At the same time, Ney approached the Krasnoe battlefield. Once again, Miloradovich had moved across the road in a blocking position. Ney had only left Smolensk on November 17. His demolition of Smolensk had been harassed at every step. When he left, there was a 20-mile gap that had developed between his force and Davout's. His force was 6,000 strong with 5,000 left behind. Following along with his force, was a swarm of stragglers that from a distance made the corps swell in size, but which actually impeded his march.

Napoleon had already written Ney off, "He will attempt the impossible and lose his life in some desperate attack. I'd give 330 million in gold to save him."

That sum would have done Ney little good, as he gazed at Miloradovich's position at 3 p.m. Kutusov was concentrating his entire force at this point. Three enemy corps closed on him from all sides. Just then, a Russian officer under flag of truce approached from Miloradovich's position, telling Ney that the emperor had abandoned him and Ney's situation called for surrender.

Ney's response was, "A marshal does not surrender!" Using some random shots from the Russian position as a breach of the truce, Ney kept the Russian prisoner. Ney feared that the officer would appraise the Russians of the actual condition of Ney's forces. Not wasting time, Ney ordered an attack and committed half of his force to the assault. It penetrated the first line only to be thrown back before it could reach the second. Kutusov, feeling that the French would surrender, failed to counterattack on either flank, or in the rear. He did not understand Ney.

As night fell, Ney assessed his situation. He could not break through the Russian position in front of him. The road back to Smolensk was equally arduous. Ney searched for a third alternative, other than surrender. Finally, he decided to move north, as had Eugene and Davout (unknown to Ney at the time). There he hoped to find a ford.

With only an ill suited map to guide him, Ney built the campfires high and slipped into the night following a stream north. When they finally reached the Dnieper, they could not find a ford. Worse, a mild turn in the weather had melted the frozen stretches of the river that Ney had hoped to use if a ford could not be found.

Ney, the gambler, seized the one opportunity that fate threw his way. At a bend in the river, drift ice had jammed together. By hopping from floe to floe, a person could cross the river. Unfortunately, as more and more people crossed the river, the distance between floes widened to the point where it was no longer possible to cross.

After 2,000 had crossed, Ney determined that the remaining 3,000 troops plus 4,000 stragglers (including women and children) had to be abandoned. No artillery or vehicles were brought across. Only a few horses swam across. The small force that had made it across then followed the river, until they reached a small village, Gusinoe.

There, after surprising a small force of Cossacks, they found food and horses. It was a mixed success, but given the situation, it was an amazing one none the less.

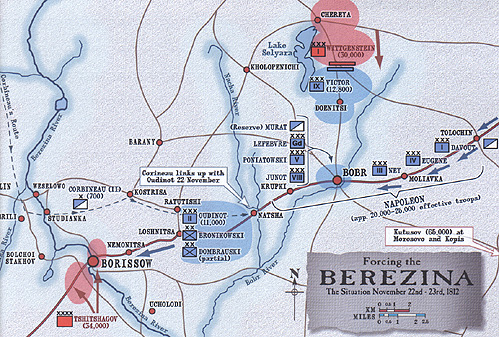

Napoleon at the Berezina 1812

- Background

Ney's Rearguard

Napoleon's Options

Bridging the Berezina

End of the Crossing

Gen. Claude Malet's Coup

Gen. Jean-Baptiste Eble

Large Map: November 26, 1812 (slow: 169K)

Large Map: November 27, 1812 (slow: 161K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 4

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.