Although these forays were repulsed with heavy losses, they

slowed the Union attack, buying valuable time. Brooke's entire brigade,

the last of Richardson's men, was kept busy looking off to its right,

when a decisive stroke might have been launched straight ahead. Other

counterattacks were aimed at Caldwell's brigade. Col. Edward Cross, of

the 5th New Hampshire in that brigade, distinguished himself in this

action by having his men paint themselves with burnt powder and

answer Rebel yells with Indian war whoops, as they went into action

in defense of Caldwell's left.

Although these forays were repulsed with heavy losses, they

slowed the Union attack, buying valuable time. Brooke's entire brigade,

the last of Richardson's men, was kept busy looking off to its right,

when a decisive stroke might have been launched straight ahead. Other

counterattacks were aimed at Caldwell's brigade. Col. Edward Cross, of

the 5th New Hampshire in that brigade, distinguished himself in this

action by having his men paint themselves with burnt powder and

answer Rebel yells with Indian war whoops, as they went into action

in defense of Caldwell's left.

Fortune, however, favored the Confederates. The fire of their artillery was such that Richardson was forced to pull back his men for regrouping, and he sent for artillery to deal with the Confederate guns. As the Federal guns went into position, a shell mortally wounded Richardson; Cross and Barlow also fell wounded. With these hard- driving officers removed from the field, the fire went out of this Union offensive. Longstreet was able to rebuild his defensive line to the rear of the Sunken Road, which remained in Federal hands, before Winfield Scott Hancock arrived to take charge of Richardson's division. Even Hancock "the Superb" could not launch a decisive stroke without fresh troops to commit to the fray.

At this point, as so often in the Battle of Sharpsburg, victory was within McClellan's grasp, but he let the opportunity slip by. Franklin's VI Corps arrived on the field, and its commander was ordered to take his fresh troops to the Union right. Franklin, smelling victory, was ready to send his two divisions into battle.

At that moment, Lee had no unwearied soldiers to use against such an assault. "Bull" Sumner, however, was the senior officer on the Federal right. Shaken by his experience in the West Wood, Sumner insisted that Franklin's fresh forces be used to shore up his defensive perimeter near the Miller farm.

To this point, McClellan had been content to remain a spectator, watching the battle from his headquarters east of Antietam Creek. Intervening at last, he rode to the right, arriving in time to side with Sumner in his refusal to commit Franklin's men to a thrust at the Confederate left. Only one brigade of VI Corps would see action, when its drunken commander unwisely ordered an unsupported attack on the enemy lines. As the afternoon wore on, the focus of the battle shifted away southward.

On the Federal left, the early hours had been quiet ones. First McClellan had been slow to order an attack, then Burnside and Cox, who remained in command of IX Corps, had been slow to act on orders received.

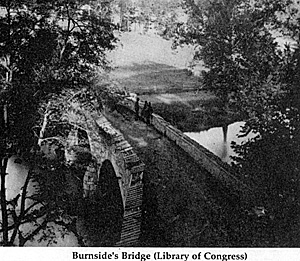

Burnside's Bridge

At last, Burnside chose the Lower Bridge as his objective and, at about 10 a.m., the attack began. Crook's brigade of the Kanahwa Division tried to approach the bridge but was driven northward by heavy fire. Then Sturgis' division was committed to the attack. Duryea's brigade was badly cut up in the first assault. Ferrero's brigade was committed next.

To secure best cooperation from his troops, this officer, once a dancing master in New York, agreed to restore the 51st Pennsylvania (Col. John Hartanft) its whiskey ration. This unit, together with its twin, the 51 st New York (Col. Robert Potter) rushed the bridge. For one of the few times in the battle, fortune favored the Union. At about the moment of Ferrero's attack, Toombs' brigade was running out of ammunition and its temporary commander, Col. "Old Rock" Benning, found that his right was being turned. (Rodman's division, which had set off exploring at about 10 a.m., had found itself a ford south of the brigade.)

Toombs' men were forced to give way, rallying on the high ground south of Sharpsburg. Rodman's men moved north from their ford, while Sturgis' and Wilcox's filed across the Lower Bridge. At about the same time, Crook's brigade found a ford north of that span and crossed to the west bank of the Antietam.

At about 3 p.m., as Crook closed from the right and Rodman from the left, Burnside was able to launch an attack toward Sharpsburg. D.R. Jones' weak division, some 2,400 men, was forced to fall back against this assault. Victory seemed to be within Burnside's grasp. Even McClellan seemed to be sending aid; two brigades of Sykes' division and the cavalry were across the Antietam. Only "Shanks" Evans' brigade stood between Sykes and Sharpsburg. Then, the consequences of delay were visited

Early in the morning, Lee had ordered A.P. Hill to bring up the Light Division from Harpers Ferry. Hill responded by leaving one brigade to parole prisoners and putting the other five on the road toward Sharpsburg. Hill's men were certain a fight was in prospect, because their commander had put on his red battle shirt. After a long, fatiguing march, the Light Division reached the battlefield.

By an accident of timing, Hill arrived as Burnside's men were moving on Sharpsburg with their left flank unprotected. (Lee, watching Jones' men retreat, spotted Hill's column arriving. He had to borrow a telescope from a nearby artillery officer to assure himself those were Southern, not Northern, appearing on his endangered right.) A rapidly devised attack caught Rodman's division unaware and shattered it. Rodman fell, one more name in Sharpsburg's book of the dead. The rest of IX Corps gave way. Cox fed in reserves to cover his men's flight to the rear, but he could not reverse the effects of Hill's attack. By 4:30, IX Corps was back near the Antietam, hemmed in by the divisions of Hill and Jones.

McClellan made no effort to revive Burnside's attack. Sykes' regulars and their cavalry support were pulled back into a defensive perimeter west of the Middle Bridge. Fitzjohn Porter urged an all too willing McClellan to retain the rest of V Corps in reserve to support the Reserve Artillery. (This counsel of caution left the "Young Napoleon" in the situation of his namesake, whose unwillingness to commit reserves at the last hour of Borodino cost him his chance for victory and ultimately his empire.)

In contrast to this caution, Lee's attitude was one of hope. He ordered an attack made on the Union right flank. Stuart scraped together a mixed force of all arms and moved out. Stuart's men retreated when an artillery concentration, built up by Meade against any such threat to his right, opened a thunderous cannonade. Even so feeble an effort, however, helped McClellan convince himself that he should not make one last effort to gain a decisive victory.

As night closed on the battlefield around Sharpsburg, some 25,000 men lay dead or wounded. Some of the wounded, among them young Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., would live to fight again and lead full lives in a post-war world. Others would die of mortal wounds, perish from infection or live permanently mutilated by the surgeon's knife.

This butcher bill further served to undermine McClellan's will to fight. Even the arrival of Couch's laggard division and of a fresh division of 9-month troops under Andrew A. Humphreys did not seem to be enough reinforcements for the "Young Napoleon." (McClellan would even try to blame his own hesitation on Humphreys' "late" arrival, but that able officer would force his erstwhile commander to retract this charge.)

Lee's First Offensive The Maryland Campaign of 1862

- Introduction

Harper's Ferry

Battle of Antietam: Union Attack

Antietam: Fortune Favors the Confederates

After the Battle

George Sears Greene: Profile (very slow: 211K)

Lee's Invasions: Jumbo Map (extremely slow: 326K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com