Throughout 1941 and 1942 two huge

armies, one Japanese and one Soviet, stood

poised to decide the fate of two empires.

Throughout 1941 and 1942 two huge

armies, one Japanese and one Soviet, stood

poised to decide the fate of two empires.

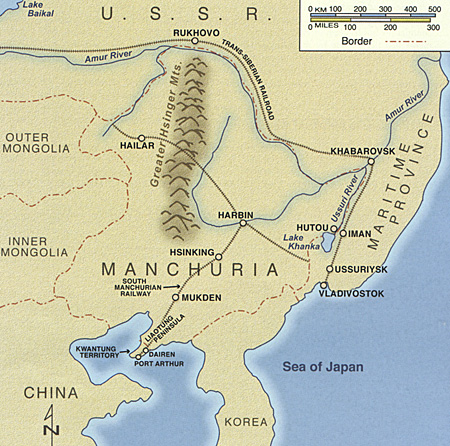

These armies constituted the cream of their respective militaries. The Japanese Kwantung Army, based in Manchuria, had long trained and planned to attack its Soviet enemy. The armies of the Soviet Far East had just fought a series of border battles with the Japanese and were braced for another inevitable Japanese attack. With the start of German invasion of Russia in June 1941, it looked all but certain that the Japanese would take the opportunity to finish off the struggling Soviets.

In the event, in spite of all expectations, the Kwantung Army would not see combat against the Soviets until August 1945, and only then when the Soviets launched a massive attack to assist in the final dismemberment if the Japanese Empire. The titanic clash between the Japanese and Soviets in 1941 and 1942 remained unfought; it would forever remain a matter of conjecture on whether or how it would have changed the outcome of the Second World War.

RISE OF THE KWANTUNG ARMY

The Kwantung Army was created in April 1919 with a strength of just over one division and charged with the protection of the Kwantung Territory and the South Manchurian Railway. The strength of the army remained unchanged until the Mukden Incident in 1931 when reinforcements were sent from Korea and the Japanese homeland. The incident, the result of plotters within the Kwantung Army, was used as a pretext to "solve" the Manchurian problem.

Within five months, the Japanese had conquered all of Manchuria and established the puppet government of Manchukuo in February 1932. The requirement to garrison Manchuria lead to an increase of the Kwantung Army to three divisions in 1933.

From 1937, in the aftermath of the

China Incident in July of that year, and as

tensions with the Soviet Union deepened, the

expansion of the Kwantung Army quickened.

By the time of the Nomonhan Incident in 1939,

there were nine divisions and a large number of

garrison units assigned. Following the

Nomonhan incident (see below), additional

units were posted to Manchuria for a total of

13 divisions and an overall strength of 350,000

men.

From 1937, in the aftermath of the

China Incident in July of that year, and as

tensions with the Soviet Union deepened, the

expansion of the Kwantung Army quickened.

By the time of the Nomonhan Incident in 1939,

there were nine divisions and a large number of

garrison units assigned. Following the

Nomonhan incident (see below), additional

units were posted to Manchuria for a total of

13 divisions and an overall strength of 350,000

men.

Up until the Pacific War, the focus of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) remained that of waging a large-scale continental war against the Soviets. Accordingly, the numbers of men and equipment allocated to the Kwantung Army represented a large portion of the IJA's total assets. This included many of the Armys best units. Even with the outbreak of war with China in 1937, the policy of maintaining a substantial segment of the IJA in Manchuria was unchanged.

The Japanese, especially after their defeat at Nomonhan, did not take the Soviets lightly as potential adversaries. The Japanese reliance on factors of morale and offensive elan was not born out of arrogance, but because Japan was too poor to afford the massive amounts of artillery and armor that would allow them to engage the Soviets on an equal footing. Even in terms of manpower, the Japanese expected to fight the Soviets at up to a 3:1 numerical disadvantage.

Against the Soviets, the Japanese would use a better-trained force employing tactics of envelopment, mobility, and close-in combat. The Japanese hoped to turn their interior lines of movement within Manchuria into the ability to quickly mass at key points. The Soviets would be unable to respond as they were hamstrung by the limited capacities of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. With local superiority, the enemy would be encircled and destroyed piecemeal. This would require that the Japanese weaken other sectors to establish local superiority in key sectors. As tactics against the Soviets developed, the Kwantung Army situation became the vanguard of all IJA thinking about the Soviets.

Events in the Far East seemed to suggest a clash sooner rather than later along the ill-defined border of Manchuria and the Soviet Union. The Japanese considered the years 1935-6 as a period of medium-scale clashes.

In 1937, an incident along the Amur River resulted in the Soviets withdrawing from two disputed islands in the river that they had seized-an action the Japanese interpreted as one of weakness. In 1938, in southeast Manchuria near the tri-border area of Korea, Manchuria, and the Soviet Union, a border conflict with modest beginnings escalated into a conflict of major proportions.

Called the Changkufeung Incident by the Japanese, it involved the Kwantung Army only indirectly as the area was defended by a division of the Korean Army. In response to the Soviet seizure of a key hill located in the disputed area, a regiment of the Japanese 19th Division ejected the Soviets. However, this time the Soviets were not going to back down. Supported by heavy air attacks, armor and artillery, the Soviets forced the Japanese to abandon the whole disputed area in midAugust.

The stage was now set for the largest clash between the Kwantung Army and the Soviet Army until 1945. It was a major lesson for the IJA in general and the Kwantung Army in particular and undoubtedly weighed on the Japanese as they debated whether to turn on the Soviets in 1941 or 1942. This clash, occurring as it did in the summer of 1939, was overshadowed by events in Europe, but epitomized on a smaller scale what would have occurred in 1941 if the contestants had returned to the field of battle.

North Wind Rain Japanese Invasion of Manchuria

- Introduction and Background

The Nomohan Incident

Preparations for the Next Round

Japanese 1941 Campaign Plan

Into 1942 and Beyond

Kwantung Army Close Up

The Soviets Prepare

The Red Army and the Far East

The Red Army in 1942

Opposing Air Forces

Red Army Rifle Division April 1941 TO&E

Red Army Rifle Division July 1942 TO&E

Red Army Rifle Brigade July 1942 TO&E

Red Army Tank Brigade July 1942 TO&E

Red Army Far Eastern Front June 1941

Red Army Trans-Baikal Military District June 1941

Large Map: Kwangtung Army Deployment August 1941 (slow: 116K)

Jumbo Map: Kwangtung Army Deployment August 1941 (very slow: 397K)

Alternative History: 2nd Russo-Japanese War

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.