By the end of the crossing, Napoleon's army had dwindled to 20,000 effective soldiers. Among the casualties, his army lost over 1,200 officers either killed or wounded and 20,000 to 25,000 men.

According to one report, some 32,000 bodies were excavated from the Berezina and its banks after the spring thaw and had to be burned there, 40% of them civilian noncombatants. The biomass of human and animal corpses and military detritus silted over with mud and eventually formed a permanent island where the bridge had stood.

Tons of booty and supplies were lost, together with 23 artillery pieces: jewelry, furs, jewels and pearls, chalices from Moscow churches, icons, rare illuminated books and manuscripts, silver, and porcelain all went into the river to be fished out in the months and years to come. The Russians in the battles at the Berezina lost over 10,000 killed, wounded, or captured. For this battle, there was no true victor. The Russian armies had performed bravely in combat, but the three leaders, Tchichagov, Wittgenstein, and Kutusov, all performed too tentatively and cautiously to hope for a better result. Tchichagov's lack of initiative coupled with Kutusov's sloth-like reactions were most to blame for the situation, although it is only in comparison to these two that Wittgenstein looks at all adequate.

Napoleon's success could squarely be laid at the feet of this trio. He even experienced further benefits when Tchichagov had not destroyed the next series of bridges at the Zembin causeway. Instead, Napoleon was able to cross the causeway even though the bridges had been prepared by the Russians to be fired. In fact, beside the bravery exhibited by troops on both sides, their leaders' actions stand in dark contrast. Napoleon's biggest success in the crossing was that he successfully escaped. Over the next weeks, his army would dwindle further.

At Smoroni on December 5th , Napoleon gathered his leaders together, placed Murat in charge of the remnants and then with Caulincourt and a small detachment of Neapolitan cavalry he headed back to Paris. His intent was to stabilize the homefront and raise a new army. Thus, the Russian Campaign had ended. The Berezina had been crossed but at a very high price.

Bibliography

The source material on Napoleon's 1812 campaign in Russia is voluminous, though most authors devote only a chapter or two specifically to the Berezina crossing. I found the sources below some of the most enlightening, but largely do tell the tale from the French perspective.

1812. Napoleon's Russian Campaign; by Richard K.

Riehn; R.R. Donnelly & Sons Company; Crawfordsville IN, 1990

1812 The Great Retreat, by Paul Britten Austin;

Stackpole Books; Mechanicsburg PA, 1996

Anatomy of Glory, The; by Henry Lachouque, Percy

Lund, Humphries and Co., Ltd; London UK; 1962

Campaigns of Napoleon, The , by David Chandler;

Macmillan Publishing Co.; New York NY; 1966

Grande Armie, La; by Georges Blond; trans. by

Marshall May; Arms and Armour Press; London UK; 1995

Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book by Digby

Smith, Stackpole Books; Mechanicsburg PA, 1998

Memoirs of Baron de Marbot Vol II The, by Baron de

Marbot, trans. by Arthur John Butler; Longmans, Green, and Co.;

London UK; 1892

Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic War A;

by Esposito and Elting; Stackpole Books; Mechanicsburg PA, 1999

Napoleon's Invasion of Russia; by George E Nafziger;

Presidio Press, Novata CA, 1988

Napoleon's Russian Campaign; by Count Philippe-Paul & Segur; trans. by J. David Townsend; Houghton Mifflin

Company; Boston MA; 1958

Napoleon's Mercenaries; by Guy C. Dempsey, Jr.;

Stackpole Books; Mechanicsburg PA, 2002

With Napoleon in Russia; by Armand de

Caulaincourt; William Morrow and Company; New York NY; 1935

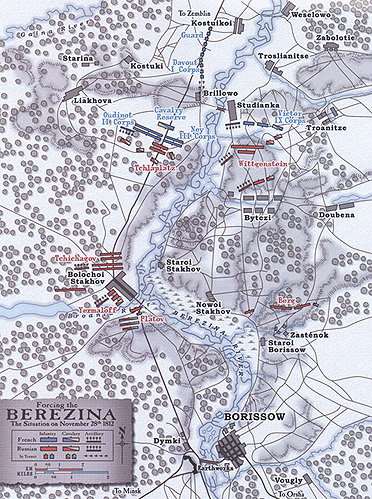

Nov. 28, 1812 Map

Napoleon at the Berezina 1812

- Background

Ney's Rearguard

Napoleon's Options

Bridging the Berezina

End of the Crossing

Gen. Claude Malet's Coup

Gen. Jean-Baptiste Eble

Large Map: November 26, 1812 (slow: 169K)

Large Map: November 27, 1812 (slow: 161K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 4

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.