In September 1862, Robert E. Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis that

he had decided to undertake offensive operations north of the Potomac.

Until that month Confederate forces in Virginia had stood on the

strategic defensive, repelling successive Union invasions. The Potomac

valley and northwest counties had been occupied by Federal forces

since the early months of the war. The northwest counties had been

detached from Virginia with the cooperation of the inhabitants, later to

become the state of West Virginia.

In September 1862, Robert E. Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis that

he had decided to undertake offensive operations north of the Potomac.

Until that month Confederate forces in Virginia had stood on the

strategic defensive, repelling successive Union invasions. The Potomac

valley and northwest counties had been occupied by Federal forces

since the early months of the war. The northwest counties had been

detached from Virginia with the cooperation of the inhabitants, later to

become the state of West Virginia.

Other counties, including those between Fortress Monroe and Richmond, had experienced the devastation of invasion and combat as the scenes of campaigns by Union armies under M Dowell, McClellan, and Pope. Despite victories won by Southern armies at First Manassas, Ball's Bluff, the Seven Days Battles and Second Manassas, this was the first effort of the Confederate army to carry the war into the Northern states.

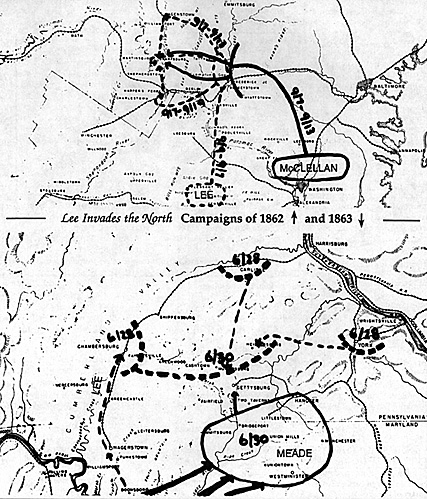

Lee's victories over Pope's Army of Virginia at Second Manassas (29-30 August) and at Chantilly (1 September) placed the Army of Northern Virginia due west of Washington. Nearby lay crossings into Maryland, where Southern sympathizers might be expected to flock to the Confederate colors. Rich forage could also be found in the untouched croplands of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Lee had no immediate intention of attacking the great concentrations of Federal troops around Washington; he contemplated striking toward the vital railroad crossings at Harrisburg, PA.

Thereafter, a blow toward Baltimore or even toward the Federal capital might become possible. (Although no such plan was mentioned to President Davis, John G. Walker, commander of a division newly added to the Army of Northern Virginia, later would report that Lee suggested such a possibility to him.) Moreover, another Confederate victory might place Lincoln's Republican administration in deep political difficulties. At the very least, Virginia might be spared the further terror and devastation of war. In sum, both military and political reasons adequately supported Lee's decision to undertake his first strategic offensive.

On 3 September, orders were given to move the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac. The next day saw Lee's lean, ragged columns crossing at White's and Cheek's Fords. Despite the arrival of reinforcements from Richmond, including the two brigades of Walker's division, the rapid movement prevented full replacement of officers and men lost in the campaign against Pope. Brigades often were no stronger than regiments were supposed to be, and many were led by senior colonels in place of wounded brigadiers.

Thus some 50,000 soldiers undertook this offensive. Almost immediately, their ranks began to be thinned by the effects of sun, sore feet, and diarrhea. Any hope of replacing these losses with recruits enrolled in Maryland dimmed. Southern sympathizers were quick to wave flags and offer refreshments, but few, perhaps 200 in all, enlisted. (Not all of the residents of Frederick were waving Confederate flags, some waved the Stars and Stripes. One woman pinned Old Glory to her bodice, which caused one Southerner to quip that Confederate troops were used to assaulting breastworks.

It was on this sort of material that the poet Whittier built his legend of ancient Barbara Fritchie being saved by Stonewall Jackson from the fatal consequences of waving the Union colors at Confederate troops.)

While the Confederates concentrated at Frederick, MD (7 September), Lee had to plan the next step in his campaign. Among the factors Lee had to consider were the dwindling stocks of supplies available around Frederick and the vulnerability of his line of communications, which ran southward across the Potomac, temptingly near the Union forces concentrated around Washington.

On 9 September, Lee issued Special Order 191, which proposed a bold stroke against the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry, capture of which would secure necessary supplies and open a line of communications to the Shenandoah Valley. This plan was conditioned by the geography of western Maryland. Harpers Ferry, once the site of a vast arsenal complex, lay on a tongue of land at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers.

There the rivers merged, and the Potomac continued in a southeastward direction through the eastern ridges of the Appalachian Mountains into the open lands surrounding Washington. Lee's army could use South Mountain, the Appalachian ridge nearest Frederick, as a screen against the Federal army while it enveloped Harpers Ferry from all sides. As the first stage of this envelopment, Walker's division was to recross the Potomac and move on Harpers Ferry from the southeast. McLaws' and Anderson's divisions were to move westward across South Mountain at Crampton's Cap and to close on Harpers Ferry from the northeast.

The remainder of the army was to cross at Turner's Gap. Thereafter, Jackson would move southwestward with three divisions, those of J.R. Jones, A.R. Lawton, and A.P. Hill, to Williamsport, MD, where he was to cross the Potomac and complete the envelopment of Harpers Ferry by moving in from the west. Longstreet would move his two divisions, those of Hood and D.R. Jones, toward Boonsborough, MD, with D.H. Hill's division following behind. Stuart's cavalry would remain behind to picket the passes through South Mountain. After the capture of Harpers Ferry, the whole army was to assemble at Boonsborough or at nearby Hagerstown to resume its northward march. The whole maneuver was predicated on the Union army's displaying its usual inertia. On 10 September, the Confederate columns stepped out smartly toward their objectives.

Union Reaction

The Confederate invasion of Maryland caused consternation in Washington. President Lincoln was to complain that the entire War Department went into a state of paralysis. Although this complaint is not entirely fair, General in Chief Halleck seemed unable to take positive action - or even to comprehend the perilous position of the garrison at Harpers Ferry. (His suggestion that garrison commander Col. Dixon Miles move his forces to waterless Maryland Heights, the objective of McLaws'Confederate column, was less than helpful.)

On 2 September 1862, George B. McClellan, creator of the Army of the Potomac, had been given command of the forces gathered around Washington. His return to the field heartened the veterans of his own and Pope's battered armies, who seemed to hold their commander in awe. (A few days later Pope was relieved of all command responsibilities, eventually to be banished to a job fighting Indians in the northern Plains region.) The "Young Napoleon," however, was as slow as ever to move before everything was in perfect order, and he remained convinced he was outnumbered by odds as high as two to one.

At last, McClellan detached two battered corps (III and XI) under Nathaniel Banks to protect Washington. Then he started the renewed Army of the Potomac toward Frederick, MD. The left wing (VI Corps, Sykes' division of V Corps and Couch's division of IV Corps) under William B. Franklin marched near the Potomac. The center (II Corps and XII Corps), under Edwin V. Sumner, followed the National Road to Frederick.

The right (I Corps and IX Corps), under Ambrose E. Burnside, followed the line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Pleasonton's cavalry division screened the slow advance of these columns, while Morrell's division of V Corps and the reserve artillery trailed behind. By the time the Union army closed on Frederick (12 September), however, Lee's army had been gone for two days. McClellan's slow movements seemed, to that date, to augur well for the success of Lee's attack on Harpers Ferry.

Lee's First Offensive The Maryland Campaign of 1862

- Introduction

Harper's Ferry

Battle of Antietam: Union Attack

Antietam: Fortune Favors the Confederates

After the Battle

George Sears Greene: Profile (very slow: 211K)

Lee's Invasions: Jumbo Map (extremely slow: 326K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 2

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com