The Kwantung Army was the cream of the IJA.

This was reflected in the high quality of the

units assigned and the relatively large number of

heavy supporting armor and artillery units. The basic formation of the Kwantung

Army was the infantry division.

The Kwantung Army was the cream of the IJA.

This was reflected in the high quality of the

units assigned and the relatively large number of

heavy supporting armor and artillery units. The basic formation of the Kwantung

Army was the infantry division.

From the Soviet perspective, the Treaty of Portsmouth in September 1905 left a scar on Soviet-Japanese relations. It gave the Japanese the southern half of Sakhalin Island and the southern part of the Russian-built railway in Manchuria. The Soviets were forced to live by the result of the treaty which ended the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, but always felt that they had an account to settle with the Japanese.

In 1931, as the Japanese expanded into Manchuria, the Soviets were too weak to respond. Fearing a Japanese invasion of the Soviet Far East, they briefly turned to a policy of appeasement even going as far in December 1931 as offering Tokyo a non-aggression pact.

Meanwhile, by 1932, the Soviets had begun to reinforce the Far East in response to the Japanese threat. By 1933, this force had grown to nine rifle divisions, one and a half cavalry brigades, and 300 tanks. In addition, the border had begun to be heavily fortified. With this new military strength and an improved domestic situation, the appeasement policy was suspended and a belligerent policy towards Japan was adopted.

A state of armed truce existed in the Far East as frontier incidents continued along the ill- defined border and both sides continued to build up their forces.

In 1937, the great purge in the Soviet Union began to be felt in the Red Army. Initially, the Far East Army was the least affected but it was becoming a hollow force with declining morale. This resulted in a new sense of caution in June when another incident occurred along the Amur River which appeared to be taking both sides into open confrontation verging on war. The Soviets reached an agreement calling for mutual withdrawal. But when a few days later the Japanese reoccupied the islands, the Soviets did nothing. This sign of weakness was not lost on the Japanese.

The Soviets were provided a breathing space in the Far East when in July 1937 the Japanese turned against China. The Soviets did not intervene, but did provide significant material assistance and advisors to the Chinese Nationalists in an attempt to bolster their ability to withstand the Japanese onslaught. Soviet policy was to avoid direct confrontation with the Japanese and hope to tie them up in China. The Soviets also continued to build up their forces in the Far East to deter a Japanese attack.

By 1938, the purge had spread in full force to the Far East; the extent of which was known to the Japanese. However, unlike in 1937 along the Amur, when the next test came, the Soviets were determined to meet the challenge.

This test came in July 1938 on two desolate hilltops near Lake Khasan on the border with Japanese-controlled Korea. When the Soviets initially occupied the hilltops, the Japanese counterattacked and dislodged them. The Soviets were determined to restore their version of the border and eventually assembled two divisions supported by aircraft and as many as 350 tanks to expel the Japanese.

A series of Soviet attacks between

31 July and 9 August forced the Japanese

to request a cease-fire on 11 August.

Despite the Soviets' military and political

victory, their military

performance was poor. Proper coordination of

artillery was lacking, tanks were unsupported

and proved to be at the mercy of Japanese

antitank guns (93 were lost or suffered major

damage), and tanks proved unable to support

the infantry. Lower level tactical training had

proven insufficient across the board.

A series of Soviet attacks between

31 July and 9 August forced the Japanese

to request a cease-fire on 11 August.

Despite the Soviets' military and political

victory, their military

performance was poor. Proper coordination of

artillery was lacking, tanks were unsupported

and proved to be at the mercy of Japanese

antitank guns (93 were lost or suffered major

damage), and tanks proved unable to support

the infantry. Lower level tactical training had

proven insufficient across the board.

Tensions continued into 1939 with the Soviets recording 30 infringements of the border into April. In May, as Japan's attention turned to Outer Mongolia, the stage was set for the largest clash between the Kwantung Army and the Soviets until 1945.

The Nomonhan Incident (or Battle of Khalkhin-Gol to the Soviets), previously described, was a devastating blow to the Japanese and provided them much to ponder regarding their ability to engage the Soviets. As the battle was raging in Mongolia, the Japanese received another shock--the Soviets and the Germans has signed a nonaggression pact on 23 August. Soviet military success at Nomonhan and the entente with Germany swung the balance of power in the Far East to the Soviet Union.

In June 1940, a border agreement was reached and the number of incidents was reduced significantly. In April, in the face of increasing threats from Germany, Moscow agreed to a neutrality pact with the Japanese. This agreement remained in effect until 1945 when the Soviets were finally able to even the score with the Japanese.

North Wind Rain Japanese Invasion of Manchuria

- Introduction and Background

The Nomohan Incident

Preparations for the Next Round

Japanese 1941 Campaign Plan

Into 1942 and Beyond

Kwantung Army Close Up

The Soviets Prepare

The Red Army and the Far East

The Red Army in 1942

Opposing Air Forces

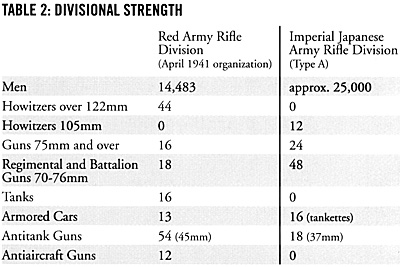

Red Army Rifle Division April 1941 TO&E

Red Army Rifle Division July 1942 TO&E

Red Army Rifle Brigade July 1942 TO&E

Red Army Tank Brigade July 1942 TO&E

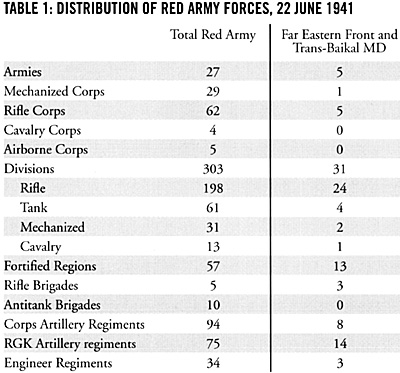

Red Army Far Eastern Front June 1941

Red Army Trans-Baikal Military District June 1941

Large Map: Kwangtung Army Deployment August 1941 (slow: 116K)

Jumbo Map: Kwangtung Army Deployment August 1941 (very slow: 397K)

Alternative History: 2nd Russo-Japanese War

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.