On the day after the battle, 18 September, McClellan was willing

to let his forces sit in place. Lee, on the other hand, continued to look

for a chance to counterattack. Only slowly were his lieutenants able to

convince him that such a stroke simply courted disaster. At last orders

were given for withdrawal into Virginia, and the trains began to move to

the rear. After dark, the infantry began a quiet, unhindered withdrawal.

On the day after the battle, 18 September, McClellan was willing

to let his forces sit in place. Lee, on the other hand, continued to look

for a chance to counterattack. Only slowly were his lieutenants able to

convince him that such a stroke simply courted disaster. At last orders

were given for withdrawal into Virginia, and the trains began to move to

the rear. After dark, the infantry began a quiet, unhindered withdrawal.

The crossing of the Potomac was a slow business, completed only early on 19 September. On the same morning Pleasonton's cavalry and Porter's V Corps began to pursue the retreating Confederates. Lee's vanguard was in Martinsburg by the time the Federals encountered his rearguard at Boteler's Ford. Porter sent a probing force across the river, which captured some Southern guns.

In a panic, Chief of Artillery Pendleton appealed to Lee for help. A.P. Hill was sent back too late to recover the guns. Hill did arrive in time to maul the raw 118th Pennsylvania volunteers, the so-called Corn Exchange regiment, which belonged to another probing force. This unit's commander had rashly failed to retreat when Porter's other troops withdrew back across the Potomac. (These hapless volunteers were further cursed with shoddy rifles, bought in Europe to equip the ever- expanding Union host.) After this fight, McClellan let Lee retreat unmolested.

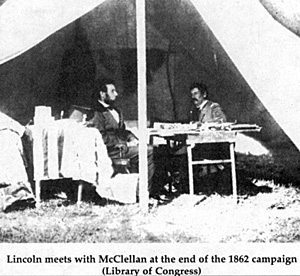

After spending a month boasting of his victory and calling for more men, McClellan finally attempted an offensive movement into Virginia. When Lee moved to block him, McClellan readily gave up all thought of further action. Lincoln bitterly complained that the Army of the Potomac had become nothing more than McClellan's bodyguard.

Moved by this abortive campaign, by Stuart's successful raid as far as Chambersburg, PA, and by fears that the "Young Napoleon" had political ambitions, Lincoln decided to name a new commander of the Army of the Potomac. On 5 November 1862, McClellan was ordered to turn over his command to Burnside. Although the new commander was keenly aware of his own failings, he felt obliged to comply with orders.

It remained to be seen, however, whether the Army of the Potomac would accept the appointment. At first it seemed as if it would not. News of Lincoln's decision hit the Army of the Potomac like a thunderbolt. Officers talked of marching on Washington to oust the scoundrels in office there. Men in the ranks wept openly at the thought of losing their leader. Despite these emotional displays by officers and men, McClellan departed the army for a short-lived political career and a long period of literary effort, writing and rewriting his memoirs in a vain effort to salvage a tarnished reputation. Only a certain element in the Army of the Potomac would continue to believe that the "Young Napoleon" had been wronged.

Officers as different as the dashing George Armstrong Custer and the priggish Marsena. Patrick would remain alert to rumors that "Mac" was back. The rest of the army learned to soldier on under Burnside, Hooker, and Meade, with diminished enthusiasm for new leadership but a dogged devotion to duty.

McClellan had a great deal to explain away in his memoirs. Throughout the Sharpsburg campaign, except when holding Lee's plan of campaign in his hand, his leadership was hesitant. On the field of battle, McClellan made little effort to coordinate his attack. Burnside was left idle, while Hooker attacked. Mansfield and Sumner were allowed to commit their corps separately. When Burnside did attack, little effort was made to help him. Franklin's and Porter's men were allowed to sit idle while the chance to win the war in a day was thrown away. In McClellan's eyes everyone, especially Burnside, was at fault. Later historians would reach a different conclusion, that, whatever the failings of McClellan's lieutenants, he served them worse than they served him. The Army of the Potomac fought bravely but with one arm tied behind its back by its own commander.

Lee, in contrast, was ever bold, even rash. The operation against Harpers Ferry was predicated on a contemptuous view of the opposing commander. Only when the Lost Order was in his hand, however, did McClellan fail to act exactly as his opponent expected.

Lee displayed, moreover, sound judgment of men and of terrain. South Mountain was used well as a shield, and maximum use was made of the advantages offered by the bridges and fords over Antietam Creek, of the embankments along its course, of the woods and eminences west of the stream. The Confederate divisions were assigned where they were needed, each emergency being detected in time to remedy its effects. Lee's handling of reserves, except for the accidental havoc wrought by Pryor's blundering use of Anderson's men, was excellent. Small wonder that Lee would remain the most feared of Confederate commanders during the war, becoming nominal general in chief.

After the war, when it became necessary to choose a Confederate hero to symbolize the reunification of the nation, Lee came to be admired in the North as well as the South.

But what of the results of Lee's first offensive? Seen in the short range, it achieved a limited success. Harpers Ferry was taken, and the war was carried on outside of Virginia for a few weeks. On the strategic level, however, the Maryland Campaign was an omen of disasters to come. The deadly peril created by the finding of the Lost Order was overcome, but the costs in casualties to fight a stalemated battle around Sharpsburg were high. The Confederacy was bleeding itself in attack as in defense, losing men it could ill afford.

More immediately, the stalemate at Sharpsburg looked sufficiently like a Union victory for Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation (22 September 1862). Thereafter, the Union was able to gut the plantation economy of much of the South and to recruit regiments of free blacks to fight and to provide garrisons. The European friends of the Confederacy, moreover, were effectively muzzled, since no government was willing openly to declare itself a friend of slavery.

Although McClellan had been unable to win the victory he had hoped to gain, Lincoln was able to win a decisive political victory on the basis of a drawn battle. Eventually, Lincoln would find a winning team of generals able to wear down Lee's army while they dismembered the rest of the Confederacy.

Lee's First Offensive The Maryland Campaign of 1862

- Introduction

Harper's Ferry

Battle of Antietam: Union Attack

Antietam: Fortune Favors the Confederates

After the Battle

George Sears Greene: Profile (very slow: 211K)

Lee's Invasions: Jumbo Map (extremely slow: 326K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com