The Algerian campaign of 1956 was executed with renewed energy by the troops under Salan. With the new reinforcements the French emplaced their quadrillage system. Then the French sought to limit external support for the FLN. Much of this external support had been coming from Egypt, and when the Egyptian leader Nasser took over control of the Suez Canal, which had been controlled by a Franco-British company, the French determined to move against the Egyptians.

It was hoped that the example of the Egyptians would serve to dissuade other nations from lending support to the FLN. In cooperation with the British, the French moved their forces earmarked for the Egyptian operation to bases in Cyprus, where they joined the British contingent. The French contingent was composed of the 10th Parachute Division (General Jacques Massu) with four regiments, and a brigade of the 7th Mechanized Division, along with five other battalions.

These units spent the months from August to October 1956 in the Cyprus staging areas. In November the Franco-British forces moved against Egypt, invading Port Said at the Mediterranean end of the Suez Canal. But the invasion turned out to be a major diplomatic blunder by the French and British, who were threatened by both the Soviets and the United States. French units pulled out of Egypt in late November 1956 and were redeployed in Algeria by December. The example of the Egyptians, as it turned out, would certainly not dissuade other nations from aid to the FLN.

In the meantime, the increasing ALN efforts in the Algerian cities were bearing fruit. By early 1957 the ALIN had substantial strength in Algiers, and had also made inroads in the other major city, Oran. On 16 January there was an ALN attempt to kill Salan. A bazooka was fired at him as he emerged from the Government General building. Salan escaped, but the fact that such an attempt had been possible was a disturbing indication of ALN strength.

Hitherto the cities had been the exclusive province of the police. Except for propaganda and information purposes the Army stayed clear of the whole situation. However, on 15 January 1957, the day preceding the attempt, the government had agreed to impose martial law in Algiers.

The operation, designed 'Champagne,' began on the night of 25/26 January 1957 when Massi's 10th Paratroop Division moved into Algiers in trucks. The division's four regiments (1st, 2nd, and 3rd Colonial Parachute along with the 1st REP) numbered together perhaps 5,000 troops. The Algiers population ran to about 250,000 and recent estimates of ALN strength stood at 200 terrorists and 5,000 FLN members. But the paratroops were determined to succeed, would go to any lengths to do so, and were prepared to utilize all information on immediate raids. Thus, when the people of Algiers woke up in the morning of 26 January, they 'discovered they were living in a new town.'

The 10th Parachute Division manned the barricades around the Casbah and issued new identification cards to the entire population, Random day and night searches were instituted and anyone who resisted was shot. Thousands of prisoners were taken to secret places for interrogation. A virtual police state was imposed on Algiers.

Between February and April the FLN organization was badly decimated, but by June the FLN had recovered much of its lost ground. In a final phase of the battle though, lasting from June to October, the FLN leaders were tracked down and eliminated and their organization was finally smashed.

Many Frenchmen have since claimed that the Battle of Algiers represented the greatest French victory of the Algerian War. Those on the FLN side have claimed that Algiers assured the victory of the FLN. On balance, it appears that the Algerians are the more correct.

A primary tenet of military doctrines dealing with counterinsurgency is that victory in the war depends upon convincing the population that the counterinsurgents are 'better' than the guerrillas and therefore worthy of the loyalty of the people.

For the French in Algeria, who could not offer independence to the Algerians and therefore could not claim to be politically 'better' than the FLN, this meant that the French had to treat Algerians 'better' than the FLN. But the methods used by the paratroops in Algiers proved to be a concrete example which the FLN could cite to show how French claims of 'better' treatment were fictitious. After the Battle of Algiers only avenues involving the use of pure military force were available to the French.

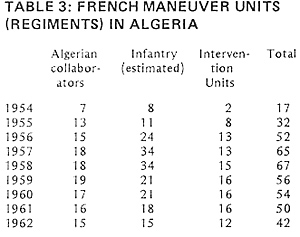

Consequently, it was in 1957 and 1958, that the French reached their peak level of war effort in Algeria. While the number of Algerian units were still stable, French infantry strength was beginning to erode. In 1958 the Army, dissatisfied with the government's failure to prosecute the war with determination, launched a revolt in Algeria that toppled the French national government. A new government, acceptable to the Army, was formed under Charles DeGaulle. But the new government, uncomfortable with all the military power in Algeria, began to withdraw units from that area. This process was further increased after renewed military revolts in 1960 and 1961. Then DeGaulle disbanded some military units for their participation in these revolts, including three of the ten parachute regiments in Algeria.

In this context, the Battle of Algiers takes on added significance. The French had available only military solutions at a time when their military strength began to fall off. The only solution French ground commanders could see to this problem was that of increased energy in the prosecution of the war. The fact that the FLN was almost as exhausted by the war as the French were, enabled the French to maintain a slight edge in the military situation. The new French commander, General Maurice Challe, based his strategy precisely on this situation.

| TABLE 3: FRENCH MANEUVER UNITS (REGIMENTS) IN ALGERIA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Algerian Collaborators | Infantry (estimated) | Intervention Units | Total |

| 1954 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 17 |

| 1955 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 32 |

| 1956 | 15 | 24 | 13 | 52 |

| 1957 | 18 | 34 | 13 | 65 |

| 1958 | 18 | 34 | 15 | 67 |

| 1959 | 19 | 21 | 16 | 56 |

| 1960 | 17 | 21 | 16 | 54 |

| 1961 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 50 |

| 1962 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 42 |

Colonial Twilight The French War in Algeria

-

Introduction

Origins of the Algerian War

War Comes to Algiers

The Year of Mobilization

The New War Strategy

Battle of Algiers

Challe's Campaign of 1959

Jaws of Victory

Back to Campaign # 73 Table of Contents

Back to Campaign List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Donald S. Lowry

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com