“Men of the 16. F. K.: Hold your rifles on the right side and prepare for the storm (assault)!”

German equivalent ranks: Leutnant = Lieutenant, Oberleutnant =1st Lieutenant, Hauptmann = Captain, Major = Major, Oberstleutnant = Lieutenant Colonel.

Armed with only obsolete black powder M71 Mausers, but possessing faith in their commander, the outnumbered 16. F.K. swept out of their protected positions into the Indian soldiers of the 101st Grenadier Battalion.

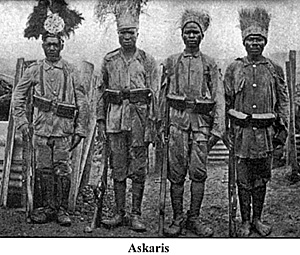

F.K. is the abbreviation for Feldkompagnie (Field Company). Feldkompagnien-an authorized feldkompanie consisted of a Europeans of one hauptmann, two leutnants, one arzt (doctor), one sanitaetsunterofficier, and two to three unteroffiziere. The native troops consisted of one sol (feldwebel), three betschausch (sergeants), seven schausch (unteroffiziere), eleven ombascha (gefrieter/corporals), and 134 askari. To this establishment was added six signallers, 40 to 60 armed machine gun bearers, and up to 200 ordinary porters. A feldkompanie could have from two to four machineguns that were provided mobility and protection by 40 to 60 armed elite machinegun porters.

This was the pivotal moment that changed the course of the battle that would prolong hostilities in East Africa for four, long years. The Battle of Tanga not only was to have a deep impact on the morale of the troops and settlers on both sides, but it also decided Lettow-Vorbeck’s dominant position in dictating the fate of German East Africa.

There were no pre-war plans for conflict between the colonies in Africa until the late summer of 1914. It was hoped that the European conflict would not extend into the African colonies as the Congo Act of 1885 contained provisions for neutralising African territories during a European war. The Germans in German East Africa split between two parties regarding adhering to the Congo Act. One group, led by Governor Heinrich von Schnee, fearing native rebellions, attempted to protect settlers’ property by proposing to negotiate peacefully with the surrounding enemy colonies. In the worst case, the schutztruppe [general term for combat troops] was to retreat to the interior of the colony in order to put up a rather symbolic resistance.

The second group, led by Oberstleutnant Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, proposed fighting with the objective of luring as many enemy troops as possible into the colony. In this way the colony could make a contribution to the war effort in Europe regardless of the cost in lives and property. After a chain of events in August 1914, which included the British naval bombardment of the wireless station at Daressalaam on 8 August and the German occupation of Taveta on 15 August, it became obvious that adhering to the Congo Act was not an option. Even so, Governor Schnee and Orbersleutnant von Lettow-Vorbeck issued contradictory orders and disputed who was in overall command.

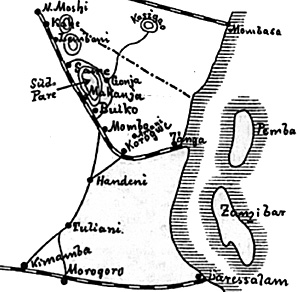

The German East Africa colony was nearly twice the size of Imperial Germany, with a total coastline of 780 kilometers. Administration of the native population of approximately 8 million people belonging to 150 different tribes was difficult. There were fewer than 6,000 Germans living in Tanganyika along the coast or in the fertile Kilimanjaro district in 1914, including women and children. The largest settlements in the colony were connected by telegraph lines and there were several small steamers operating on the lakes. The colony, however, showed a remarkable capacity to produce resources needed for a prolonged military resistance. The Biological and Agricultural Research Institute (“Amani”) in the Usumbara Mountains produced medical supplies and a number of substitutes for imported products. In addition to local production, huge amounts of supplies had been stockpiled at Daressalaam months before the war in preparation for an exposition scheduled to open on 15 August 1914. It was to demonstrate the economic development of the colony to prominent guests from Europe. The stock of 250kg of quinine proved to be most valuable in reducing non-battle casualties from malaria.

The colony possessed two main railroads that ran east to west. The “Zentralbahn” connected Daressalaam with Kigoma at Lake Tanganyika and the “Usambarabahn” connected Tanga with Moschi. The missing lines of communication from north to south were established using all available means of transport-narrow gauge plantation railroads, a handful of lorries and motor cars, and tens of thousands of native porters. It was the northern “Usambarabahn” with its 11 locomotives and 160 rail cars that proved to be a decisive factor during the Battle of Tanga. The best of the schutztruppe companies had been in the Kilimanjaro area and these companies were transported on this railroad from Mosche to Kange Station in 12-14 hours.

When war broke out, the DOAL (“Deutsche Ostafrika Linie”) had the steamers Tabora (8,022 tons) and Feldmarschall (6,182 tons) entering Daressalaam. The Feldmarschall carried some motor cars in addition to different kinds of provisions.

Another DOAL steamer, Markgraf (3,758 tons) entered Tanga harbor with a load of Indian rice. The steamer Prasident (3,335 tons) reached Lindi harbor safely from Portuguese East Africa. The light cruiser Konigsberg captured the British steamer City of Winchester and met the German steamers Ziethen and Ostmark. The Ziethen had a 100-man crew of the navy survey ship Planet on board, which reinforced the ranks of the schutztruppe along with the 102-man crew of the Moewe that was blown up in the Daressalaam harbor.

The Schutztruppe itself consisted of 220 Germans and 2,472 askari. It was divided into 14 regular companies consisting of 162 askari, 12 to 18 German officers and NCOs, and 40 to 60 rifle-armed machine gun porters each. The schutztruppe were supported by the paramilitary “polizeitruppe”.

These two organisations were supported by European volunteer militias and a small number of Boer settlers that were converted into “schuetzenkompagnien”. The armament at the beginning of the conflict consisted of 1,415 modern K98 rifles and 55 machine guns with 1.1 million cartridges. There were also 10,507 M71 rifles with 3.7 million rounds. The artillery consisted of fifteen 3.7cm guns with 3,000 shells, two 4.7cm guns with 1,000 shells, two 6cm guns with 250 shells, and seven C73 field guns with 2,500 shells. There was also available a single airplane, piloted by Oberleutnant Henneberg, that was lost in an accident on 15 November 1914.

By the time of the Battle of Tanga, approximately 1,000 askari reservists and 1,500 German reservists had been recruited. Six new feldkompagnien were formed. Four of these were by former police askari, and the number of Germans in each company was increased to 15 to 18. The remaining German reservists were formed into Schuetzenkompagnien that were entirely European at the beginning of the war and rarely exceeded a strength of 75 men in each company. These formations gradually transformed into regular askari field companies. A 400 strong Arab volunteer corps was also formed at this time.

Five thousand Europeans lived in the East African Protectorate (Kenya) in August, 1914. Interestingly, there were also 5,336 British counted as living in German East Africa at the outbreak of the war. However, there were only 3,000 Europeans of military age in Uganda and Kenya. There were no reserves of arms or ammunition available and no supply or transport arrangements except for the Jubaland Expedition. There was no headquarters staff to conduct military operations and no attempt to collect information on German movements. The only railroad was the Uganda Railroad that connected Nairobi with Kisumi.

The British navy dispatched a squadron under Captain Drury-Lowe consisting of the Chatham, Dartmouth, and Weymouth to intercept any DOAL steamers and to hunt down the Konigsberg after she sank the Pegasus on 20 September. The presence of the Konigsberg would have a strong influence on the decision to invade Tanga rather than Daressalaam.

At the outbreak of the war, the Kings African Rifles (KAR) constituted the main combat element of the British protectorates. The KAR consisted of three battalions composed of twenty infantry companies varying in strength from 75 to 125 askaris and a camel company. It totalled 70 British officers, 3 British NCOs, and 2.325 ranks. The 1st Battalion KAR, with its headquarters in Zomba, Nyasaland, had four Nyasaland companies (75 men each) and four companies of the East Africa Protectorate (100 men each). The 3rd Battalion located its headquarters at Nairobi, Kenya, with five companies and a camel company, each of 125 men. The 4th Battalion located its headquarters at Bombo, Uganda, and possessed seven companies each of 125 men.

There was no artillery, but each company had one machine gun. There were also no reserves, but there existed several unrecognised European militia and regular units. To make matters worse, six companies of the KAR were on campaign in Jubaland when the war broke out, spreading the British defensive force very thin.

Schutztruppe Deutsch Ostafrika The Battle of Tanga, November 1914

"Die 16. Feldkompanie das Gewehr zum Sturm rechts!” shouted Oberleutnant von Brandis as he stood up in full view of his wavering former polizeitruppen [police troops].

"Die 16. Feldkompanie das Gewehr zum Sturm rechts!” shouted Oberleutnant von Brandis as he stood up in full view of his wavering former polizeitruppen [police troops].

BACKGROUND

German East Africa

The police force consisted of 45 Europeans and 2,540 police askari. In addition there was a number of “knuppel-askari”. These were auxillery askari armed with only a stick. “Knuppel” means “thick stick” in German.

The police force consisted of 45 Europeans and 2,540 police askari. In addition there was a number of “knuppel-askari”. These were auxillery askari armed with only a stick. “Knuppel” means “thick stick” in German.

British Colonies of Kenya and Uganda

Background

Preliminaries

Tanga

Preparation for Battle

The Battle: Nov. 4, 1914

Denouement: Nov. 5-6, 1914

Tabletop Tanga: Wargaming the Battle

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #86

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com