Berezina: The name that would be etched in the memories of the French who survived it. The crossing of this river encapsulated many of the strengths and weaknesses of both armies during the retreat from Moscow.

Berezina: The name that would be etched in the memories of the French who survived it. The crossing of this river encapsulated many of the strengths and weaknesses of both armies during the retreat from Moscow.

On November 4, 1812, Napoleon and the Guard had reached Smolensk. Originally, Napoleon had hoped to make the Dneper River his winter defensive line, but, with two Russian armies advancing on his rear flanks, he began to focus on the Berezina River. Had his army been in better condition, he would have immediately set off for Borissow, the bridgehead over the Berezina. Instead, he waited as the French army straggled into Smolensk. Supply distribution fell under the heading of "first come, first serve". Chaos reigned supreme on the streets of Smolensk.

As the French army gathered at Smolensk, three Russian armies slowly moved into position to trap Napoleon. In the north, Wittgenstein moved into the gap between the Dvina and Dneper rivers with Oudinot and Victor providing some resistance. Kutusov advanced in a side southern sweep to cut the Smolensk-Orsha road. Tchichagov was threatening Minsk and its rich store of supplies. When Minsk fell (which it did on November 16), Napoleon knew that Borissow would be next on Tchichagov's agenda.

In the face of such growing anxieties, Napoleon remained calm. Each day, he rode out to inspect Smolensk's defenses, maintaining the fiction that Smolensk would be held and defended. To his troops, his demeanor was reassuring; everything was under control. Reality was, of course, much different. The Grand Army now numbered 40,000. The artillery had been reduced by 350 guns, and the cavalry was down to 3,000. There were few reinforcements expected, except the few hundred raw recruits who had arrived from France hungry and exhausted.

Finally, Napoleon resolved to move. The Guard would lead the way with Ney assuming the rearguard. Napoleon gave orders to destroy the city walls and on November 13 the French began to leave Smolensk. The state of transport had reached the point where all the wounded were left behind.

To make matters worse, winter had truly come. The gentle rolling hills the French had marched through on their way to Moscow were now sheets of ice. As each group passed over the roads, the ice became more polished and more impossible to march on. At night, some would go to sleep, never to wake again in the freezing temperatures, while others eating snow instead of drinking water would perish when the snow reached their intestines.

Further, the daylight was a short-term item of 8 hours in length. On the first day, it took the Guard 22 hours to march 15 miles.

The breakdown of order and discipline was occurring everywhere. Officers stopped trying to impose order, since the imposed order vanished the minute that the authority focused on something else. When a soldier fell from illness or exhaustion, his fellow soldiers would fall on him, stripping him of clothing and possessions, guaranteeing him of a certain death.

Horses became a source of food. With butchering of a horse too time consuming, slabs of meat would be cut from the live horse. The horse, frozen and numb from the cold would continue to walk for a while before the infection from the wound would incapacitate the animal. Quickly, the semblance of an army disappeared. In its place was an undisciplined mob, driven by the realization that to stop was to die -- either from the cold or at the hands of the Cossacks who constantly were there to cut down the stragglers.

On November 14, the retreating French encountered a force of 20,000 under Miloradovich, six miles east of the town of Krasnoe. That evening, as the French quartered in Korymia, reports reached Napoleon of the Russian force, blocking the road. On the morning of the 15th the battle of Krasnoe (a four day running battle) would begin. Fearing himself heavily outnumbered, Miloradovich saw his role as one of skirmish rather than battle.

When Davout failed to clear the road, the Guard was brought up. Miloradovich withdrew to the flanks and began to bombard the French as they struggled through the deep gorge where Krasnoe was located. That night, Miloradovich reoccupied the road, cutting off Napoleon and the Guard from the rest of the French army which stretched forty miles along the road.

Napoleon faced a dilemma. He could continue to advance with the Guard and hopefully survive running the gauntlet, or he could turn and help reconnect with Eugene and the rest of the army.

He announced, "I have played the Emperor too long; it is time I played the general." He ordered the burning of tents and wagons, and sent General Durosnal and a small cavalry force back to open up the road.

Durosnal's attack fell into trouble as the much larger Russian force counterattacked. Retreating in good order, Durosnal's force fell back to the French force at Krasnoe. His action, however, had two very positive effects on the French fortunes. First, his actions diverted the Russians from Eugene. The Prince was able to lead his corps through deep snow to reconnect with Napoleon at Krasnoe. Second, it slowed down Kutusov, as the attack reconfirmed his assumption that the French outnumbered him, even though the reality was that his army, comprising the columns of Strogonov, Galitzin, and Miloradovicb, numbered at least 80,000.

For the rest of the 16th, skirmishes flared around Krasnoe. Napoleon waited, seeking some sign that Davout and Ney approached. On the 17th, Napoleon and Murat climbed a hill near the Smolensk road. There, appraising the situation, Napoleon decided he must take action. He would lead the Guard into action to clear the road for Murat and Ney. while Murat held Krasnoe against the van of Kutusov's army.

Napoleon, with General Rouget and 16,000 troops, advanced on the Russians blocking the road. Ignoring Cossack harassment, the Guard cleared the road until, at 4 p.m., they reached Miloradovich~'s main troops who were engaged with Davout. After some heated exchanges, Miloradovich, under orders from Kutusov, withdrew. By 7 p.m., Davout's corps had crossed the gorge and bypassed Krasnoe on the north side. Napoleon and the Guard were forced to leave the field and, with it, any reasonable hope of saving Ney.

By noon of the 18th, Napoleon and his force had reached the village of Orsha and crossed the Dnieper. Here he assembled the Old Guard and said to them, "You are witnessing the disintegration of the army. By fatal delusion, most of your brothers-inarms have given up the fight. If you follow their tragic example all is lost. The fate of the army rests with you. I know you will justify my confidence in you. Your officers must not only maintain strict discipline, but you yourselves must keep a rigorous watch over each other and punish those who try to leave the ranks. I count on you. Swear that you will not abandon your Emperor!"

The answer was "We swear!" With that, Napoleon ordered the band to play "the Song of Departure" and the march resumed.

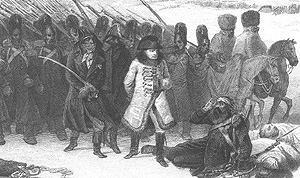

Napoleon at the Berezina 1812

- Background

Ney's Rearguard

Napoleon's Options

Bridging the Berezina

End of the Crossing

Gen. Claude Malet's Coup

Gen. Jean-Baptiste Eble

Large Map: November 26, 1812 (slow: 169K)

Large Map: November 27, 1812 (slow: 161K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 4

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.