The bombardment of Khe Sanh that night would not be so heavy by the standards of later days-- there were just a hundred rounds of mortars, most 82mm, and about sixty 122mm rockets. What made the early morning bombardment so dangerous was the target, the center and eastern quadrant of the combat base. The main ammunition dump would be hit and quickly caught fire, triggering a secondary explosion, more fires, and scattering hot shells for 105mm howitzers and 106mm recoilless rifles all over the place. Some Marine trenches were several feet deep with shells blown out of the dump, shells that themselves could cook off at any second.

Around 10 AM the fires ignited a big stockpile of C-4 plastic explosive, severely damaging the command bunker of the 1/26 Marines. Under the circumstances, Battery C of the 1/ 13 Marine Artillery were nothing less than heroic in staying at their guns, located just fifty to seventy-five yards from the exploding ammunition dump. Everything Marines tried to do became even tougher once the ammunition dump fires set off the base's entire stock of CS tear gas, which then wafted in thick clouds throughout the area. Lieutenant Colonel James B. Wilkinson, 1/26s commander, had been warned the People's Army had gas and had then ordered his men to have masks on hand.

The morning of January 21 even having gas masks would not be enough the stuff was so thick. Some of the most famous photographs of Khe Sanh would be those taken of the scene around the ammunition dump that day.

Not much more than an hour or two following the bombardment of Khe Sanh Combat Base, the surrounding hamlets and Khe Sanh village, home to the Marines' Combined Action Company Oscar, a regional force company, and district troops, sustained a major attack. A couple of days before, Major Bruce B. G. Clark had been on patrol with some of the district forces when the Green Berets at Lang Vei asked him to clear the area.

B-52s

Shortly afterwards the sector was hit by B-52s in an ARC LIGHT strike. This proved inadequate to fend off the attack of January 21, however. Clark, the district senior advisor, had just begun taking out another patrol, a platoon of Bru tribesmen with the Combined Action Company, when the assault commenced. A battalion of the 66th Regiment of the People's Army 304th Division would be the main attack force. It was a unit the spooks of the National Security Agency had not succeeded in locating.

Major Clark and the Combined Action Company held out through the day, assisted by massive artillery support, including a barrage of morel* than a thousand rounds with variable time fuses, plus much close air support. Late in the afternoon a relief attempt was made-- Colonel Lownds had called off plans for a reinforcement by a company of Marines from the combat base-- with the 256th Regional Force Company airlifted from Quang Tri.

When the helicopters landed with these Vietnamese troops aboard they were ambushed by waiting People's Army soldiers. Over a hundred Vietnamese and Americans died or disappeared, including Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Seymoe, the deputy senior advisor for Quang Tri province. By nightfall, though Clark had held Khe Sanh village, it was clear his entire force stood in grave danger. The following morning the village and outlying hamlets were abandoned. At least two dozen defenders were killed and forty more wounded. Estimates of North Vietnamese battle deaths ran to several hundred.

Aside from supporting Khe Sanh village under attack, on January 21 the Air Force inaugurated Operation NIAGARA, a massive aerial bombardment in the entire Khe Sanh sector. Identified targets were hit, enemy forces spotted were pasted, and interdiction blocked points throughout the area. To develop targets for the bombers, MACV set up a special intelligence staff at its Saigon headquarters, while Khe Sanh Combat Base began using remote sensor techniques originally intended for the McNamara Line. Another MACV staff rerouted ARC LIGHT strikes in flight, providing near-real time targets for the huge B-52s.

Air Effort

The air effort at Khe Sanh would be enormous. The Seventh Air Force flew 9,691 sorties into the NIAGARA area, dropping 14,223 tons of bombs, rockets, and other munitions. The 1st Marine Air Wing flew 7,078 sorties and delivered 17,015 tons of ordnance. From YANKEE STATION the Navy's aircraft carriers contributed another 5,337 sorties that brought 7,951 tons of ordnance. Then there were the ARC LIGHTS.

The B-52s sortie numbers were just 2,548, but they delivered 59,542 tons of bombs. Altogether this was truly the cascade of aerial munitions which General Westmoreland imagined as he reached for a suitable code name for this operation and thought of Niagara Falls. In all almost 1,300 tons of bombs fell around Khe Sanh each day of the siege. Put differently, that was the equivalent of a 1.3 kiloton tactical nuclear weapon every day!

As Major Clark withdrew his survivors from Khe Sanh village on January 22, at the combat base the Marines brought up fresh troops, this time the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines. Having originally arrived in June 1965, 1/9 was among the longest-service U.S. rifle battalions in South Vietnam. It was a 1/9 patrol that had touched off the Hill Fight near Khe Sanh in 1967, and the battalion also had fought hard at Con Thien, another post near the Demilitarized Zone, where an extended battle raged that summer.

Walking Dead

So many times had the unit been in harm's way that its men nicknamed 1/9 the "Walking Dead." Colonel Lownds immediately posted the new unit to a low hill not far from the base that Marines called the Rock Quarry. Five days later the South Vietnamese army sent Khe Sanh its 37th Ranger Battalion, which Lownds used to extend the perimeter near the end of the runway at the main combat base.

Counting the troops of Forward Operating Base (FOB) 3 of MACSOG, who numbered close to 500; the detachment of Marine recon men; the remnants from the village; a unit of Army heavy weapons; and other odds and ends, the defenders of Khe Sanh finally added up to about 600 troops.

It was the night of January 24 that the mettle of the garrison would really be tested. That night the People's Army began using real artillery (as opposed to rockets and mortars) for the first time -- 100mm and 152mm guns.. The Vietnamese bombardment hit both the combat base and the hilltop positions, in this case the strongpoints on Hills 881-South and 861. About 250 artillery rounds fell on the main combat base, fortunately without the effect of The Bombardment.

Shelling after that continued every day, with an exception that will be mentioned shortly. The People's Army took advantage of the fact that its Russian-built 130mm and 152mm guns outranged the Marine weapons, which were 105mm howitzers, 106mm recoilless rifles, and 155mm guns and howitzers. The Marines also had held from some Army artillery, 175mm guns emplaced at Thon Son Lam, in the Vietnamese foothills at the tip of the strongpoint system of the McNamara Line. Those Army guns could just reach Khe Sanh, but not past it, so they too were no good against People's Army gun emplacements far to the west. Hanoi's soldiers carefully placed their cannon where the Americans could not shell them back, but where they could comfortably reach Khe Sanh and its hills.

That first artillery barrage once again covered a People's Army maneuver. On the night of January 23/24 a full regiment of People's Army troops backed by tanks-the first use of armor In an assault role by Hanoi in the Vietnam war -- attacked a Laotian outpost called Ban Houei Sane. Just across the border, that post covered the approaches to Lang Vei Special Forces Camp. The 33rd Volunteer Infantry Battalion, the Laotian garrison, proved no match for the People's Army. About fifty Lao were captured, over a hundred killed or missing, and the remaining soldiers and their families fled in the only direction possible -- across the Vietnamese border and into Lang Vei village, where they would later be swept up in the flood of civilians trying to escape the battles in the Khe Sanh area.

Artillery

The exception to the new daily pattern and its constant stream of shells to harass the Americans and South Vietnamese troops would be the day of Ter. Where the rest of South Vietnam boiled over in a contagion of fighting, Khe Sanh remained quiet. There were no attacks.

There was even an episode in which the People's Army broke into the radio net of the South Vietnamese 37th Rangers, who were conducting a patrol, and requested them to observe a ceasefire and return to their lines, remarking that the patrol was being tracked and could be fired upon. Hanoi's troops held their fire even though the Rangers went on with the probe. The most that happened at Khe Sanh on Tertwould be someone's loosing a half dozen rounds of light (60mm) mortar fire. Real battle began only a week later.

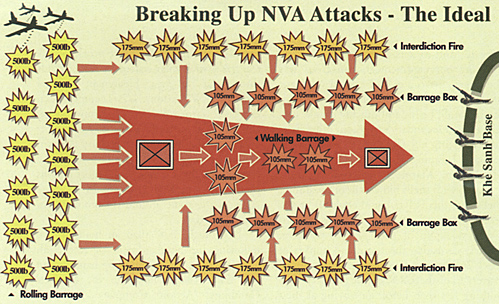

Breaking Up NVA Attacks

Vietnam Climax Siege of Khe Sanh

- Introduction

Approach to Battle

Contact

The Siege

Opening the Road to Khe Sanh

Map: North Vietnam's Plan of Attack (slow: 155K)

Map: Khe Sanh Village (slow: 140K)

Map: Khe Sanh Combat Base Layout (very slow: 247K)

Intelligence and Battles

Charlie Knocks: We Drop

Khe Sanh in Wargames

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.