Organization

Organization

Rabih’s army was organized along European lines because of Egyptian influences received in his early military career. By the time Rabih had moved to Bornu his army was averaging 3000 – 4000 bazingers in his banners with 6000 auxiliaries which was increased to as many as 16,000 at its height. Six hundred of the bazingers formed the three main garrisons along the Shari River. The more than 4000 rifle or musket armed troops of the Banners formed the core of his force. The banners were the main units into which his army was divided. The most senior banners were the 28th and 29th bodyguard known as the Sultans bodyguard banners. The head of each banner was drawn, where possible, from the original followers of Rabih but some were also trusted and loyal slaves who had been assimilated during Rabih’s expansion.

By the time Rabih moved to Bornu, local leaders there also became banner leaders. One or two lieutenants supported each banner leader. These were the senior officers of each banner and had overall command of the NCOs, each of whom controlled 30 –50 bazingers. The senior banner officers were all Muslims and mostly either Jalayin or Ta-aisha Arabs. The rank and file was made up of the various pagan and nominally Muslim peoples assimilated by Rabih’s expanding empire. Where possible recruits were kept together in their own ethnic groups but commanded by the Sudanic officers. The original recruits were predominantly from the upper Sudanic groups of Kresh, Nuer, Dinka and Azande, but latter supplemented by reinforcements of Banda, Sara, more Azande and other smaller ethnic groups as Rabih moved westwards.

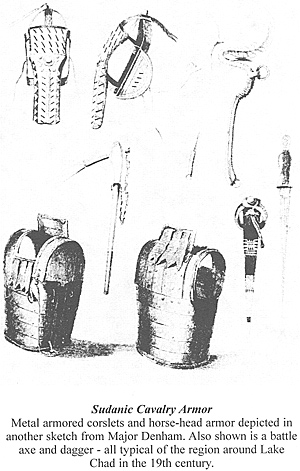

Cavalry were not heavily relied on, particularly early on, but when used were attached to banners in small sections as tactical situations warranted. As Rabih moved westwards, cavalry was added from local chiefs willing to provide mounted contingents in exchange for political consideration. As in western armies, the foot soldiers of Rabih appear to have regarded the cavalry with some degree of contempt, but unlike western armies, the cavalry did not attain a superior status to the infantry.

By the time Rabih was settled at Dikwa, more horses were obtained to provide transportation for his Banners and were used as mounts for mounted infantry.

Recruiting

Recruits were added through raiding and slaving, captives being pressed into service upon capture. Those who agreed to military service went through a 6-day period of rigorous recruit training and upon acceptance were mustered into the banner to continue honing their skills as a bazinger. Providing there were sufficient supplies, the recruit was issued a firearm and paid a small wage. Those found unsuitable were sold into slavery or executed. Those not willing to participate at the outset were immediately dispatched.

Volunteers were also added to the army and after the battle of Gashegar, some units from Bornu’s army defected to Rabih with whom they remained until his defeat. There are reports that some remnants of the Khalifa’s army went over to the Rabih in 1899 after its defeat. Some remnants of the Mahdiyan army were fighting the French for the Sultan of Wadai after Rabih’s fall on into the 20th century.

Volunteers were also added to the army and after the battle of Gashegar, some units from Bornu’s army defected to Rabih with whom they remained until his defeat. There are reports that some remnants of the Khalifa’s army went over to the Rabih in 1899 after its defeat. Some remnants of the Mahdiyan army were fighting the French for the Sultan of Wadai after Rabih’s fall on into the 20th century.

Weapons

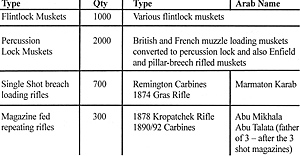

In the 1890’s, Rabih’s armaments were estimated at some 4000 firearms. The majority of the modern weapons were short breech loading Remingtons brought from the eastern Sudan with Rabih’s initial departure but continued to be supplied from there when possible. Their numbers were naturally limited and they were supplied to the 28th and 29th bodyguard Banners, which can be considered Rabih’s elite units. The remaining weapons were distributed amongst the other banners, and those left over were kept in arsenals in Dikwa for re-supply when needed.

Ammunition supply was always problematic. Empty cases were salvaged and re-loaded with locally made powder and cast bullets. Powder manufacture was supplemented by trade powder and that taken from other sources such as the large quantity captured from the Crampel mission by Sansui, much of which ended back in Rabih’s camp. Powder had been manufactured locally since at least the 1850’s when Barth described seeing its manufacture during his visit. Sulfur was the only imported ingredient, which, along with percussion caps was brought by the Trans-Saharan caravan routes. Percussion caps were also sporadically imported from the Sudan markets in the east.

Ammunition supply was always problematic. Empty cases were salvaged and re-loaded with locally made powder and cast bullets. Powder manufacture was supplemented by trade powder and that taken from other sources such as the large quantity captured from the Crampel mission by Sansui, much of which ended back in Rabih’s camp. Powder had been manufactured locally since at least the 1850’s when Barth described seeing its manufacture during his visit. Sulfur was the only imported ingredient, which, along with percussion caps was brought by the Trans-Saharan caravan routes. Percussion caps were also sporadically imported from the Sudan markets in the east.

The capture of arms and ammunition such as at Nyellim Hills was a welcome if infrequent relief to the supply problems. Despite shortages, training was never overlooked, and Rabih would personally oversee the rigorous training of his bodyguard banners, which included marching as well as tactics and weapon drill.

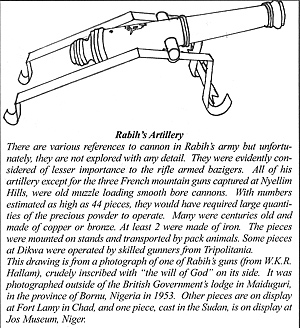

Rabih certainly had artillery, but it is rarely mentioned. Some estimates place the number of pieces as high as 44. These were large naval type muzzle-loading cannon, some made of pure copper, but at least two were iron. Rabih also captured three 8cm Krupp guns at Nyellim Hills. The French at Kusseri captured two of his muzzleloaders. These were named Tokkor and Kafar. Finding suitable gunners appears to have been problematic and at Dikwa, the gunners are noted as being Tripolitanian. The artillery was not limbered or wheeled, but mounted on stands and transported by pack animals.

The army baggage was moved by large quantities of pack animals, which were also an essential element for delivering trade goods. In 1895, Dikwa was estimated to contain 1000 horses, 500 donkeys, 500 camels and 400 mules.

Uniform

Uniform

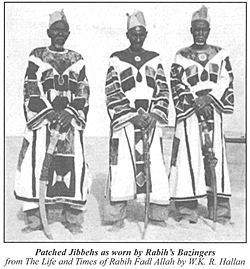

Rabih uniformed his bazingers in the traditional Sudanic Jibbeh that were greatly elaborated with patches of color. This was copied from the false patches adorning the jibbehs of the Mahdists army in whose name Rabih at one time claimed to ride. The cloth, named balta-balta was an important trading commodity in Dikwa. In this picture, taken in 1960, these bodyguard troops of a Shehu in Bornu (now in Nigeria) can be seen wearing the patched Jibbeh, changed little the 60 years since the days of Rabih.

Standards

Standards

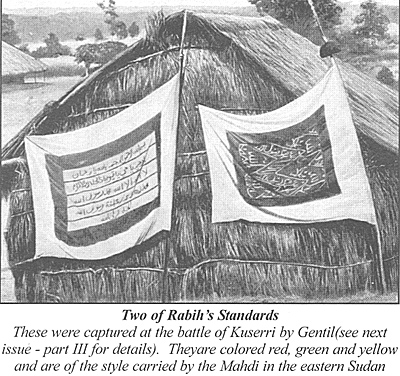

There is little information on the standards of Rabih’s army, but that they carried banners is certain from the fact that the organizational companies of troops are called “banners”. Given that at least after the 1885, Rabih was riding nominally in the name of the Mahdi, it is quite likely the he was carrying his standards. This appears to be confirmed by this photograph taken after Kusseri where two of the Rabih’s standards were captured.

Order of Battle

The table lists the organization of the banner troops of Rabih’s army. There is no such organizational list for the ever-changing hoards of auxiliaries.

Part Two: Organization of the Banners (very slow: 212K)

There were other armed contingents within Rabih’s army that were not termed Banners but held quasi military functions although probably not armed with firearms. These auxiliary units were raised locally as situations warranted. Many of the small chiefdoms would ally themselves to Rabih in order to break their vassalage to the Sultans on whom Rabih had declared war. At Dikwa, these numbers grew very large and Rabih began training large contingents of archers to supplement the firepower of the bazingers. Here he also began building up the numbers of his spear-armed cavalry, as was the central Sudan tradition. A special unit worthy of mention was an auxiliary unit of 200 warriors armed with the Ngario; an “F” shaped metal weapon with all the edges sharpened, except the base where it was held. This was used in tomahawk fashion. Logone provided more than 1000 auxiliaries and 100 war canoes for Rabih to oppose Gentile on the Shari River in 1899.

Thus was Rabih’s army at the dawn of the French epoch in Central Africa. After Rabih was established in Dikwa, French missions began to arrive into the area. Following Crampel’s Mission, was Mission de Jean Dybowski into the Chad Basin in 1893. Treaties were entered into with the several minor Shari chiefs. From the east, missions were sent up the Niger by the French and the Royal Niger Company, a private company sponsored by the British Government. The Niger had been declared an international waterway by the Berlin conference. None of these missions made much, if any mention of Rabih, and the Europeans’ knowledge of his empire was sketchy at best, some thinking it was little more than an eastwards expansion of the Mahdist movement from the eastern Sudan. Rabih on the other hand was quite aware and somewhat concerned about the French advances into his territory. The pivotal mission was that of Emile Gentil, destined to be the instrument of Rabih’s downfall.

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 2

-

Part Two: Rise to Dominance

Part Two: Rabih's Army

Part Two: Organization of the Banners (very slow: 212K)

Part Two: Gentil's Missions 1897-1899

Part Two: Jumbo Color Illustration: Rabih's Warriors (slow: 319K)

African Warlord: Central Sudan, 1884 – 1911 Part 1

-

Part One: Battle of Nyellim Hills

Part One: A Leader Emerges

Part One: The Years Under Sulaiman

Part One: Azande Warfare

Part One: Jumbo Map of Central Sudan (slow: 116K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 88

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com