K)

Part Two: Gentil's Missions 1897-1899

Part Two: Jumbo Color Illustration: Rabih's Warriors (slow: 319K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #87

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com